Why did Southern and Western Norway become the country’s Bible Belt?

Several countries have their Bible Belts. Researchers have been looking to explain why Christian revivalism became so popular in southern and western Norway.

The years from about 1870 until the 1970s were the period of Norway’s major popular movements.

But these movements received quite different levels of support.

Southern Norway and Western Norway became the main areas of the Christian revival movement and the abstinence movement.

The labour movement gained the strongest support in Eastern Norway and in Trøndelag in mid-Norway.

Why did it turn out that way?

Christian revivalism research

Bjørg Seland is professor emerita at the University of Agder. Throughout her long research career, the pensioner has focused on Christian revivalism and why it gained such a strong foothold in Southern and Western Norway.

In a study published in 2020, Seland uses an article by the historian and social geographer Gabriel Øidne (1918-1991) as her starting point.

His article Litt om motsetninga mellom Austlandet og Vestlandet - On the distinction between Eastern and Western Norway - was published in the journal Syn og Segn in 1957. It has since inspired Norwegian election research and studies on regional differences in Norwegian politics.

It has also been named one of the most important texts in Norwegian sociology.

Øidne was not a sociologist himself. But he was an early bird in looking for socio-cultural explanations for political and social phenomena in Norway.

Counted houses of worship and Christian magazines

People have always just ‘known’ that houses of prayer were frequent on the coast of Southern Norway and Western Norway.

Gabriel Øidne was not satisfied with this ‘knowing’. He proceeded much more systematically.

“Øidne counted houses of worship, Christian magazines, the number of religious associations and how much money was given to the mission per inhabitant in various places,” says Seland.

“He then looked at voting patterns in general elections over the years. He showed how first the Liberal Party and then gradually the Christian Democratic Party became popular in Southern Norway and Western Norway.

“Support for socialist parties remained correspondingly low.”

Egalitarianism in Southern Norway

Gabriel Øidne was from Lyngdal in Agder county.

The sociologist in him was interested in the egalitarian structures in the south and west of Norway. People’s socioeconomic status there was relatively similar, in contrast to Eastern Norway where society was more clearly stratified, with a greater discrepancy between high and low economic status.

“Along the coast of Southern Norway and Western Norway, the farms had become more and more divided up over generations, and the uncultivated land was often jointly managed,” says Seland.

“People needed to interact and agree on various issues, such as when the cows should be moved between shared pastures.”

This strengthened the sense of community between people on equal footing. According to Øidne, it probably also strengthened a tendency to join groups on an ideological level.

“If you did criticize someone, the criticism was often directed at ‘the authorities’ or at immigrants in the village,” Seland says.

But the division of farms in Southern Norway and Western Norway could only continue so long.

Eventually, several farms became too small for a family to live on. At a time when overseas trade was growing rapidly, more and more people sought a living within the shipping industry for shorter or longer periods of time.

And thus arose the close contact that many southerners and westerners had with Great Britain and eventually the United States.

Evangelization from the United States

“Southern and western Norwegians encountered a completely new type of evangelization in the ports they came to on their trips in the North Sea,” says Seland.

“The period of emigration in the last part of the 19th century strengthened contact across the Atlantic Ocean. Eventually, American New Evangelicalism became an especially strong influence on people from Southern and Western Norway.”

Seland highlights a point she believes many people are not aware of.

“The history in Norway of emigration to the USA has been about all the people who left. But many of those who left also returned," she says.

“We don’t have good figures on how many people came back. But we know that a lot of them returned to Southern Norway in particular. Or we talk about southerners who commuted between the USA and Norway. Many of these individuals brought impulses from American Christian revivalism back with them.”

The influence of trade and shipping

Bjørg Seland also highlights theologian and historian Berge Furre's (1937-2016) contribution to the discussion of religion and modernity.

Furre had a background in the prayer house culture in Rogaland county.

As a student in Oslo he went in a different direction, however. In 1961, he helped found the Socialist People's Party. He became party leader when the party later changed its name to SV, the Socialist Left Party.

“Furre spoke out against the common perception of the house of prayer culture as something backward and unfashionable,” says Seland.

As a historian, Furre saw how southwestern Norway in particular had early on begun to modernize.

This part of Norway had not been very industrialized, but trade and shipping had established close links between Southern and Western Norway and the international monetary economy.

An international trend

Øidne was primarily concerned with documenting regional differences in voting patterns.

More recent researchers, such as Furre and Seland, have focused more on explaining how and why such differences arose.

It was not a given that the tendency towards interaction and consensus that Øidne highlights would lead people specifically to houses of prayer.

Seland emphasizes that Christian revivalism is far from a peculiarly Norwegian phenomenon.

What we see in Southern Norway and Western Norway is closely linked to an international cultural trend in the Western world, she says.

“In my study, I highlight how strong the influence of shipping was.”

“Emigration to the USA and people who returned from there are also a major factor in understanding the background of the Norwegian Bible Belt.”

