People kept quiet about the war: Talking too much about traumatic events also has a downside

Sailors, torture victims, and war veterans often did not talk about their experiences from World War II. Researchers explain that they had their reasons.

Fathers never talked about what they had experienced, descendants of war prisoners from World War II recently recounted at a seminar (link in Norwegian).

Professor Trond Heir has met many people in his job as a psychiatrist who experienced the Second World War. He confirms that it is not uncommon for sailors, torture victims, and war veterans to refrain from telling their families about what they had experienced.

“People who’ve experienced traumatic events often have a need to avoid anything that reminds them of those events. Talking to their loved ones made it more difficult to distance themselves from the memories,” says Heir.

Three historians and a psychiatrist agree that the reasons for the wartime generation's silence are numerous and complex.

They were expected to be strong

Prisoners and wartime sailors were mostly men.

“According to the gender roles of the time, men were expected to be the pillars of strength within their families. They didn’t want to expose their loved ones to emotional discomfort over what they’d experienced,” says Heir.

Heir is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oslo and studies trauma and disasters at the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies (NKVTS).

“They didn’t want to portray themselves as victims, preferring instead to embody the prevailing ideals of masculinity. This made it difficult for them to talk about their deepest emotions,” says Heir.

Bjørn Tore Rosendahl is a historian at the ARKIVET Peace and Human Rights Centre. He has spoken with descendants of wartime sailors and prisoners.

“They mostly talk about how their father, and sometimes mother, didn't tell them anything," he says.

Better to know

Testimonials given by sailors after torpedo attacks and shipwrecks have now been published in a War Sailor Register on ARKIVET’s Centre for the History of Seafarers at War website.

“A child of a sailor who had never spoken about his wartime experiences found his father's testimony. Here was the father's account of what he had endured,” says Rosendahl.

Children saw that their parents were struggling, but did not know why.

“For a lot of the children, it would've been better to know why their father had problems than to learn about them afterwards. Parents' hidden truths can make their children's lives more difficult,” says Heir.

Wouldn’t understand

“Several wartime sailors have said that they believed those at home wouldn't understand what it was really like in captivity and on the ships,” says Bjørn Tore Rosendahl.

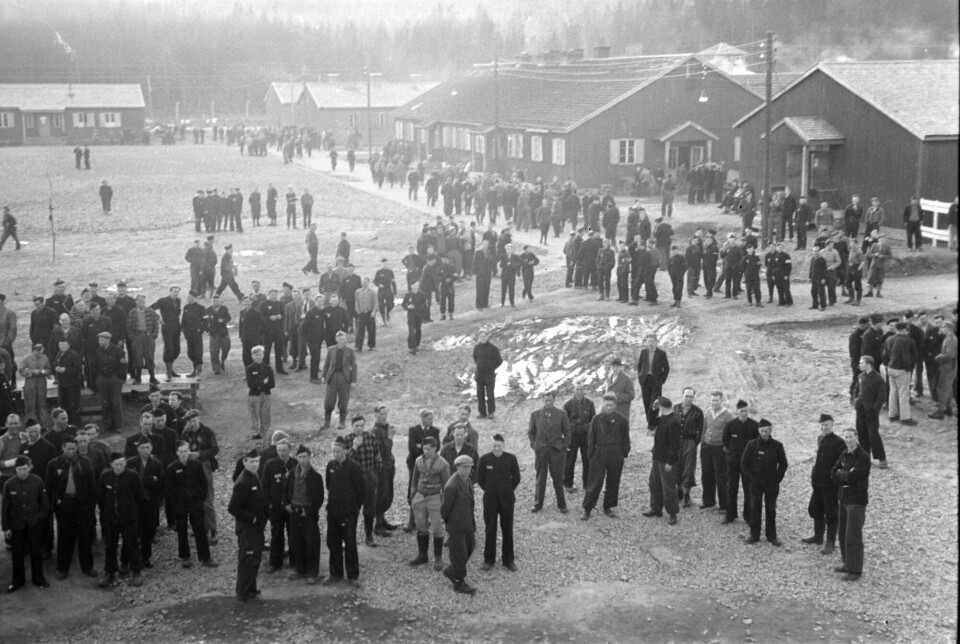

Many veterans experienced extreme things. Wartime sailors lived in fear of torpedo attacks. They saw comrades drown or ended up in the perilous sea themselves. Prisoners were tortured, worked to the bone, and starved.

“Those who returned home lacked a common language and shared references about their experiences during the war. I think a lot of them wanted to spare their loved ones from what they’d endured. They may also have felt shame if they had suffered degrading experiences,” says Rosendahl.

Historian Guri Hjeltnes has worked extensively on Holocaust history.

“The Jewish experience was incredibly dramatic. So many family members were lost. A lot of people said that they just wanted to move on. They didn't talk to their children about the war because they wanted them to have a normal childhood – without a heavy burden,” says Hjeltnes.

Afraid of not being believed

Perhaps the fear of not being understood or believed was so great that it was easier to remain silent.

Samuel Steinmann was one of the few Norwegian Jews who survived Auschwitz.

“Steinmann mentioned that he was interviewed by Swedish newspapers in Stockholm when he returned home in the summer of 1945. The journalists doubted his story. That's when he stopped talking about his camp experiences, and it took many years before he told his story,” says Hjeltnes.

It was not until 2012 that the Norwegian police apologised for their involvement in the deportation of Norwegian Jews. The official apology to the war sailors for how Norway had treated them after 1945 came in 2013.

Interesting enough?

“My experience with both seamen and other veterans is that a lot of them haven’t considered their personal experiences to be an interesting or valuable story for the general public,” says Hjeltnes.

