What is a hypersonic weapon?

They move very, very fast, but that's not the most important thing about these weapons.

In recent years, the United States, China, Russia and North Korea, among others, have been testing and developing what are called hypersonic weapons.

On March 18, it was reported that Russia had used hypersonic missiles in the ongoing war in Ukraine, according to the BBC. The missile, called the Kinzhal, is fired from an aircraft and can have a range of up to 2,000 kilometres, the British broadcaster reported.

In the past, two Chinese tests in 2021 in particular have attracted attention, according to sources in American intelligence that were interviewed by the Financial Times newspaper.

US military authorities have identified hypersonic weapons as a focus area, and they are said to have been surprised at how far China had come in developing the weapon, the newspaper reported.

Russia is said to have tested several different types of hypersonic weapons in recent years. One of these tests took place on 23 February this year in the waters between Norway and Svalbard, according to the Barents Observer.

Big difference in the weapons

But there are big differences between all these different weapon systems. Some are long range, and some have a shorter range. All are referred to as hypersonic weapons.

Some can be used to deliver nuclear weapons, while others deliver conventional explosives. So what are we actually talking about, when we talk about hypersonic weapons?

sciencenorway.no has talked to Halvor Kippe at the Norwegian Defense Research Establishment about this type of weapon.

“The common denominator is that these are weapons that are difficult to defend against,” Kippe said.

In theory, hypersonic weapons can bypass defences, manoeuvre in the air and make themselves difficult to detect using radar and warning systems. But how do they do that?

Fast, faster — and manoeuvrable

“These weapons go faster than five times the speed of sound,” Kippe said to sciencenorway.no. He specializes in nuclear weapons and countries with a nuclear arsenal.

The speed of sound is often called Mach 1. This corresponds to around 1,200 kilometres per hour.

The word hypersonic means that the weapon can go faster than Mach 5, but this is nothing new in itself. Mach 5 is roughly 6,000 kilometres per hour.

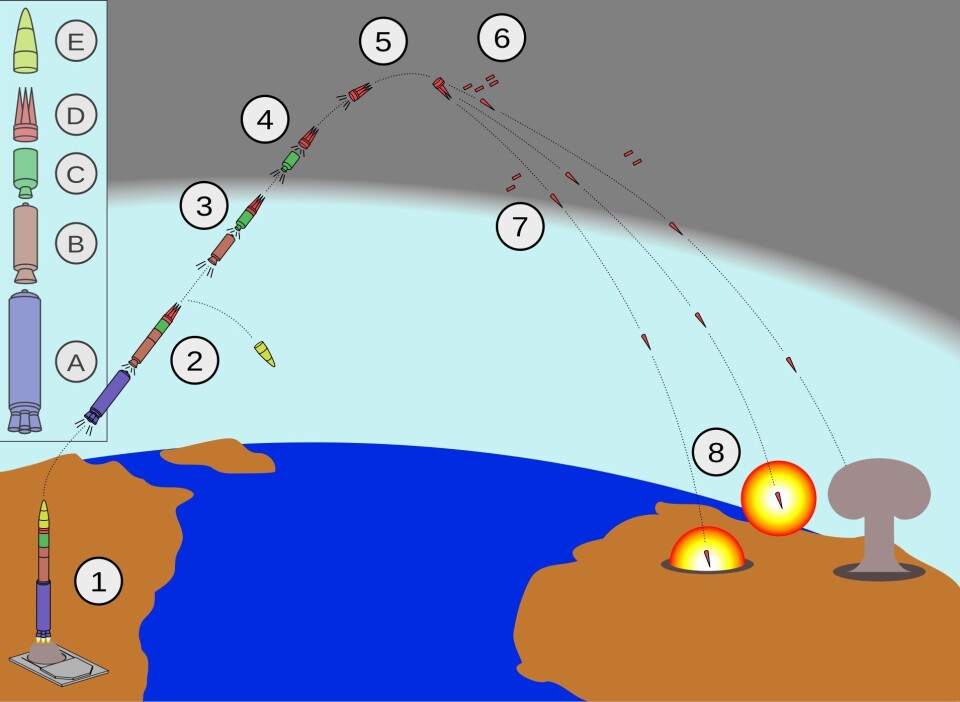

Traditional ballistic missiles can go much faster than this, and have been in use for more than 60 years. They can be launched from submarines, and are shot far beyond the atmosphere, into space, before falling to the ground again, in what is called a ballistic trajectory.

These are called intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and have a range of more than 5,500 kilometres, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

When the actual warhead is on its way back down through the atmosphere, it can reach enormous speeds, well over 20,000 kilometres per hour, or up to Mach 20. But it follows a predictable orbit.

Over the course of several decades, Israel, the United States, Russia and the United Kingdom, among others, have developed missile defences. These systems consist of rockets that can be launched to stop ballistic missiles in the air.

But it’s possible to try to predict where ballistic missiles will fall and thus intercept the missiles when they re-enter the atmosphere — essentially by striking the missile with another missile.

The idea behind hypersonic weapons is that they go very fast — while at the same time they can be controlled like a kind of aircraft in the atmosphere. They may have the same range as more traditional ICBM rockets, but they always stay in the atmosphere.

This makes them quite unpredictable and difficult to monitor. In theory, hypersonic weapons can manoeuvre away from defensive missiles.

Kippe says this ability to be controlled in the air combined with their high speeds are the weapon’s central features.

Different varieties of weapons

Hypersonic weapons can be put into three different categories, according to National Public Radio, NPR, an American public broadcaster. These are either ballistic missiles that can be guided when they return to the atmosphere, flying cruise missiles that have their own engine, or hypersonic gliders. These are always unmanned.

