No, you don't have a reptilian brain inside your brain

The myth of the reptilian brain is tenacious – but wrong.

The reptilian brain is often blamed for our primitive instincts that can trigger fight, flight or freeze responses in us.

However, it is a myth that part of our brain originates from reptiles, says Christian Krog Tamnes.

“Those of us who research brain development and brain evolution have known for quite some time that this isn’t true,” says the professor at the University of Oslo’s Department of Psychology.

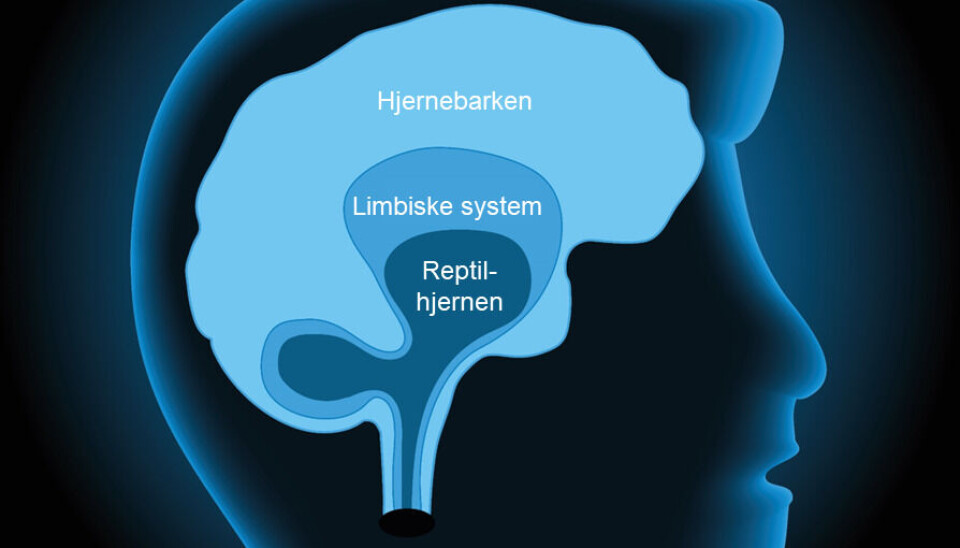

The triune brain

The concept of a reptilian brain is part of the myth of the triune brain, a theory that was conceived by the doctor Paul D. MacLean in the 1960s.

Carl Sagan popularized this way of thinking in his book The Dragons of Eden, published in 1977.

MacLean's idea was that our brain has evolved layer by layer.

The reptilian brain was considered to be the innermost and oldest part. This primitive brain was responsible for instincts like hunger, survival and mating.

The emotion-controlled limbic system was said to wrap around the reptilian brain, and the surrounding outermost layer was the rational neo-cortex.

Seemingly simple explanation

Two things are wrong about this theory, says Tamnes.

First, the brain did not develop this way through evolution.

Second, instincts, emotions and reason don’t exist in separate parts of the brain, he says.

Nevertheless, the myth is alive and well. Tamnes thinks that may be because brain research sounds so convincing.

“This theory provides a seemingly simple explanation for complex things, which is appealing,” he says.

Examined reptilian brains to understand evolution

A 2022 study in the scientific journal Science put another nail in the coffin regarding the myth of a reptilian brain deep inside our brain.

The researchers studied brain cells from the bearded lizard.

They wanted to find out if they could detect common features between the brains of reptiles and mammals.

To that end, they compared the brain cells of lizards and mice.

Spread throughout the brain

And the researchers found some similarities. They write that the cells, which are similar to each other, may originate from our common ancestors 320 million years ago.

But these stem cells were not collected from one place in the lizard brain or the mouse brain.

Instead, the cells that are similar to each other were found scattered throughout the brains of both species.

“This finding challenges the idea that some brain regions are older than others,” the researchers write in their article.

Brain has developed in parallel

The finding agrees with previous research on brain evolution.

Humans and other animals living now have common ancestors, but they have evolved in parallel from a common attribute.

Advanced brains and nervous systems have evolved independently many times. American researchers have confirmed this in an article that shatters the myth of the reptilian brain in the scientific journal Current Directions in Psychological Science.

“The idea that the old structures have been preserved unchanged through evolution is wrong,” says Tamnes.

Even though several animals living now may have a similar brain structure, the different parts have continued to evolve independently within each species.

Gross oversimplification

On to point number two: The idea that each part of the brain is responsible for certain things does not agree with modern brain research.

“To say that one part of the brain has this function and another part has that function is a gross oversimplification and is at best only true for simple and specific functions,” says Tamnes.

The truth is much more complicated.

Fear is not created in one place in the brain

Lisa Feldman Barrett, a professor at Northeastern University, is one of the neuroscientists who has shown that fear does not arise in only one place in the brain.

Other researchers have investigated where emotions are found in the brain with the help of brain scans. Barrett and her colleagues have pooled all these studies.

They made a startling discovery:

Emotions, such as fear and sadness, are not made in one specific place in the brain. In fact, several parts of the brain are always involved.

Which parts of the brain are active vary from time to time, and from person to person.

More like an orchestra

The idea that the rational neo-cortex fights against the more primitive parts of the brain is also wrong, according to the American researcher.

“The brain is not a battlefield between reason and emotion,” Barrett said in a lecture at The University of Waikato in 2020.

This is why she wants the myth of the reptilian brain to go away.

Tamnes believes that even when the triune brain concept is only used as a metaphor, it should be scrapped.

“I think that we have to try to convey knowledge about the brain that is correct.”

“So if we absolutely need to have a metaphor, it’s much better to think of the brain as an orchestra. Even playing a simple song requires a lot of pieces to talk together effectively and in a coordinated way,” says the neuroscientist.

Translated by: Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

David Hain et al: Molecular diversity and evolution of neuron types in the amniote brain, Science, September 2022. Summary.

Joseph Cesario and others: Your Brain Is Not an Onion With a Tiny Reptile Inside, Current Directions in Psychological Science, May 2020.

Lecture by Lisa Feldman Barrett: How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain, The University of Waikato, 13 October 2020 YouTube.