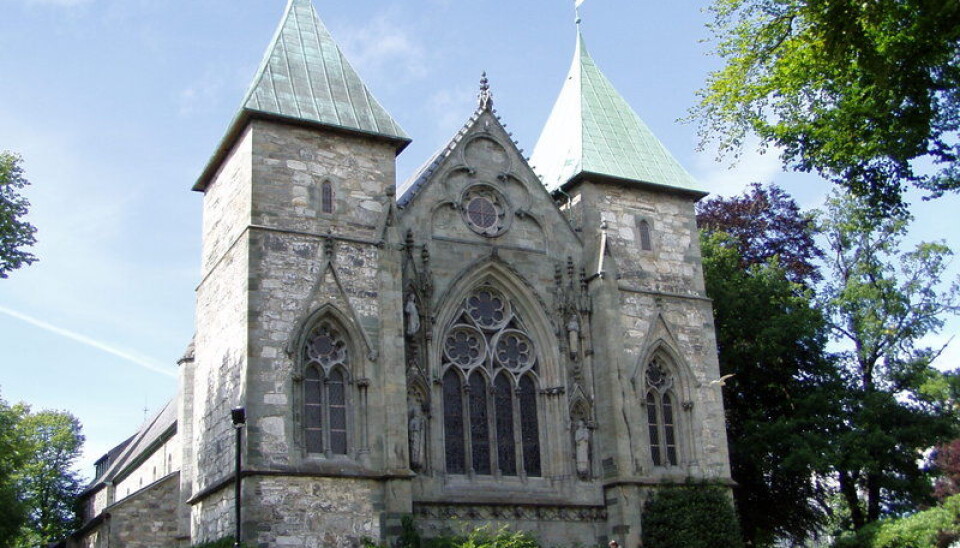

The Christians beneath the cathedral

The Norwegian city Stavanger’s known history commences with the building of its cathedral nearly 900 years ago. Recent analyses of skeletons indicate that several generations of Christians lived there prior to that.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

In historical accounts the history of Stavanger, Norway's third largest city, starts around 1125, when construction work on the city’s cathedral commenced. No findings have indicated any urban centre pre-dating the church.

But a number of skeletons uncovered beneath the cathedral in 1968 indicate that several generations of Christians lived in Stavanger before the cathedral was erected.

Preliminary studies of these human remains indicate that they stem from young children as well as adults.

A total of 31 skeletons were found beneath the cathedral. In the late 1960s the only place in Norway that could house such discoveries was the Department of Anatomy at the University of Oslo.

Around 1970 the bones were returned to Stavanger but they were in rather poor condition. They had all been jumbled together into one large crate. Efforts started last year to reassemble them.

From the year 1000

Sean Dexter Denham is an osteoarchaeologist at the Museum of Archaeology in Stavanger. He’s an expert at identifying skeletal remains and is systematically working his way through the large crate and assembling the bones into complete skeletons.

“We know that at least 20 skeletons were returned to us from Oslo, but we don’t really know whether we have bones from all 31.”

He is studying the cathedral skeletons with the help of techniques that have also been used in work at sites of mass graves in Iraq and the former Yugoslavia.

Samples have been sent off for both C-14 and AMS radiocarbon dating, and these show that the skeletons are from the late Viking era and early Middle Ages, or around the year 1000.

Unfortunately the dating methods are not accurate enough to establish an exact year, but as more and more samples are taken the easier it is to estimate the age of the bones, and Denham is planning to do just that.

“We know the skeletons are older than the cathedral, but we don’t know exactly how much older. This is a big question. It’s a matter of who it was who lived here in this city."

Conducting DNA analyses

Paula Utigard Sandvik is an associate professor and biologist at the museum and she is working with Denham on the skeletons and the rest of the finds buried beneath the cathedral.

She praises the report made when the skeletons were found in 1968. The report and later studies confirm that the corpses had been placed in coffins and buried.

The corpses were lined along a perfect east-west axis, they had not been burned and no funerary relics have been found in their vicinity. Everything points toward Christian funerals.

Sandvik says it is odd that such a fine building was erected without evidence of it being pre-dated by an urban Christian settlement.

“In other Norwegian medieval towns we find traces of urban regulation, street structures and remains of houses. According to the way they were organised we can determine whether the site was a town or a large farm complex. Such evidence is almost totally lacking for Stavanger prior to around the year 1000."

She says that construction of cathedrals was often politically motivated and that the Stavanger Cathedral could have been erected when the already married Sigurd the Crusader couldn’t persuade any bishops to wed him to his second wife.

Sigurd I Magnusson Jorsalfare, as he is known in Norwegian, was king of Norway from 1123 until his death in Oslo in 1130.

“In the Catholic Church it was inconceivable to be divorced and have two wives but he attempted to get Norwegian bishops to bend the rules. He found one who was willing in Stavanger but it cost him a tidy sum that was sufficient to start the building of the cathedral. Jorsalfare got his new wife, and Stavanger became a cathedral city."

Sandvik says she is in the process of starting isotope analyses of the skeletons to see whether they shared a common diet, and hopefully conduct DNA analyses to find out if they were related.

Sandvik and Denham haven’t published any of their studies of the skeletons but both say they have several studies planned.

“We know so little”

Geir Atle Ersland is an associate professor in history at the University of Bergen who is currently working on the first volume of a new edition of Stavanger’s history, which starts around the time of the cathedral construction.

“We know nearly nothing about Stavanger’s history prior to the start of construction, and apart from archaeological finds there is nothing to help us out.”

In addition to the skeletons, a few postholes, a layer of charcoal and a stone cross are among the most important finds providing a look into this puzzling period.

The cross, which used to stand a little distance from the cathedral, is now considered to be the country’s oldest historic national monument, and was placed in memory of Erling Skjalgsson.

The chieftain Skjalgsson was one of decentralized Norway’s most powerful men around the first millennium.

Many historians think the placement of the memorial cross indicates that there was a town or community where Stavanger is now.

But the cross has been in a museum since the 1800s and even though it was found in the middle of Stavanger, researchers cannot say for certain whether this is where it originally stood.

“The first time the stone cross was mentioned in written sources was in 1726. Another concern is that it’s hard to make any direct correlations between the cross and the construction of the cathedral.”

Not necessarily a settlement

Ersland says that the history of Sigurd Jorsalfare, who was born 60 years after the death of Skjalgsson, is reasonably well established.

The writings of Snorre Sturlasson about Jorsalfare match nicely with the constructional archaeological evidence, but apart from Heimskringla, written documents about Stavanger prior the 1200s are lacking.

“But a lack of written sources doesn’t mean nobody was living there. The Christian burials indicate that there could have been a church at the site or nearby. On the other hand, in the 11th century a lot of churches were built in Norway without necessarily being located in populated settlements.”

Ersland says we have to accept the compelling knowledge that there were Christian burials and probably a Christian cult site in Stavanger before the cathedral was built, but we cannot know in what context.

“But questions without answers tend to be the most intriguing ones; the air goes out of the balloon as soon as an answer if found. That’s why this question will always be of interest. Stavanger’s origins might never emerge from the shadows of history,” concludes Ersland.

___________________________________

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Related content