Will Iranian women succeed in overthrowing the regime?

Half a year after the protests in Iran started, people harbour both faith and doubt as to whether the revolution will succeed.

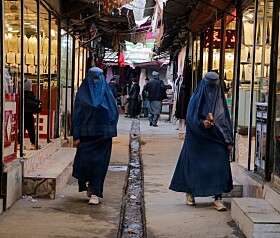

The protests started last autumn in the streets of Iran. They began when 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died after being arrested by the morality police for not following state hijab rules.

The demonstrations initially received abundant media coverage worldwide. Now the reporting has become quieter.

“I’m not seeing much in the international media now about what’s happening in Iran. But there’s a big feminist revolution that both men and women are participating in,” Shirin Ebadi said in a recent video interview at a meeting of PEN Norway in Oslo.

Ebadi is an Iranian lawyer, former judge, political activist and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.

“People want to bring down the government, and it is faltering now,” said Ebadi.

She is optimistic on behalf of the Iranian people.

Opposition currents need to cooperate

Iran previously had two political currents, according to Ebadi. The disagreement has been between people who want to continue as a republic and those who want the monarchy back.

Monarch Shah Muhammed Reza Pahlavi was overthrown in 1979, and the Islamic Republic was subsequently established. Both inside and outside the country, many Iranians want the old system of government back.

“This disagreement has contributed to the longevity of the government’s hold on power in Iran. Now the opposition needs to work together,” Ebadi said in her interview.

The regime is cracking down hard on protesters.

Nearly 20 000 demonstrators have been arrested. Several have received long sentences or the death penalty. Close to 500 protesters have been killed by the security forces, according to the Iran Human Rights organization.

PEN Norway, Amnesty, the UN and several other organizations work to assist political prisoners in Iran.

Demonstrations of support have also been held around the world.

Not as intense now

Kjetil Selvik is a researcher at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. He specializes in working with state and regime conflict in the Middle East, including Iran.

He is following the protests in Iran closely.

“The protests are not as intense now as last autumn, when there were daily demonstrations in the streets. We’re no longer seeing that now,” Selvik says. “We no longer get daily and weekly reports about protests, but the people in Iran are continuing to express their dissatisfaction.”

He believes the celebration of Nowruz, the Iranian New Year, is one of the reasons protests have slowed down a bit.

“But the demonstrators are still continuing. We see the protests flare up all the time. Resistance is expressed in many ways – what we call everyday resistance. There are small acts of protest in daily life that are not that easy to see or understand from a distance.”

Regime not prepared

Selvik is sure that the anger and discontent that caused the protests last autumn has by no means disappeared.

The demonstrations have lasted longer in certain parts of the country. Selvik mentions Zahedan in Baluchistan, where the authorities fired at protesters intensely last September.

“One Friday prayer leader with a lot of followers is very critical of the regime. The fact that the regime has killed so many has made the rebellion tenacious,” says Selvik.

The rebellion arose spontaneously last autumn. It had no leaders and no organisation was behind it. The regime was not prepared.

“It was difficult for the regime to suppress the protests. They didn't know whom to go after. Now they’ve had time to think about it,” says Selvik. “The regime has had more time to identify what they perceive to be their most dangerous opponents. They’re monitored, imprisoned and tortured.”

Calmed down other conflicts

The Iranian regime is under pressure from several quarters, according to the researcher. The protests in the country have led to increased pressure from Western countries.

The regime has taken countermeasures.

“To avoid too many conflicts at the same time, Iran has buried the hatchet with Saudi Arabia. They have also tightened their alliances with China and Russia,” says Selvik.

He sees no signs that the regime is faltering.

“Although all the protests are a challenge, they haven’t led to open divisions in the security apparatus, refusal of orders or other cracks in power that are necessary for a regime to fall.”

Iran has an extensive security apparatus that controls the population through surveillance and reprisals. In addition, the regime is based on ideology and indoctrination.

The regime also has support in parts of the population.

Revolution or not?

“There are three main groups – people who protest, those who actively work for the regime and others in the middle who do neither. The last group is the largest,” says Selvik.

He believes many people have become critical of the authorities because of the way they have cracked down on the protesters.

The activists call what is happening now in Iran a revolution. But not all researchers agree, according to Selvik.

“Some historians and political scientists are more restrictive in using the term revolution. They only use it when movements have succeeded in overthrowing a regime. The revolution in Iran in 1979, when the Shah was overthrown, is an example of such a revolution.”

Other researchers are more in line with the activists and say that a protest movement with the goal of fundamental political change can also be called a revolution.

Headed in the right direction

“In any case, what’s happening in Iran now is a revolutionary movement. The protesters don’t want to reform the regime from within, as other Iranian movements have tried to do in the past.”

Selvik thinks it is difficult to say whether the protesters will succeed.

“Today there’s no indication that the regime is about to fall. It may seem that the repression has had an effect. But what happens in the medium term is still an open question.”

Ebadi, on the other hand, has no doubts:

“The revolution is headed in the right direction. We’ll win, that's for sure.”

Translated by: Ingrid P. Nuse

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no