A wartime sailor told Hjeltnes that those at home knew nothing about what the men at sea had been through. Those who sailed abroad deeply respected those at home who had been occupied for five years.

Some of the veterans also felt that they had not experienced enough.

“Sailors who made it through the war without being torpedoed might have a guilty conscience. They had seen friends drown, while they themselves survived with their health intact,” says Hjeltnes.

The wartime sailors were constantly informed about the war in Norway.

“To keep the sailors motivated, they were given a lot of information about how terrible things were at home in Norway," says Bjørn Tore Rosendahl.

“They admired the resistance efforts at home and perhaps underestimated their own contributions."

Was effort enough just to go on

Prisoners and wartime sailors had to make up for lost time. The majority of the sailors were under 30 years old.

“Their friends at home had started families and completed their education. They had years to catch up on, so they needed put the war behind them,” says Guri Hjeltnes.

Not only did Norwegians have to move on and rebuild the country, but they also went straight into the Cold War.

“A new threat surfaced very quickly. This also contributed to making the war less important to people,” says Rosendahl.

Lack of interest in the war

Moreover, interest in the war rapidly declined.

“When I do media searches, I get many hits for 1945 and 1946. But after that, interest seems to drop quickly. I find far fewer hits from 1947, and even fewer from 1950. It looks like people were mostly focused on moving on,” says Rosendahl.

When Norway was liberated on May 8, 1945, there was great joy, optimism, and celebration. The wartime sailors were still out at sea, and it took time for them to return home, a few at a time. Many did not return home until 1947.

“By then, everyone else had finished celebrating and moved on from the war. When the sailors finally came home, they found that people weren’t interested in their experiences and that they knew very little about the risks and efforts of the Norwegian merchant fleet,” says Rosendahl.

The silent generation

The gap between the generations was also greater at that time.

“I was born in the 1950s, and we never talked to our parents about what was important in our lives. And gwe weren't very interested in our parents' lives while growing up either. It’s completely different now,” says Hjeltnes.

Openness about painful experiences was not common.

“At that time, there was no culture or expectation that you should talk about difficult experiences. Instead, you were expected to keep it to yourself,” says Rosendahl.

Suppressing or forgetting events was considered the best way to deal with painful things. They would eventually pass.

It could get worse over time

Even though war veterans didn't talk about their experiences, they had 'nerve problems', which was the term used for mental health problems at the time.

“When the prisoners came home, they reported their experiences in police questioning, as part of the legal proceedings after the war. Many stated that they had nerve problems, but that it would probably pass. They might have believed that silence was a good strategy for recovery,” says Rosendahl.

KZ syndrome is the term given to describe the traumas from concentration camps. It develops gradually over the years and is a late consequence of prolonged physical and psychological abuse, infections, and malnutrition, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia (link in Norwegian).

Symptoms include memory loss, mood swings, depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and a constant feeling of being threatened. It resembles post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Wartime sailor syndrome is similar.

Openness is not always beneficial

Many war veterans drank too much.

“Talking about their problems would clearly be better than trying to drink them away,” says psychiatrist Trond Heir.

“But openness isn’t always a good thing. It has to be nuanced,” he says.

Today's culture of openness around mental health problems does not necessarily improve a person’s mental health, according to Heir.

“Today we believe that talking about painful feelings and experiences is almost exclusively good. But this is not an absolute truth. If openness were the best strategy, you’d expect it to be reflected in mental health statistics, but it isn't,” Heir says.

On the contrary, our preoccupation with mental health problems may contribute to mental ill-health, he believes.

“Talking too much about trauma and painful events also has a downside. It can become part of your identity. Events that we perceive as central to our lives can easily dictate how we feel about ourselves and others. Ultimately, this is what defines mental health,” says Heir.

What would happen today?

There were not many psychiatrists and psychologists in Norway after the war. But what support would prisoners and wartime sailors receive today?

“The most important thing is to receive recognition and support to live as normal a life as possible. We encourage using family and networks for support, but without exhausting them,” says Heir.

Understanding the connection between what you have experienced and your own reactions is also crucial.

"This understanding can make it possible to put painful events behind you and be present in the life to be lived," says Heir.

Establishing routines for school or work, meals, sleep, and physical activity is also key.

“Some people benefit greatly from professional help. We have ways to treat trauma today that can provide relief and help someone move forward after experiencing traumatic events,” he says.

Talked to historians

But even if the veterans didn't talk to their families, they did talk to the historians.

“I’ve interviewed many war veterans, both as a journalist and historian, including more than 100 wartime sailors. I was often warned by their wives that I probably wouldn't get anything out of them, but I actually rarely encountered resistance. Usually they found it exciting to be interviewed by a researcher,” says Hjeltnes.

Trond Heir thinks it was easier for veterans to talk to historians after some years had passed. By then, veterans had more control and distance from the events.

Bjørn Tore Rosendahl also spoke with wartime sailors and prisoners.

“They talked to me, but I regret not asking more about why they didn't talk to their loved ones about what they experienced,” he says.

The right questions

Greater societal openness has helped researchers.

“That’s why it might have been easier for us historians who came a long time after the war to get the veterans to share their stories,” says Rosendahl.

Historian Gunnar Hatlehol from The Narvik War and Peace Centre also researches World War II.

“My own experiences with witnesses from the war taught me that it’s important to ask the right questions if you want to get the person to talk. You have to ask questions based on some familiarity with the kinds of experiences the person had during the war years. That usually triggers a response,” says Hatlehol.

Although many war veterans remained silent for a long time, their stories have nevertheless come to light.

“Many war witnesses eventually spoke up,” says Hatlehol.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no