Why are 377 whale foetuses preserved in alcohol at Norwegian museums?

There is not room for everything in museum exhibitions. But what is stored away also tells a story.

Palaeontologist Lene Liebe Delsett has investigated the types of whale remains stored at the natural history museums in Norway’s capital Oslo, Bergen, and Denmark’s capital Copenhagen.

As many as 2,500 whale specimens have been catalogued in her study. Where possible, she has gathered information on when and how each of them reached the museums.

There are many foetuses in the collections.

In Bergen, there are 31 whale foetuses in alcohol and in Oslo, there are 66.

At the Natural History Museum in Oslo, they are stored in a small outdoor warehouse.

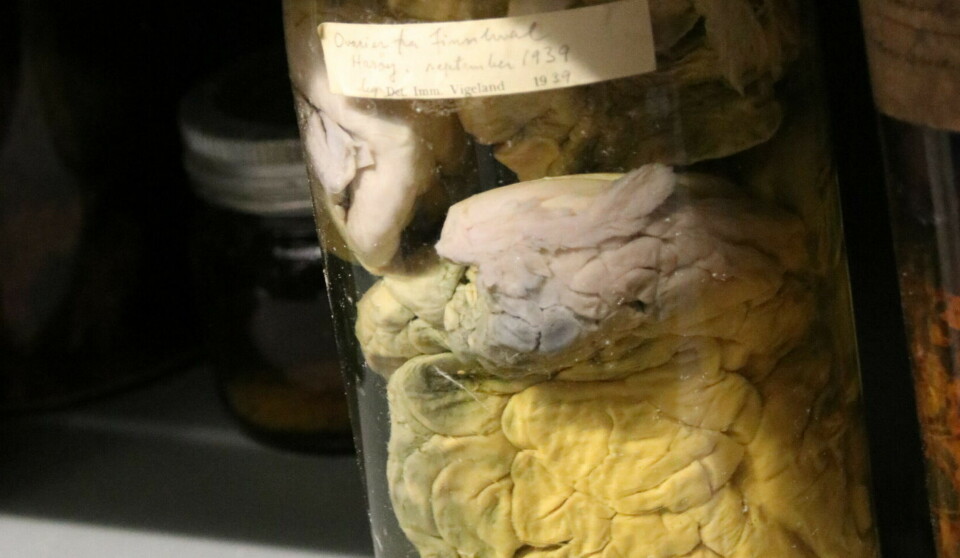

There is a yellow tint in the hundred-year-old jars. Inside are small whales that look like mini versions of the adults.

“This is a porpoise. It's quite cute,” says Delsett.

In some jars, there are greenish-yellow internal organs.

An internal organ from a blue whale from South Georgia is one of the traces of the industrial whaling in the Southern Ocean.

In another jar, there are ovaries from a fin whale. Blubber was also something that was collected.

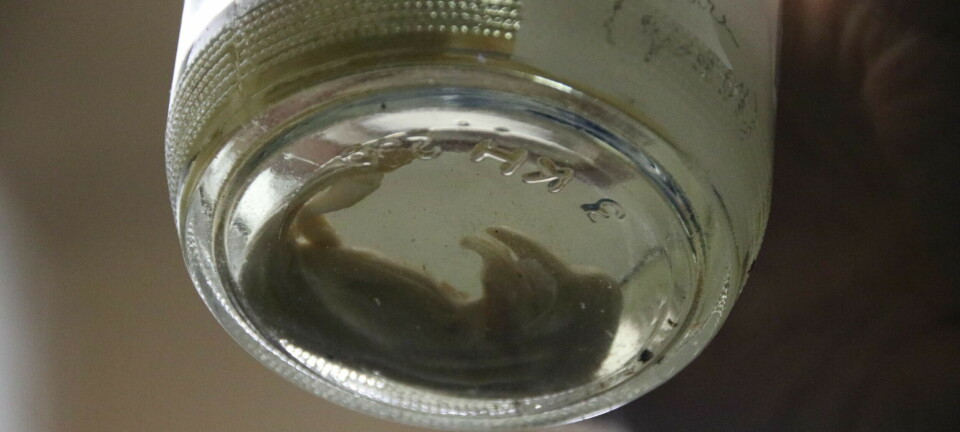

In a box, there are small jars with the smallest foetuses. Delsett finds them special.

They were cut out of the mother's womb when they were at an early stage of foetal development.

“There’s something melancholic about baby whales preserved in alcohol,” Delsett says.

Studied foetuses

Why so many foetuses?

Delsett explains that in Bergen, there was research conducted on foetal development in whales.

Whale foetuses were also easy to store whole. The Danish researcher Daniel Frederik Eschricht, who lived in the 19th century, argued that whale foetuses were important objects of study. They had little economic value, and collecting foetuses made it possible to study the entire anatomy of whales in miniature form, Delsett writes this in the study.

In Oslo too, there are quite a few whale foetuses, but much less published research about them.

The narwhal

Delsett has researched whale collections through the Collecting Norden project at the University of Oslo’s Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History. She is also a researcher at the Natural History Museum in Oslo.

From the museum’s storage, she shows a skull from a narwhal that had two ‘horns’. They are quite rare.

These are not actually horns, but long, spiral-twisted tusks. One of the tusks in the narwhal's upper jaw grows as the whale ages and eventually protrudes like a spear.

Narwhals were popular because of this long tusk.

