Norwegians were intimidated by the labour movement in the United States

The Norwegians emigrating to the United States were Republicans and agreed with the northern states. But the Republican Party was a completely different animal from what it is today.

Almost 800 000 Norwegians travelled to America in the 19th and 20th centuries.

How did they contribute to America becoming what it is today?

What ideas did they bring with them from Norway? What happened to their ideals of equality?

According to historians, Norwegians played a big part creating the spirit of the American people – characterized by taking care of yourself, owning your own land and not depending on anyone.

Emigrated from an overpopulated Norway

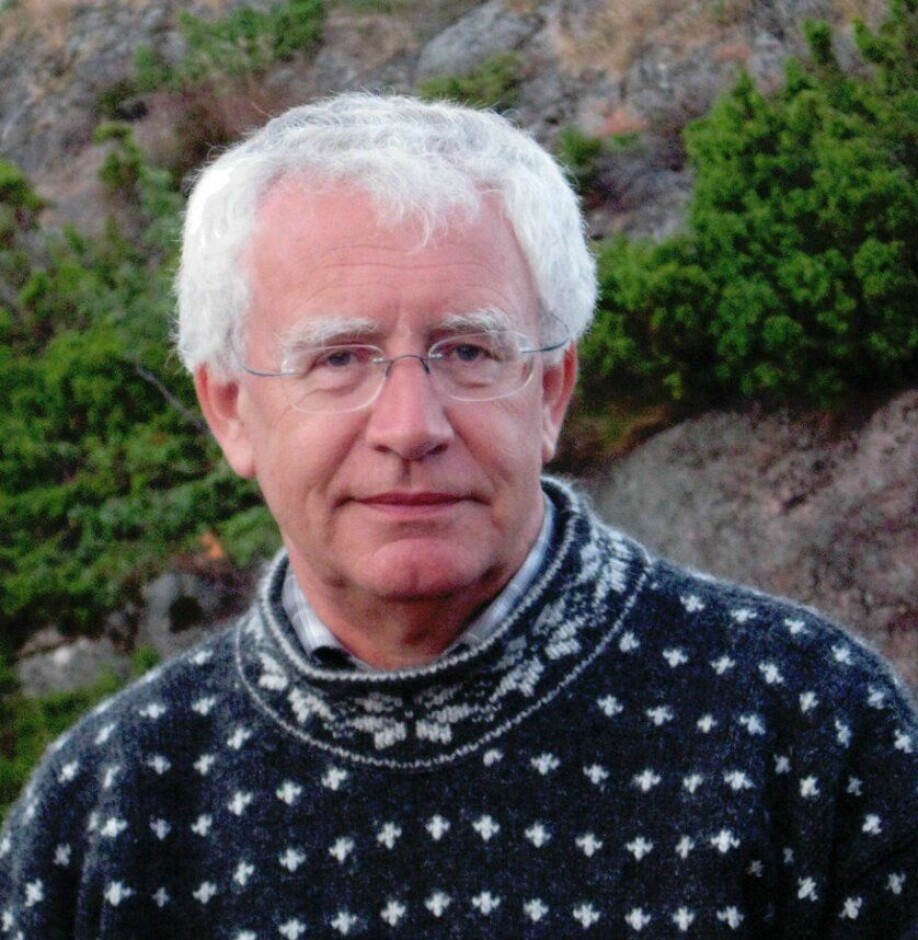

“The number of Norwegian descendants in the US rivals the population in Norway,” says author Sverre Mørkhagen.

Talking about Norwegian Americans as one unified group is no longer really possible.

But it is possible to say something about the political beliefs of the first Norwegians who came to America.

Although the labour movements had just begun to make their presence felt in Norway in the middle of the 19th century, this was still a foreign concept for the vast majority of Norwegians who emigrated to America.

“When they came to the USA, Norwegian immigrants were generally sceptical of the growing labour movement there,” says Mørkhagen.

Those who emigrated to America in the 19th century were leaving an overpopulated Norway. People were primarily concerned about the possibility of a creating a future for themselves and their families, especially for the new generations that were growing up.

“Norway was no longer able to handle the large family sizes. There was simply no room for them, either in terms of places to live or ways to make a living,” says Mørkhagen.

