New Norwegian population registry simplifies genealogical research

Parish registries, obituaries and prison records are some of the sources for a new historical population registry. The general population can access their ancestors, but only researchers have access to sensitive health information.

Researchers will now be able to immerse themselves in information about deceased Norwegians to find answers to historical, medical and social science puzzles.

The spread of diseases, changes in child mortality, and social and geographical mobility are just some of the information the registry can provide an overview of, according to a recent NRK Dagsnytt report (in Norwegian).

Censuses, parish registries and emigration records are among the sources used so far to compile an overview of Norwegian ancestors' lives reaching back to 1800.

During the period 1800 to 1964, 9.2 million people lived in Norway. The goal is to eventually have all deceased Norwegians entered in the register.

Free access for all

Access to searching for relatives or dead celebrities in the open registry is free for anyone via the website histreg.no (an English presentation is available), greatly simplifying research for hobby genealogists. We can obtain instant answers to when our ancestors were baptized, confirmed, married and died.

But you may not find all your deceased grandparents or other relatives in the registry. For example, the journalist for this article found only one grandfather, Paul Anton Stranden, who was born in 1903. He married 21-year-old Anna Margrete Sandvik. No children are registered although they had two children, a boy and a girl.

“So far all Norwegians born before the census in 1910 are in the registry. After this date, the number of people entered varies by location,” says Lars Holden, managing director of the Norwegian Computing Center and among those responsible for the registry.

Small parishes have the best records

The Aftenposten newspaper’s obituaries between 1950 and 2000 have also been added.

“We’ve only managed to read half the obituaries in the newspaper. They’re mostly limited to people from Oslo and Akershus,” says Holden.

Avid local historians have been more frequent contributors to the digitization of old parish registries from small church parishes in rural Norway in the Norwegian National Archives.

“Big cities and more central districts are a bit behind when it comes to digitizing parish registries,” says Holden.

During fall 2019, the researchers will post the official list of people who died between 1951 and 2017.

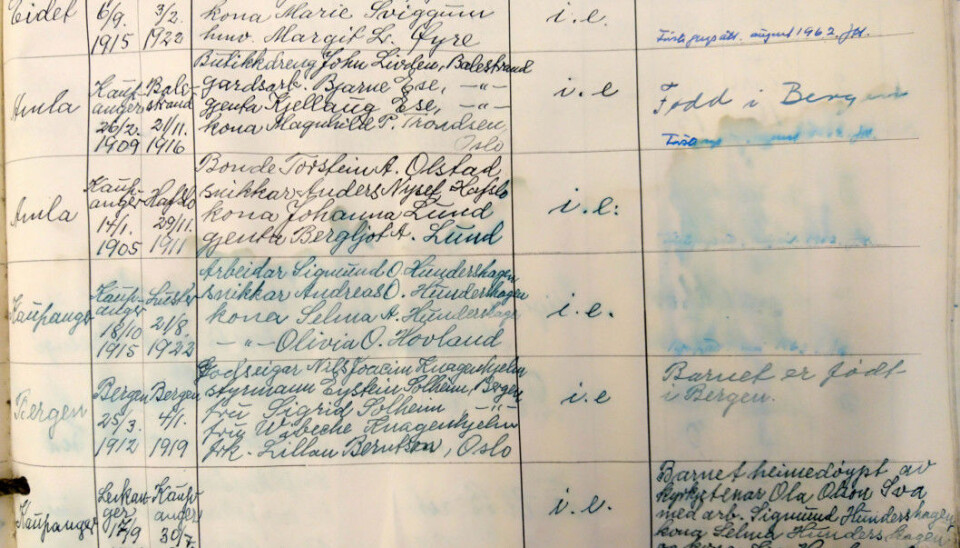

Handwriting recognition software

Deciphering the handwriting in old documents is a challenge. The Norwegian Computing Center transcribes handwriting using artificial intelligence.

“We have 50 mathematicians and statisticians working with data analysis and artificial intelligence,” says Holden.

“We use handwriting recognition software. This means that interpreting names and dates goes much faster than before,” he adds.

Programs like this used to recognize only single letters and numbers, whereas they now take in entire words, names and number rows at a time.

Information about a person and their close family members is linked. The hope is to follow the population for six to seven generations.

Health information reserved for researchers

In addition, health records provide a picture of how mental and physical illnesses have travelled.

“Researchers have revealed that a hereditary form of breast cancer, which was widespread in Rogaland county, spread to Lofoten through fishermen who went there,” says Holden.

Sensitive medical information about Norwegian parents and ancestors will only be available to researchers upon application for specific research purposes,” says Holden.

Applications will first require approval from the ethics committees.

Statistics Norway, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and other institutions that have this data supply this limited-access information.

The historical registry only provides names, relationships and other open-access information that they receive, such as from parish registries.

To the question as to whether the general public will be able to dig up a neighbour’s health information, Holden assures us that these registers are closed to private individuals.

Invited to volunteer

International researchers are showing a strong interest in the new registry, because other countries are not as far along in compiling such records.

“So far we have 50 different affiliated research groups, of which one third are from abroad,” Holden says.

Norway has made more headway in gathering information about all deceased inhabitants into one central location.

“We’re also ahead of Denmark and Sweden,” says Holden.

In addition to the mechanical transcription of old church records and censuses, 90 volunteer genealogists and local historians are also contributing their time.

“The volunteers can link information and add to what they know about family relationships,” says Holden. “To date, they’ve connected 5.8 million bits of information about individuals mentioned in the registries.”

Privacy

Living individuals are not entered into the registry for privacy reasons.

"Our practices are stricter than the Norwegian Data Protection Authority recommends for genealogical research," Holden says.

The Norwegian Computing Center has been working on the registry for six years. They are responsible for developing the histreg.no website and the database behind it. UiT-Norway's Arctic University is managing the historical population registry project with several partners: the National Archives of Norway, Statistics Norway, the Norwegian Computing Center and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The Research Council of Norway is financing the project.

A lot of work still remains.

“We also have some funding from other sources. The registry is important to so many researchers and other users that I feel confident we can complete it. But with more funding, we can create a good registry faster,” Holden says.

————