The differences come from their range, properties and how they reach their highest speeds.

Most people talk about hypersonic gliders when they refer to hypersonic weapons, Kippe said. These can also be used to send nuclear weapons to targets around the world.

This is something different than the hypersonic missile that Russia is said to have used in Ukraine.

Glides through the air at thousands of kilometres per hour

Hypersonic gliders are airplane-like missiles that are first accelerated at rocket speeds, before being able to glide for many thousands of kilometres per hour through the atmosphere in a flat orbit. From this location they can be guided towards a goal.

“They are also more difficult to follow using radar,” Kippe said.

In theory, these weapons can travel fast, fly low, manoeuvre away from possible defensive weapons and hit a target using nuclear weapons.

China is said to have carried out several tests of possible hypersonic weapons, although they deny that they are weapons, according to the BBC. One of these tests is said to have sent a rocket-propelled glider around the globe, before aiming at a target on the ground.

The weapon is said to have missed its target by many kilometres, but US intelligence believes the test shows that China has far more advanced weapons than previously thought, according to the Financial Times.

Kippe also described another test reported by the Financial Times. China is said to have tested a variant called a FOBS (Fractional Orbital Bombardment System), according to the newspaper. This is an idea for a weapon that was first developed in the Soviet Union, and that consists of several parts. But China may have developed it further.

A rocket is launched into orbit around the world and carries hypersonic missiles. The weapon can then be braked while in space to hit a target along its trajectory, giving the weapon almost unlimited range, according to Space.com. This makes the weapon more unpredictable, and can make for a very short warning period.

“You aim a missile defense in a direction where you think something is coming in, but in this situation it can come in from all directions,” Kippe said.

Kippe describes a weapon system like this as "very destabilizing".

But China itself has not confirmed that it has these weapon systems, according to The Guardian.

The United States is working to develop its own hypersonic weapons, and plans to have a functioning, hypersonic weapon variant ready for use in 2022, according to Bloomberg.

Technical challenges

When something moves at many thousands of kilometres per hour through the air, it can put extreme stresses on planes or weapons.

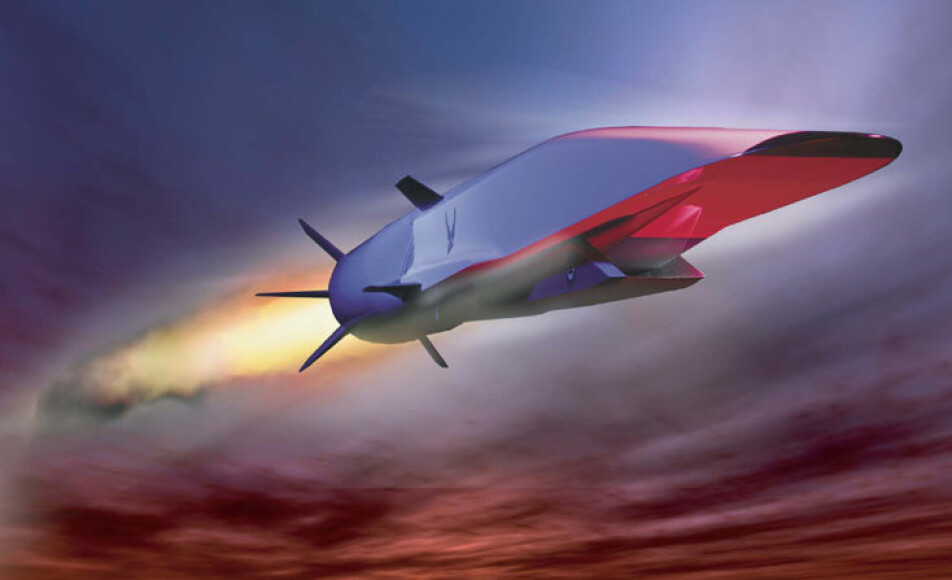

The US military research organization DARPA tested the concept of the hypersonic glider HTV-2 in the early 2010s (pictured at the top of this article). It glided through the air at 20,000 kilometres per hour in the atmosphere, and had to withstand temperatures up to 2000 degrees due to the extreme friction against the air.

The air resistance also means that the gliders have to use a lot of force to turn and manoeuvre when they go so fast — which nevertheless is also their great advantage. They can lose a lot of speed in manoeuvring due to the friction in the air.

“The point is that when you fly hypersonically in the atmosphere and start manoeuvring, you are no longer hypersonic. Then it may not be completely impossible to defend against it or stop it,” Kippe said to sciencenorway.no.

Hypersonic gliders may not be as effective as those described by the great powers, according to scientists David Wright and Cameron Tracy in Scientific American.

The two authors describe several possible problem areas for hypersonic gliders, such as that missile warning systems may be able to detect them. As these missiles fly through the atmosphere, they become so hot that existing missile warning satellites can detect them, Wright and Tracy wrote.

A frightening picture of hypersonic weapons?

The American journalist and author Fred Kaplan specializes in war and war history. He has tried to de-dramatize hypersonic weapons in this column in Slate Magazine, and wonders if the Pentagon has an interest in creating a frightening picture of hypersonic weapons as a means to justify large defense budgets.

Kaplan wrote that an advanced hypersonic weapon could in theory bypass the US missile defense systems, but that the Chinese weapons are not yet good enough to pose a threat.

At the same time, missile defense has never been shown to work against two simultaneous ballistic missiles headed to the same target, which is a potentially much easier way around any missile defense system, Kaplan wrote.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no