He has written three books about Norwegian emigration to America and is a former journalist and publisher.

Broods of ten caused trouble

The problem of overpopulation was greatest in the Norwegian villages. The agricultural property inheritance law was strictly observed. This meant that family farms could not be divided, and only the oldest son could inherit the farm.

The farms were also too small to be divided into ever smaller parcels.

What could parents offer the rest of their brood of ten children?

“The Allodial Rights Act was sensible in this respect, but it imposed strict limits on how many people the country could feed. We need to remember that Norway had the fastest growing population in all of Europe during the 19th century,” says Mørkhagen.

It was becoming less common to lose young children due to cot death or other typical childhood diseases, and infant mortality dropped drastically throughout the 19th century.

Hopelessness for new generations

“Instead of eight out of ten children dying, as they statistically did at the beginning of the century, all the children started growing to adulthood the closer they got to the 20th century. Then there wasn’t a means of feeding everyone. At first, boys without the right of inheritance became homesteaders, but gradually their homesteading possibilities diminished as well, and new generations increasingly sank into hopelessness,” says Mørkhagen.

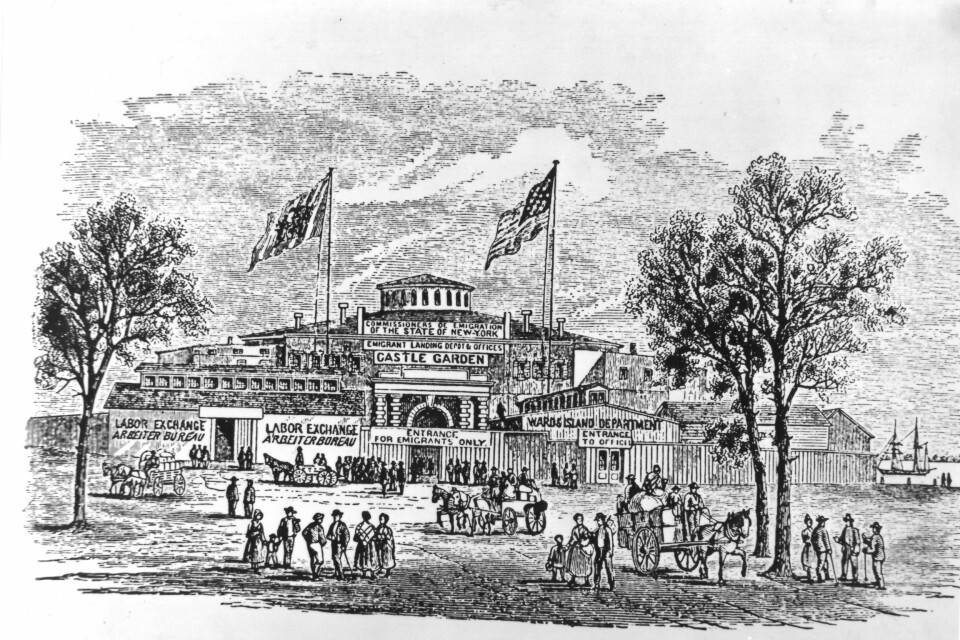

For many, going to America became the only solution, and Norwegian emigration began earlier than it did in most other European countries. The very first, relatively few Norwegian immigrants arrived as early as 1825. The rest came in waves, starting with the first between 1866 and 1873.

Norwegian men had a single goal

Typically, family fathers with their own farms emigrated to begin with. They weren’t among the very poorest in the population and were able to come up with the resources needed to emigrate.

“These emigrants were future-oriented and seized the opportunity for their large number of children,” says Mørkhagen.

The men sold their farms, took the whole family with them and sailed across the sea to the promised land, so that all their children would have a future.

“When they arrived there, their one overriding consideration was to acquire land,” Mørkhagen says.

At home in Norway, they had learned how important it was to own their own land, which always provided opportunities to make a living.

“Property ownership was the life insurance they were looking for,” says Mørkhagen.

Scary ideas – for Norwegians

Gradually more immigrants came from ever more different countries in Europe. For them, land and property were less important, and many of them began to work in growing industries in the larger cities.

