St. Lucia's Day:

An Italian saint, a German child and a female demon all play a role in the story of 13 December

The St. Lucia celebration in Sweden can be traced to the end of the 1700s or early 1800s, while it is still fairly new in Norway.

Saint Lucia (often St. Lucy in translation) became a martyr in the year 304 when she chose to dedicate her life to God, instead of marrying. Her name comes from the word "light", and her name day in the West is December 13.

But the Scandinavian tradition on St. Lucia Day isn’t solely based on the Catholic saint. Another inspiration may have been a German alternative to the Catholic St. Nicholas — the forerunner of Santa Claus.

And before the Lucia celebration came to Norway, the night of 13 December was already an important date. That was when the terrible female demon spirit Lussi wandered the night to check if people were finished with their Christmas preparations.

A kind of beauty pageant

But let's start with the modern Lucia celebration. This is the one where children and adults walk in a parade wearing white clothing and hold lit candles in their hands or in a wreath on their heads — and sing the Lucia song.

This is a relatively new custom in Norway, imported from Sweden, says Herleik Baklid, an associate professor at the University of Southeast Norway.

He thinks the Lucia tradition began to spread to Norway after 1927. This was the first time a Swedish newspaper featured a big story about the tradition.

“That created the modern Lucia and shifted the celebration from the private sphere into the public space,” says Baklid, who has studied Norwegian holiday traditions.

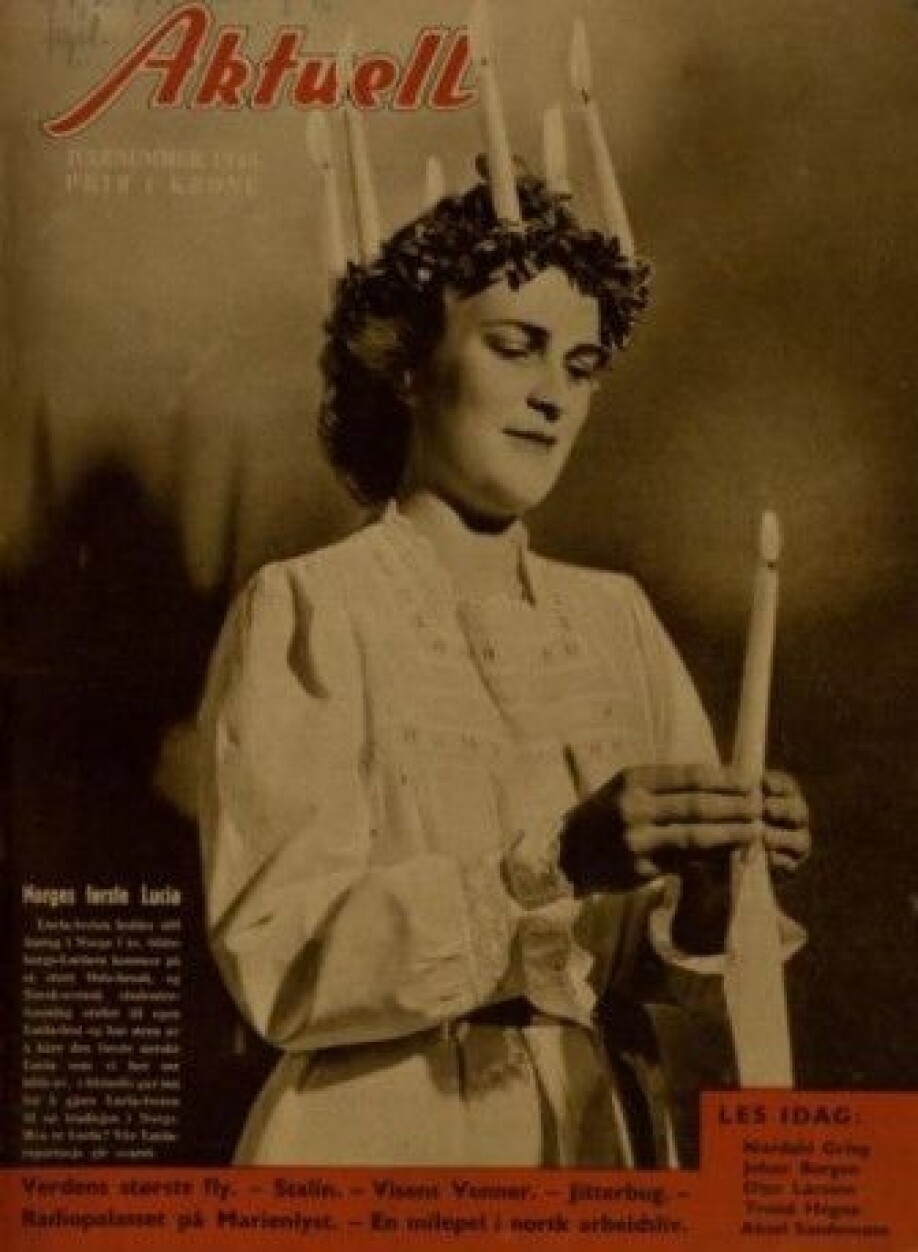

In 1945, Norwegian students also crowned their first Lucia, according to the weekly magazine Aktuell. The front page of this issue also explains that Gothenburg's Lucia was visiting Oslo that day.