“People have been fascinated by them for a long time. There has been a lot of buying and selling of tusks. They are the origin of the unicorn myth, and there has been a strong belief that the tusks possess magical powers,” she says.

But there are more treasures in storage.

An old cigar box contains some small, fragile bones.

Another box contains lumpy bones. There are bones that were in a whale’s ears. They are about the size of a fist.

They come from a blue whale foetus, Delsett says.

Norway was a leader in the hunting of large whales from the end of the 19th century and for many decades thereafter.

This is hardly reflected in the collections stored at the Natural History Museum in Oslo and the University Museum in Bergen, according to Delsett.

“I was surprised. Since Norway was a superpower in whaling, especially in the Southern Ocean, one would think that this would be evident in some way. But it really isn’t,” she says.

Instead, there were many small whales in stock, such as dolphins, porpoises, and narwhals.

Random hunting

In Norway, the hunting of toothed whales along the Norwegian coast has been happening for several hundred, perhaps even thousands of years, says Delsett.

Toothed whales are whales with teeth, such as dolphins, porpoises, and orcas.

The hunting of large whales, like blue whales and humpback whales, was conducted on a large scale. Large ships and technology were developed to catch them and process the carcasses. Norway was especially active in the Southern Ocean near Antarctica.

The hunt for the smaller toothed whales was much more random. Opportunities were taken as they presented themselves, Delsett notes.

“It was more like: Oh, here comes a pod of dolphins, let’s catch them,” she says.

People used whatever equipment they had at hand.

“Perhaps a mackerel net was used, or they were clubbed on the head, or herded into shallow waters,” she says.

Dolphin from Drøbak

Delsett highlights a favourite among the whale skeletons stored at the Natural History Museum in Oslo.

A spine with ribs closely packed together and a head in a box are the remains of an Atlantic white-sided dolphin.

The dolphin was caught in Drøbak in the Oslo Fjord in 1842. This is one of the oldest whales in the collection that is not from prehistoric times.

“A pod of about 22 animals came. A farmer saw them out of the window and probably thought, ‘we must catch them’,” Delsett says.

The fishermen managed to get the dolphins onto land and thought they were special. The Natural History Museum agreed and wanted the species in their collection.

Another example is from Bergen in 1885. A thousand white-sided dolphins gathered in a fjord. 200-300 were killed.

Fridtjof Nansen, who was working at the Natural History Museum in Bergen at the time, arranged for the purchase of foetuses and skeletons.

Most viewed

No content

Whaling in Norway

The hunting of small toothed whales is prominently featured in museum collections. The harbour porpoise, a common species in Norwegian waters, is frequently found in these collections, as noted in the recent study.

Among the baleen whales, there were many specimens of minke whales. Common both within and outside Norwegian territories, minke whales are among the few still legally hunted today, with other forms of whaling being illegal.

Specimens from the era of large-scale whaling off the coast of Northern Norway also exist. This region was the cradle of Norway's industrial whaling, which continued until it was banned in 1904.

The natural history collection in Bergen features about 20 complete whale skeletons in its whale hall, including a 24-metre-long blue whale caught in Finnmark in 1878.

Some of the whales in the various collections have been collected after they have been stranded. Some come from expeditions to remote areas.

Collections like these should not be made again

Delsett was particularly moved by the blue whales in the collections.

“Their sheer size is overwhelming; they are the largest animals to have ever lived. Whenever I encounter the blue whale specimens, I'm filled with reverence. The unique aspect of the blue whale specimens is the consensus that they cannot, and should not, be collected again,” she says.

Anatomy fell out of favour

Few of the whale specimens she found originate from the large-scale whaling in Antarctica, where a vast number of whales were killed. Norway led the way for a long time.

Eventually, several nations participated. The hunt drove many species to the brink of extinction throughout the 20th century.

Oslo has no more than 21 specimens from the Southern Ocean, and Bergen has 8.

Delsett believes it’s a matter of timing.

“Most of the whales in museum collections were gathered at the end of the 19th century,” she says.

That was when the institutions were being established. Norway was separating from Sweden. Having national museums was important, according to Delsett.

“Anatomy was popular. There was an effort to understand how animals looked and developed. Whales were exchanged with other animals from museums abroad,” she says.

However, by the mid-20th century, when whaling in the Southern Ocean was at its peak, objects and anatomy no longer received as much attention in biological research.

New possibilities

Now that Delsett knows what exists in the museums, what can this information be used for?

New technology and research methods allow for new information to be extracted from the old materials.

It is important to uncover the biases that exist within the material, she believes.

“Collections are not a one-to-one representation of nature,” says Delsett.

The species collected and their origins do not necessarily reflect their distribution in nature. Culture and society play a role.

For example, the Danish collection has many narwhals and other species from around Greenland due to their colonial history.

It’s possible that more males of a species were collected because the males look more impressive. Or that invasive species have not been collected.

Did not know what questions would be asked in the future

It is now possible to examine the DNA from the specimens. Or to look at what kinds of environmental toxins are in the old whales.

“There’s also still a lot we don’t know about skeletons, soft tissues, and foetal development,” she says.

However, the future utility of these findings is yet to be determined, Delsett points out.

“People who collected whales in 1880 couldn’t have known that we would have fantastic genome data methods or what questions we would want to ask now,” she says.

Reference:

Delsett, L.L. Collecting whales: processes and biases in Nordic museum collections, PeerJ, vol. 12, 2024.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no