Share your science:

Why did the population in Southern Norway decline dramatically after the 6th century?

SHARE YOUR SCIENCE: The decline in population tells us something important about Scandinavia during the Iron Age.

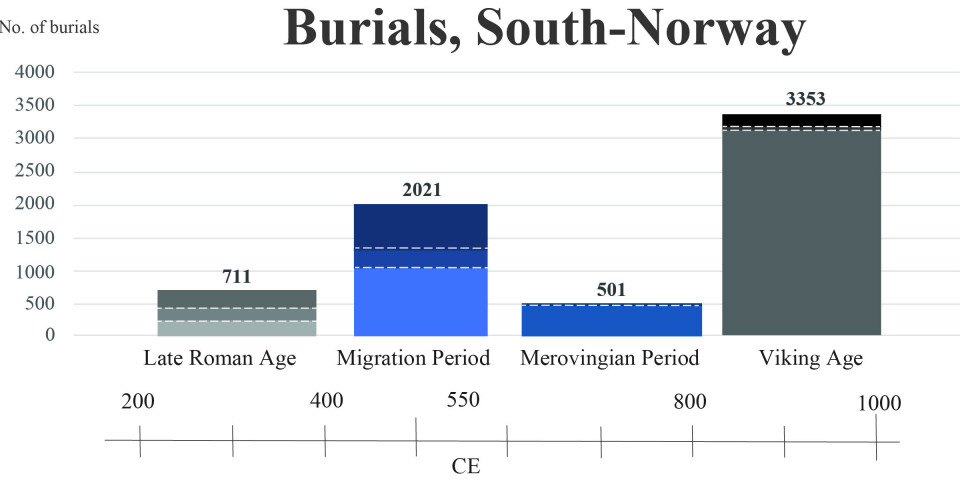

Analysis of nearly 7,000 dated burials indicates a significant population decline in South Norway following the 6th century, with the number of burials dropping by over 75 per cent compared with the preceding period.

This demographic downturn, tied to environmental and societal crises, provides critical insight into Iron Age Scandinavia’s cultural and population dynamics.

Even modest disruptions can trigger major societal changes in fragile systems

While burials do not equate directly to population size, they offer valuable insights into societal trends and disruptions. Notably, the sharp decline in burials post-6th century coincides with other archaeological indicators, such as reduced settlement activity and a decline in radiocarbon dates, suggesting a significant population downturn.

The 6th Century Crisis: Causes and Effects

In a recent paper we argue that this decline is linked to a combination of climatic and epidemiological factors. Two major volcanic eruptions in 536 and 540 CE triggered a prolonged cooling period that may have caused widespread crop failures and famines.

Simultaneously, the first bubonic plague pandemic emerged, potentially reaching Scandinavia or indirectly affecting it through disrupted trade and societal instability. These crises occurred in a society already vulnerable due to population pressures and resource strain following a period of agricultural expansion.

Before the 6th century, South Norway experienced agricultural and population growth. However, this growth stretched regional resources, leaving communities vulnerable to external shocks.

The volcanic eruptions and resulting climate crisis likely catalysed existing instabilities, reducing crop yields and exacerbating societal pressures. The consequences varied regionally, with some areas faring better than others.

Even modest disruptions can trigger major societal changes in fragile systems. The 6th century crises appear to have disrupted settlement patterns, rituals, and cultural practices. For example, changes in burial traditions and fewer material-rich graves reflect shifting societal structures and values.

Shocks and social dynamics

The 6th and 7th centuries saw fewer, less elaborate burials alongside the construction of monumental mounds such as the single massive mounds of Raknehaugen or Jellhaugen, or the concentrations of larger mounds at Borre or Gamle Uppsala.

These developments suggest significant socio-economic transformations. The elite may have used grand mounds to assert power amidst crises, consolidating influence in a time of social unrest.

While devastating, the mid-6th century crisis may have sown the seeds for future recovery and innovation.

Conversely, fewer rich burials, such as is the case in the 7th century, may be indicative of an elite that had established themselves as a stable power factor, taking advantage of the crisis as a catalyst for social stratification and increasing their influence and power.

However, if few burials are indicative of a more hierarchical society in the 6th and 7th centuries, with fewer free men/landlords, how are we to interpret the rich periods before and after?

Research from the better documented Black Death of the 14th century suggests that, for most of society, sudden crises can act as violent shocks that disrupt the established order and initiate social and economic equalisation. For the majority of those who survived the plague, the late Middle Ages were a time of relative prosperity.

Perhaps the fewer and less conspicuous burials after the 6th century should be seen in this light. For those who made it through the 6th century, the socially equalised 7th century society may have opened up new opportunities during a brief period in which society may have been more egalitarian and resources more evenly distributed—perhaps similar to the initial consequences of the Black Death.

This may also offer an alternative interpretation of the monumental yet scarcely furnished mounds of the period. They may not be manifestations of an increased hierarchical society, but collective actions and rituals, perhaps to propitiate the spirits; a rational solution to the extraordinary events of the mid-6th century may thus have been extraordinary rituals.

At the same time, there are several indications of increased concentrations of power during the 6th and 7th centuries, evidenced by elite residences such as Åker, Borre, Gamla Uppsala, Lejre, and Tissø. This apparent contradiction might be explained by a smaller elite consolidating more control.

While many elites likely struggled to maintain their positions amidst a shrinking labour force and political unrest, some may have gained more power at the expense of their former contemporaries.

This shift in the social structure of Scandinavia, where the higher social strata diminished in numbers, may also be mirrored regarding the lower strata, resulting in the emergence of a larger so-called ‘middle class’, perhaps exemplified by an emerging uniformity in clothing and jewelry aesthetics during the 7th and 8th centuries.

The period also illustrates the interplay between environmental challenges and societal resilience. While devastating, the mid-6th century crisis may have sown the seeds for future recovery and innovation.

By the Viking Age, South Norway saw a resurgence in population, driven by favourable climatic conditions, advanced agriculture, and expanding trade networks.

Further reading:

Share your science or have an opinion in the Researchers' zone

The ScienceNorway Researchers' zone consists of opinions, blogs and popular science pieces written by researchers and scientists from or based in Norway.

Want to contribute? Send us an email!