‘You can be saved today!’

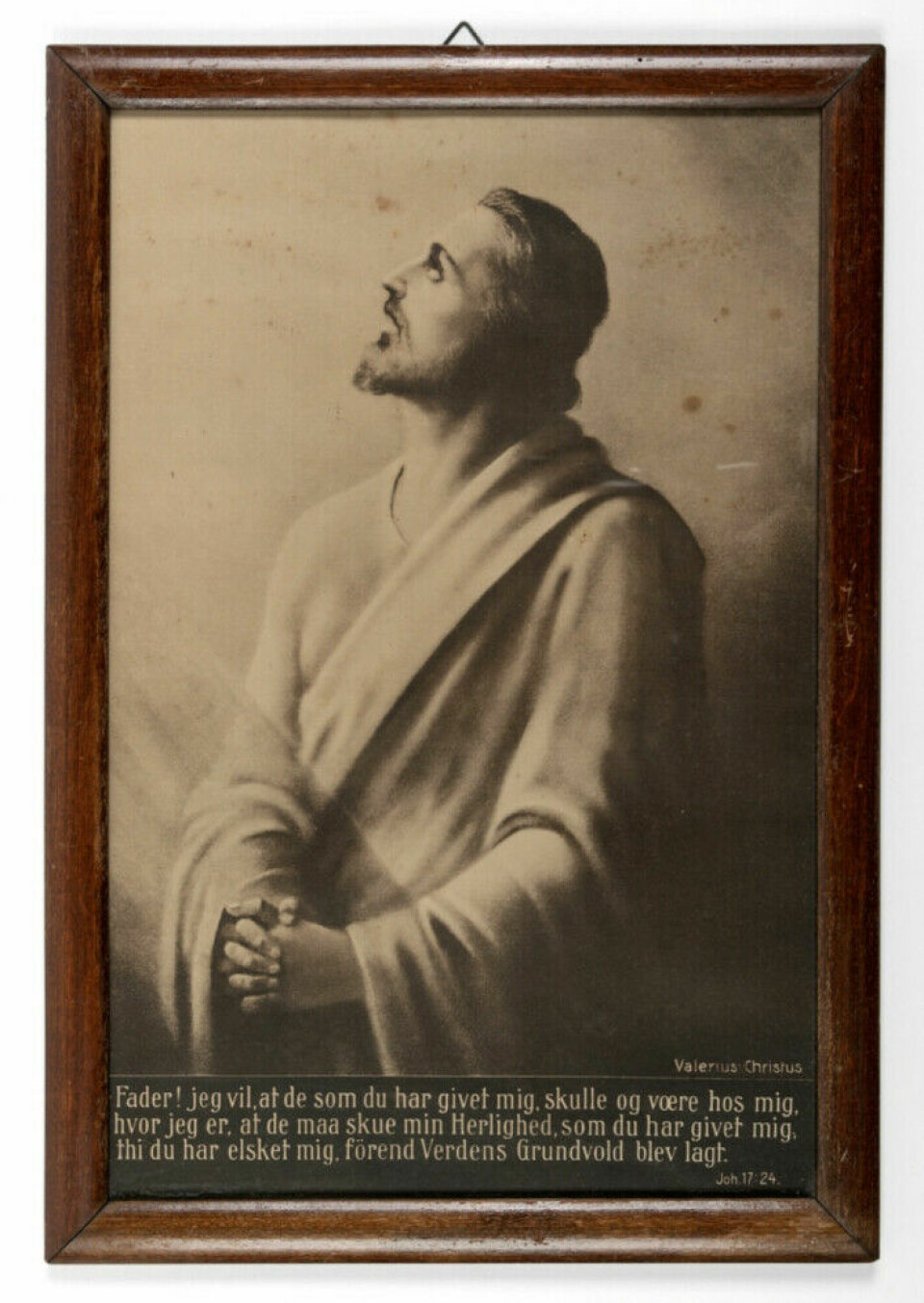

In traditional Norwegian Lutheranism, priests had preached that you could only move gradually and painstakingly in the direction of salvation.

The new evangelical preachers who drew inspiration from the United States placed greater emphasis on the message of grace.

Their Christian agitation was both bold and persistent.

A typical slogan was: ‘Come as you are – you can be saved today!’

New Christian songs with rhythmic melodies also had strong appeal and helped to attract young people to religious meetings.

Together, these factors can probably explain why Southern Norway and Western Norway became Norway’s Bible Belt.

References:

Bjørg Seland: Det norske bibelbeltet. Geografiske og kulturhistoriske perspektiv (The Norwegian Bible Belt. Geographical and cultural-historical perspectives. Historisk tidsskrift, 2020. (in Norwegian)

Gabriel Øidne: Litt om motsetninga mellom Austlandet og Vestlandet (On the Distinction Between Eastern and Western Norway). Syn og Segn, 1957.

———