“Previously, there was a competition to be the finest Lucia, a kind of beauty pageant. That’s an element that has fallen away,” Baklid says.

Served food to the family

But long before any public beauty pageants, the tradition started at people's homes.

There is evidence of the celebration in Sweden all the way back to the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century.

The celebration involved a woman wearing a white dress, preferably with a wreath on her head with candles, and she would serve food and drink to others in the family.

Gradually, more and more people began to follow the Lucia tradition, including women who looked a bit like Lucia and who were called “terner”.

Lucia and her helpers also became popular in social groups. And then students took ownership of the tradition.

“Eventually, this was picked up by student communities such as in Uppsala and Lund. What was a little funny then was that Lucia was typically a man and not a woman,” says Baklid.

A German Christmas tradition with a white-clad girl

But why did the Swedes really start celebrating an Italian saint?

“It's an interesting question. These customs can be transferred with the help of people who move and then they can be transformed and adapted to their home countries,” Baklid says.

At the same time, one theory holds that part of the custom doesn’t actually originate from the Catholic saint.

Germany had a similar tradition where a white-clad girl, named Christkind, walked around handing out gifts, as an alternative to the Catholic St. Nicholas. She was dressed in white with a wreath of candles on her head.

The girl was meant to symbolize the baby Jesus and brought with her a boy named Hans Trapp, who was a kind of devil-like figure.

“This German tradition may have been a precursor to the Lucia tradition we find in Sweden,” Baklid says.

Lussi langnatt

Then there’s Lussi from Norwegian folklore. Unlike Saint Lucia, this female figure was not a symbol of goodness and light.

“Lussi was a creature who walked around with a cadre of ghosts. These ghosts were restless dead who arose from their graves in the cemetery,” says Liv Helene Willumsen, a professor emeritus of history at UiT Arctic University of Norway and has studied witch trials in Finnmark and Scotland.

Along with her fearsome entourage, Lussi wandered around on the night of December 13, which was also called Lussi langnatt (Lussi long night), to check to see if people had finished their Christmas preparations.

“She checked on work that was being done in homes, especially anything associated with circular motion, such as spinning, baking and milling, to make sure it was on track before Christmas. If this work didn’t look like it would be done, the household could have gotten some form of punishment,” Willumsen says.

She herself is familiar with the stories about Lussi, and the dead people who rose up from the cemetery, from her own upbringing in Vesterålen in the 1950s and 1960s.

They called this spooky entourage "gangferd" or “gongferd” (a dialect word that roughly translates as the walking dead).

Winter solstice on December 13th

So why did Lussi actually come on the night of December 13th?

“In the Julian calendar, this was the night of the winter solstice, the longest night of the year. It was thought that a passage was opened to the underworld, and it was dangerous for people to be outside,” says Willumsen.

And in Norwegian folklore, it is common for supernatural beings and restless dead souls to appear on important days.

“On days such as the winter solstice, Christmas, Easter and St. Hansaften, the veil between the two worlds is eased a little, so that ghosts and beings from the other side could pass freely, “she says.

In other words, this Norwegian folklore survived for a long time.

Lucia has taken over

But Willumsen acknowledges that Lussi has given way to Lucia, also in northern Norway, where Lussi’s place in the local folklore was once widespread.

“The St. Lucia celebration has taken over. There probably aren’t that many people anymore in northern Norway who are familiar with the details related to Lussi,” she says.

She points out that the white clothes and the lit candles stand in stark contrast to what is the darkest time of the year in Norway, and especially in the north. This has probably contributed to the Swedish tradition having a great impact.

Nowadays, it’s most often children who celebrate Lucia in kindergarten or at school.

Herleik Baklid says that children at the university’s preschool tend to walk in a Lucia parade and sing for the staff at the University of South-Eastern Norway, and that it’s a touching experience.

“I think it’s a good custom that has come to us from Sweden,” says the researcher.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

Skansen: Lucia - a changing tradition, digitalmuseum.se (in Swedish).