100 years ago, all Norwegians had to get surnames

It made it easier to keep track of people.

Have you ever thought about why you have the name you do?

You may be named after someone, or perhaps your parents thought the name sounded nice?

Researchers believe that first names have existed for as long as we have used language. That could be as long as 100,000 years.

Surnames, however, are a different matter.

Everyone must have a surname

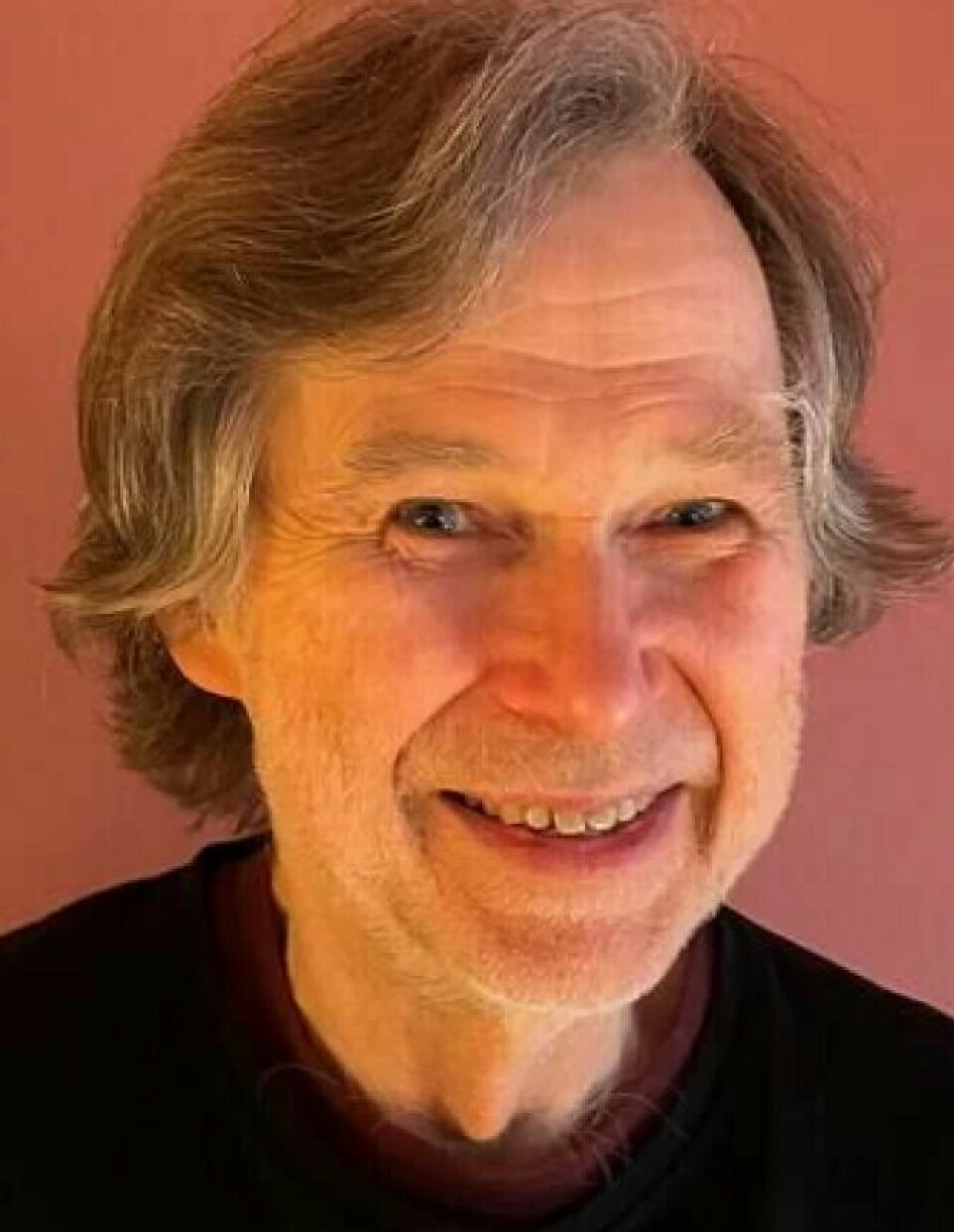

“This year marks 100 years since everyone had to get a surname in Norway,” Ivar Utne says. He is an associate professor at the University of Bergen, and is interested in names.

Before that, surnames had been somewhat trendy and optional.

“The Personal Names Act came in 1923. From that point onwards, everyone was to have fixed surnames in their families. If new children were born, they were to be given the same name,” Utne says.

“Why did people have to have surnames?”

“So that it was possible to keep track of who was who,” he says.

It was convenient for tax payments, hospitals, and schooling.

“The more organised our country became, the better overview there had to be of our inhabitants,” Utne says.

-sen

Before the Personal Names Act, girls were given their father's first name with the word -datter (daughter in Norwegian) added to the end of it as their surname.

If the father was called Hans, his daughter could be named Anna Hansdatter.

“With the Personal Names Act, it became common to take the father's name, and then put -sen at the end. It applied to everyone in the family,” Utne says.

If the father’s first name was Ole, they became the Olsen or Olesen family.

Of the 30 most common surnames in Norway, 23 of them end in sen. Hansen, Johansen and Olsen are most common.

The rest of the names on the list come from farm names such as Berg, Haugen and Dahl.

Came from abroad

Surnames came to Norway from other countries first in the 17th and 18th centuries.

“Some brought names with them from countries such as Germany and Denmark. Surnames were mostly used in the cities,” Utne says.

Around the 19th century, people began to move from the countryside to the cities. More people also started using surnames then.

Some of the foreign names came from occupations. Smith comes from blacksmith, and Møller comes from someone who grinds grain into flour with a mill.

Other surnames came from nicknames, such as Lange.

You can create your own surname

If you want to change your surname, you must apply for permission first.

“You can choose any name that more than 200 people have. If 200 or fewer people have that surname, then you must get permission from everyone with the same name,” Utne says.

You can also invent your very own.

“The comedian Espen Thoresen did that. He changed his name to Espen Thoresen Hværsaagod-Takkskalduha,” Utne says.

Hværsaagod-Takkskalduha is essentially the Norwegian for ‘you’re welcome-thank you’ but is spelt slightly differently.

Utne has also heard of someone who changed their surname to Eplet (the apple) and Æljen (the moose).

“There are many possibilities,” he says.

Ask your family

Utne constantly asks people where their surnames come from.

“There are a surprising number of people who don't know,” he says.

If you are unsure, Utne recommends that you ask your family. There are also ‘name books’ that can help.

“If people are called Andersen, there must be an Anders somewhere in the family’s history. If the surname is a place name, it must be from a farm,” he says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on ung.forskning.no

------