Workers also began to organize to secure the best possible working conditions. In Europe, socialist ideas of community and unity had begun to take root, and soon these ideas caught on among American industrial workers as well.

One of their central political ideas was that property should be held in common, and belong to society and not the individual.

“This concept sounded frightening to those who had just managed to acquire their own land, which was typically the Norwegian settlers' main life insurance,” says Mørkhagen.

Reacted to poor working conditions

While Norwegians travelled from Norway in a very poor period in Norwegian history, they arrived in a rather radical period in America.

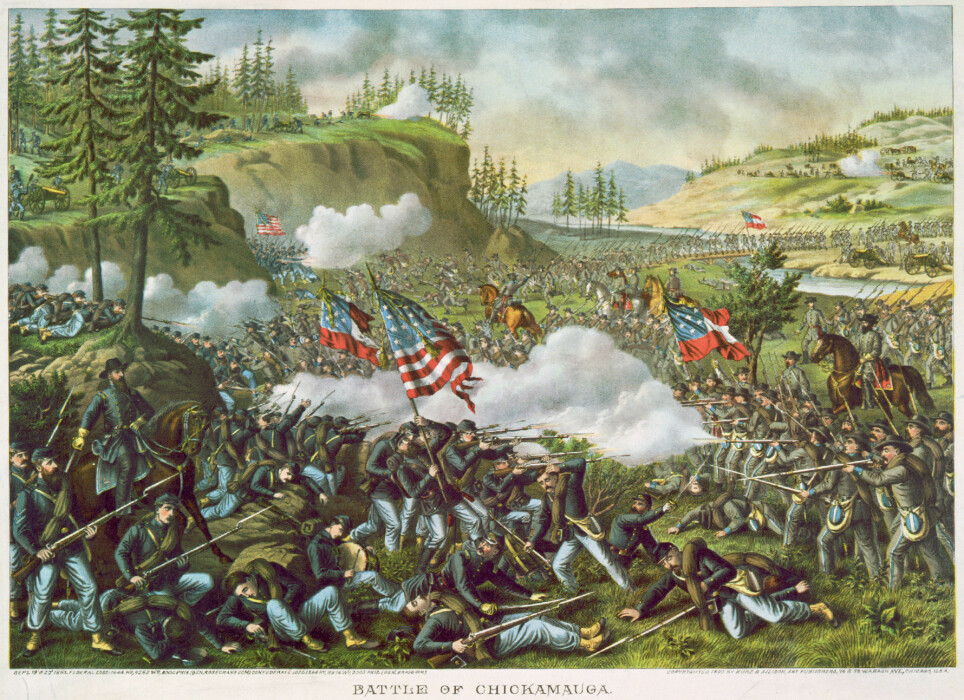

Not only did they come just before, during, or right after the American Civil War. They also came as large-scale railway development was making its way across the American continent.

The railroads were of great importance to the Norwegian landowners who followed the settlements westward.

“The railway development was a double-edged sword, where the federal authorities gave large areas to railway companies,” says Terje Mikael Hasle Joranger, a historian and department director at the Norwegian Emigrant Museum.

Joranger says that a number of Norwegians feared that the properties – which they had just acquired – would be handed over to the railway companies.

“A lot of the socialist thinking in the Midwest arose as a reaction to railway construction. What they had in common with the Norwegian landowners was that they were against the government giving the railroads so much power,” says Joranger.

So even though Norwegian settlers were sceptical of socialism and the labour movement, they still fought against capitalism and market forces.

Concerned about workers and solidarity

Joranger has researched Norwegian immigration and adaptation in the USA and recently published a book on the topic.

He notes that despite the fact that Norwegians were concerned about their own property, they also stood in solidarity with industrial workers.

“The support revolved aroung protecting the poor and defenceless, as well as regulating the power of big business empires and preventing the amassing and abuse of power and money among the few,” says Joranger.

According to Joranger, Norwegians had a strong sense of justice. They were egalitarian and opposed exploitation and believed everyone should have the same access to good economic conditions.

“Many people supported socialism in Minneapolis and the neighbouring city of St. Paul in the 1890s, but it was social democratic principles rather than a belief in revolution that won out,” says Joranger.

