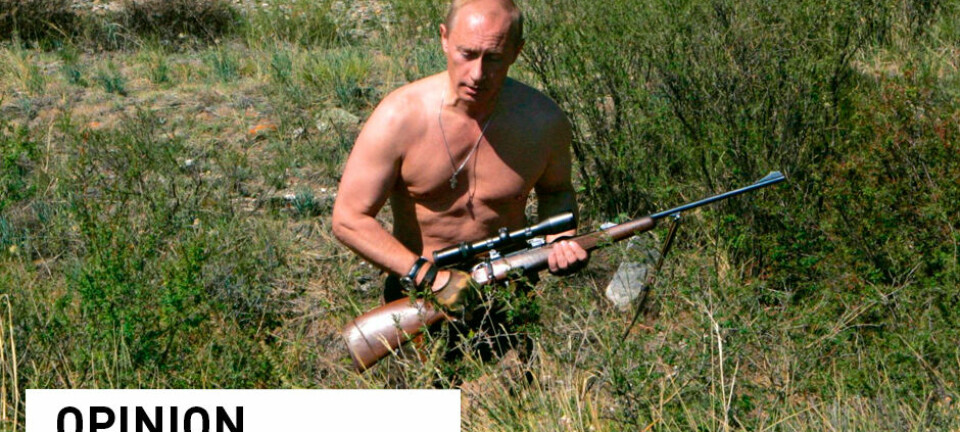

Do Putin’s religion and homophobia tactics rally support for him?

Researchers conducting an international research project at the University of Oslo are far from convinced.

Over the past decade, the Putin regime has increasingly based the support it seeks from Russians on traditional Russian values.

Orthodox Russian Christianity has become part of Putin's politics.

At the same time, the regime has stepped up its attacks on homosexuals and others who violate traditional Russian norms for gender and sexuality.

“But the fact that Putin believes this to be to his advantage doesn’t necessarily mean that it is,” says Henry Hale, a political science professor at George Washington University.

He recently gave a lecture at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI). Hale is participating in the LegitRuss research project at the University of Oslo.

Unique survey

Although quite a few Russians see Putin as a moral authority, the LegitRuss researchers have found little to indicate that the Russian president wins any significant support for his statements about religion and sexual minorities.

The researchers base their findings partially on a unique survey that the project carried out in Russia in 2021 with funding from the Research Council of Norway. The survey was conducted shortly before the Russian attack on Ukraine.

It seems religion and homophobia might therefore not be an effective legitimation strategy for Putin and his regime.

The survey in Russia

The survey that the researchers in the LegitRuss project were able to carry out in 2021 included a sample of 1 500 Russians.

“I think this survey gives us a fairly unique insight into connections between traditional values and support for Putin. It goes deeper and is more nuanced than previous investigations,” says Hale.

“When it comes to sexuality, we find an enormous amount of intolerance among Russians. Fully 89 per cent say that marriage is something that can only be entered into between a man and a woman. And 69 per cent say that they don’t want people from a sexual minority as neighbours.”

“Nevertheless,” he says, “less than a third of the population responded that they follow Putin’s opinions on sexual orientation and religion.”

So, Hale wondered, does it work for the Kremlin when Putin talks about these topics?

In general, he thinks Putin has little to gain from his rhetoric about religion and sexual minorities. It’s more likely that his utterances put him in danger of losing support.

Putin loses on religion and homophobia

When Putin talks about religion, he loses ground among more secular Russians.

At the same time, the researchers find that he does not necessarily win support among the more conservative religious group, who tend to be women.

“Putin’s support in Russia is much broader than just the conservatives. With his rhetoric, he often has more to lose among liberal Russians than he has to gain among conservatives,” Hale said.

Putin not supported by homophobes

The researchers have found that people who can be put in the conservative category are very likely to vote for Putin in an election.

But at the same time, the researchers found that people who can be placed in the homophobic category are less supportive of Putin.

The same applies to people with higher levels of education – and people who are poor.

All told, the researchers note that trying to build legitimacy and support for traditional Russian values related to religion and sexuality could be a minefield to move into for an authoritarian leader like Vladimir Putin.

This is risky business for him.

Fear of chaos

How Russian adults remember the chaotic 1990s has a lot to do with why so many Russians still support Putin.

In this arena, Putin has been able to profile himself as a kind of guarantor of anti-chaos.

The Putin regime uses a narrative about how the West tried to exploit the Russians when the country was on its back, which helps to give him a lot of support.

Part of the picture is also that Putin has a leadership style that probably appeals to many Russians.

Are the polls right?

Hale believes the opinion polls in Russia that show strong support for Putin probably greatly exaggerate the actual support he has.

“But they’re not completely wrong,” he says.

The American political science professor believes that support for Putin and what he is doing in Russia could probably continue for a while, but only until it becomes impossible for Putin and his regime to escape the facts about how the war in Ukraine is really going.

Something might turn when even more men come home in body bags and the Russian economy really begins to feel the effects of the war.

“I don't see much right now suggesting that the Putin regime will fall. The discontent among more liberal and more pro-business groups around the Kremlin regime is strong. But there are no signs that they’re trying to organize a coup or anything like that,” Hale says.

“Going forward, a lot will depend on how the war progresses. If the Ukrainians manage to push back the Russians, and events are going in the direction of the Ukrainians winning the war, then a lot could happen,” says the professor.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------