Has digitisation destroyed our ability to read long and complicated texts?

Experts disagree about whether something has happened to our ability to read for a long time. In any case, it is entirely possible to learn to improve your concentration, says one researcher.

More and more people are concerned about our ability to read at length. Are we going to stop talking to each other in favour of communicating through a digital medium? Has the flood of digital information weakened our judgement?

Has digitization destroyed our ability to read at length?

We asked reading researcher Anne Mangen and psychology professor Lin Sørensen what they think.

The end of long reading?

In an article published on forskning.no (link in Norwegian) earlier this year, professor emeritus Ivar Bråten at the Department of Education at the University of Oslo said that ‘it is possible that we are seeing the beginning of the end of long reading as we know it.’

Professors Espen Ytreberg and Arne Johan Vetlesen, both associated with the University of Oslo, claimed early this year in articles in two Norwegian newspapers, Morgenbladet and Klassekampen, that today's students lack the ability to read longer, complicated texts.

But what does the research say? Have we really become worse at reading than we were before? And is it really that important to be able to concentrate without being distracted, in order to understand what we read?

Stable development

The reading skills of Norwegian 15-year-olds are surveyed at regular intervals in an international study called PISA (link in Norwegian). The results from the PISA survey carried out in 2018 have been regularly referred to in the debate on digitization and reading skills.

In a summary of the results from the PISA surveys from 2000 to 2018, it appears that Norwegian pupils’ reading skills have remained stable during the period. However, the international average has decreased.

The authors of the summary point out that Norwegian pupils have had consistently high reading achievements throughout a period when society and texting culture have undergone major changes.

Less leisure reading

What the PISA summary shows is that Norwegian pupils’ reading habits and attitudes towards reading have changed.

Pupils read less in their free time than they did in 2000, and they read long texts less often.

At the same time, online reading has increased.

It appears that students who answer that they chat with others several times a day score better than other students on the reading test. The same applies to those who more often than others search for information online or read online newspapers.

Complex challenge

Anne Mangen is a reading researcher and professor at the University of Stavanger. She has studied the effect of the medium on reading comprehension and the difference between reading on paper and on a screen.

When asked whether there is research that shows that we have become worse at reading at length, Mangen says the answer depends on how we measure reading.

“The PISA results are an indication when it comes to 15-year-olds, and the results in 2018 showed a decline in reading compared to 2015. But we must remember that PISA is one way of measuring reading skills and habits. There are many facets of reading that are not captured in a survey like this, such as endurance in reading and the ability to read long and complex texts,” she said to sciencenorway.no.

Pupils, teenagers and adults themselves report that they are reading fewer books and long texts.

Instead, there are other indicators that tell us that we have become worse at reading, including experiences from teachers, professors and ourselves.

“These days we read short snippets here and there, and have less training in what it is like to spend time with the same text over a longer period. Pupils, teenagers and adults themselves report that they are reading fewer books and long texts. Teachers have also reported this,” says Mangen.

She says that the ability to read long, coherent and more complex texts is a multi faceted challenge.

“One thing is the differences between reading long, complex texts on paper and on a screen. But then there are also distractions, meaning the way the entire media landscape has changed so dramatically during such a short time. We have to deal with enormous amounts of information and text at all times, and most of it is immediately available,” she says.

Many say that these changes are particularly noticeable when it comes to reading longer texts.

Reading long texts in spurts

Mangen has recently carried out a reading experiment in conjunction with Ståle Wiig, a social anthropologist at the University of Oslo. The experiment involved asking a group of students to sit quietly and read in a room for five hours, without access to mobile phones. The experiment was discussed in an article on forskning.no (link in Norwegian) earlier this year.

Mangen thinks that these kinds of in-depth reading seminars can be a way to improve students' ability to concentrate when it comes to reading longer, more complex texts.

She says that more time should be set aside for reading at length in school, especially because we read less in our spare time.

“Parents may read less texts to children, perhaps because they themselves read less. So schools and universities have to set aside more time for this,” she says.