Started organizations and created schools

Nearly 800 000 Norwegians sailed to the United States between 1850 and 1920, almost a third of Norway's population at that time.

According to Joranger, the emigrants brought many basic Norwegian ideas with them, such as hard work and volunteerism, equality and a good work ethic.

“These were qualities that matched the values appreciated by the American elite, which made it easier for Norwegian immigrants to be considered ‘good Americans’ in their new homeland,” says Joranger.

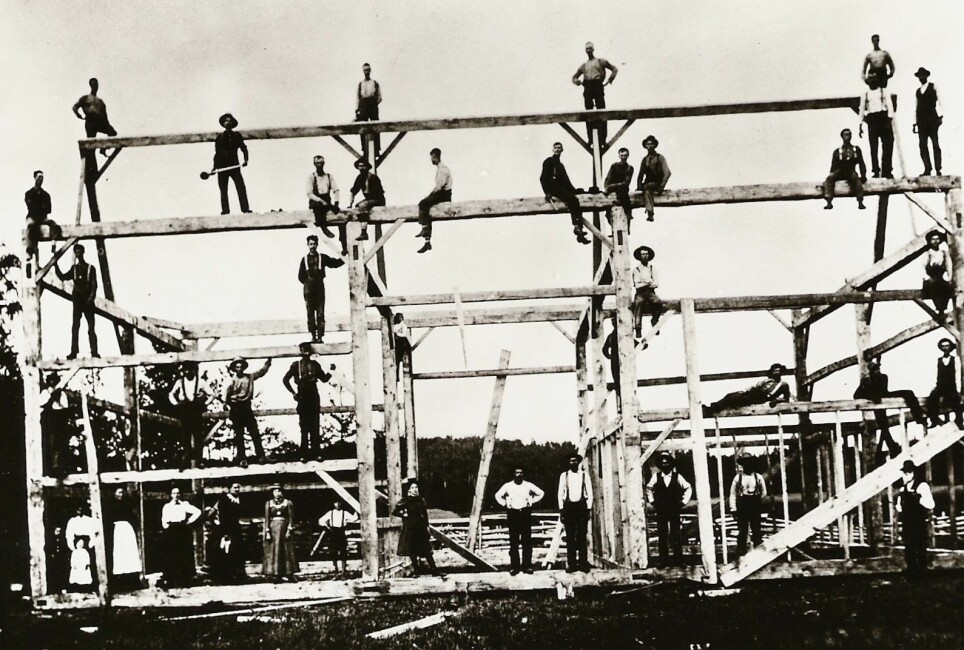

“The Norwegian immigrants developed a strong organizational life when they arrived,” he says.

Norwegian pride

According to the Norwegian Emigrant Museum, many Norwegians were proud to be Norwegian-Americans, especially in the period between 1895 and 1925.

During these years, large Norwegian-speaking groups in the cities and in the countryside organized themselves into various associations and unions.

In rural areas, their gathering centred around community activities.

In the cities, on the other hand, a number of entertainment associations, choirs, sports clubs, folk dance groups, religious associations, as well as political groups and trade unions appeared.