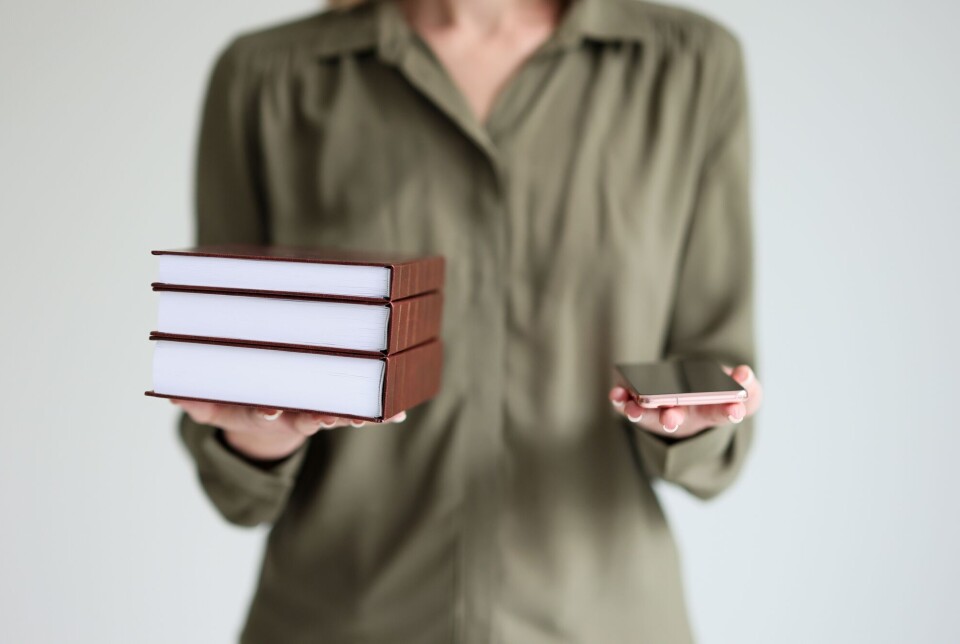

Smartphones not compatible with reading long texts

Mangen also says that people should read longer texts in a paper format.

“I’m not saying that you should never use a screen to read, but you have to aim for balance, where you choose printed and digital media based on what is most appropriate in relation to the type of text, reading purpose and so on. It’s important to keep in mind that the type of training you get from reading a connected text on physical paper has transfer value to digital and digital reading, but the opposite is not true,” she says.

Mangen say that when reading is digital, the reading of longer and complex texts will come to a screeching halt. She explains that this means that people will get less practice reading longer texts, in part because much of the reading we do is on our smartphones.

A smartphone “is small and not very compatible for reading long, academic texts, for example. Both because it makes us vulnerable to distractions and because of the materiality. After all, reading is multisensory, and not something we only do with our eyes and brain,” she says.

External expectations

We like to think it’s important to concentrate when we read. But what do we really mean when we talk about concentration? Psychology professor Lin Sørensen explains that the term can have several different meanings in academic language. This is why researchers often talk about attention.

“But when we talk about whether someone is better or worse at concentrating, it is more about what is expected externally, and that you are able to adapt to what is expected by teachers, parents or at work,” says Sørensen.

“What is challenging is being able to manage one's concentration. It is much easier to concentrate on something we want to do,” she said.

Negative focus

Lin Sørensen says that she is critical of the negative perception of the use of mobile phones and apps.

“It has almost become immoral for people to use apps. We should rather read books— and the poor people who are young today, what will happen with them?” she said.

Sørensen says she thinks things will be fine with young people today.

“Things change all the time. New things come, positive things, but they can also present challenges,” she said.

Comparing reading and training

Has digitization led to us having poor concentration skills? Sørensen doesn’t think so.

“I don’t conduct research on this, so I can’t speak from a research perspective. But I think that if this had been true, we would have seen that students had become worse at school,” she said.

Sørensen instead believes that we are distracted by different things now than previously. She compares diving into text, especially one linked to studies or other topics for which you’re not that motivated, to working out.

“It's hard to get started — just like getting out the door when you're training,” she said.

Possible to improve concentration

The comparison between reading and training opens the door on the question of whether it is possible to train our ability to concentrate.

Sørensen explains that it is entirely possible to train for better concentration.

“The research literature raises the idea that going to school in itself can be considered a form of attention training. We are actually trained to function in our society,” she said.

She explains that whether our ability to concentrate is considered good or bad depends on societal expectations.

“And it’s clear that there are high requirements for concentration. Many people have years of education, and many jobs are knowledge-based and require concentration,” Sørensen said.

Should we try to concentrate without being distracted?

Sørensen believes that distractions are a completely normal part of life and that it is not normal to do difficult work, such as reading research articles or writing reports, without being distracted.

“As long as your concentration is normal, you will be able to return to what you are doing after you have been distracted,” she said.

Sørensen believes the most important thing is that you get what you need from your reading. She adds that choosing which information is most important is also an aspect of concentration.

“You don’t necessarily have to retain everything that is written in a research article,” she said.

Sørensen emphasizes that she doesn’t have research findings on this, but she believes that our concentration skills at school or work haven’t deteriorated, even if it feels easier to watch a film or scroll on social media than to read a book in our spare time.

No need to panic

Has digitization destroyed our ability to read at length? It seems as if learned people disagree.

The PISA survey shows that young people read less in their free time. Nevertheless, reading skills have stayed at a stable level. This may be because we read in different ways than what we have traditionally thought of as reading. For example, many people read news online instead of on paper.

We report that we find it difficult to concentrate on reading long texts. But the fact that we experience reading as difficult does not have to mean that we do not absorb the content of the material we’re reading.

The researchers are optimistic. Both reading researcher Anne Mangen and psychology professor Lin Sørensen agree that it is possible to improve our concentration. The lack of research in the field also shows that there is a need for more research on reading at length in the age of digitalization.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no