Impressed with American democracy

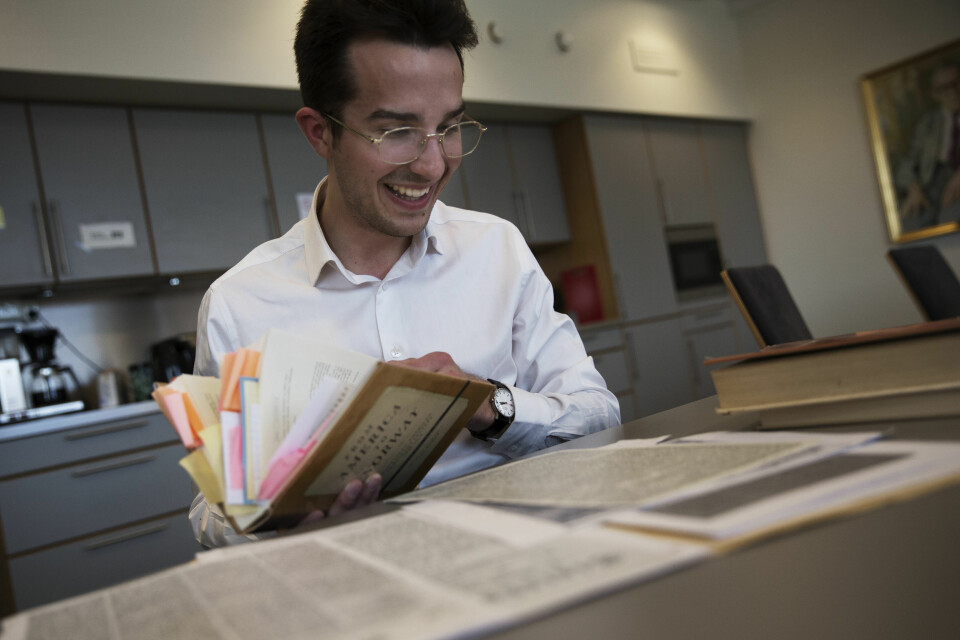

Henrik Olav Mathiesen is a researcher at UiO’s Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History.

He previously researched Norwegians' affiliations in the Midwest.

The Norwegians had a lot to learn from American society, according to Mathiesen, and many were impressed by the new republic with the right to vote for all.

No universal suffrage in Norway existed at the time the Norwegians travelled to the United States, and the country was ruled by the Swedish king.

“A number of workers in the Thranitter movement – Norway’s first labour movement – emigrated, including Marcus Thrane himself. Many attitudes expressed in the labour movement's newspaper can also be found in American letters before and after this movement, according to Mathiesen.

The UiO researcher has studied letters that were sent from America to Norway between 1830 and 1860.

Critical of class society in Norway

“These early American letters give an impression of a critical attitude towards the class society and the government in the home country,” Mathiesen writes.

Some of the letters include descriptions of the broad political participation in America.

Some of these can be understood as an implicit critique of the lack of similar opportunities in the home country, according to Mathiesen.

As is well known, the right to vote in Norway was more limited than in the United States, and many emigrants were impressed by the popular and egalitarian nature of American society.

An emigrant wrote home in 1837 that “[t]he people elect all the government officials, of whom the supreme one is called the President and is elected only for 4 years, and when they no longer want him as such they choose another and then he is not considered higher than any another worker, which shows that here there is no difference between the poor or the rich, if one simply behaves well, and the people consider him capable and choose him, and thus everyone has the right to become a person of authority.”

“To read something like this in Norway in 1837, which at that time was largely a pre-industrial class society with a king who ruled from Sweden, must have been as exotic as to read another description in the same letter of how ‘[o]ne travels through the land with wagons that go by steam,’” writes Mathiesen.

The American spirit was born on the prairie

Sverre Mørkhagen wrote Drømmen om Amerika (The Dream of America) in 2012. He believes that the Norwegians played an active part in forming the spirit of the American people.

This folk spirit established itself in the settlements on the prairie, where there was no infrastructure, no military, no police authority, no one to make sure that law and order were observed. All this came later.

“Children learned growing up that the only defence you have is the defence you can provide for yourself. And they took this belief into their adult lives,” says Mørkhagen.

“You had to be ‘self made’ and manage things yourself, because you had no one else to trust. This belief is deeply ingrained in Americans to this day. It affects large parts of the American population and will probably do so for many generations to come,” says Mørkhagen.

To this day, the Norwegian descendants are among those who have remained in more rural areas to the greatest extent.

“This helps explain the fact that Norwegian Americans are loyal and usually vote for the Republican Party. They are the ones who set the tone on the American prairie, Mørkhagen says.

Translated by: Ingrid Nuse.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no.

Reference:

Terje Joranger et al: Nordic Whiteness and Migration to the USA. A Historical Exploration of Identity. Routledge. ISBN 9780367277185. Summary (publisher)

Sverre Mørkhagen: Det norske Amerika. Gyldendal. 2017. ISBN: 9788205508309

Sverre Mørkhagen: The dream of America – Immigration from Norway 1825-1900. Gyldendal. 2021. ISBN: 9788205508293