Medieval scribes wrote about religion, medicine and magic in the margins

Ildar Garipzanov has gone through several thousand manuscripts from the Middle Ages in search of the smallest texts.

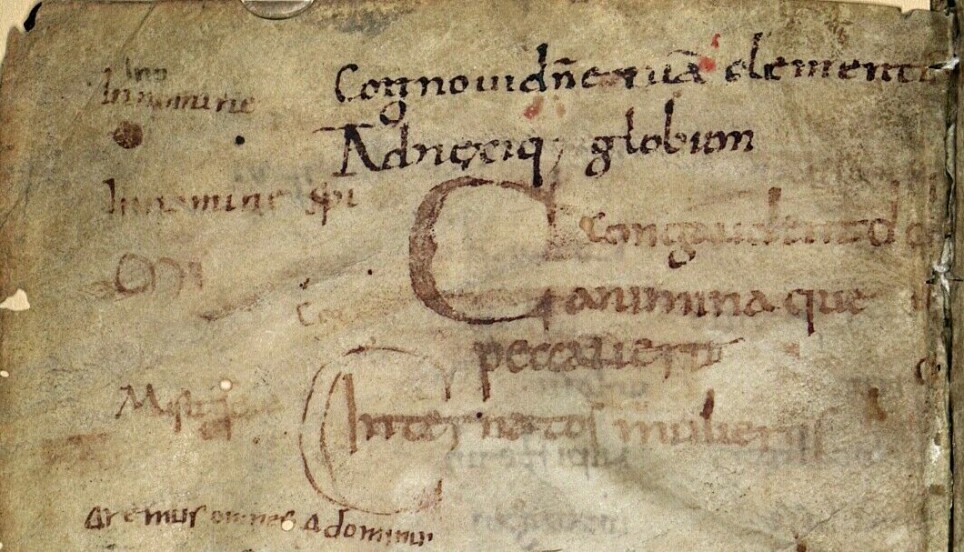

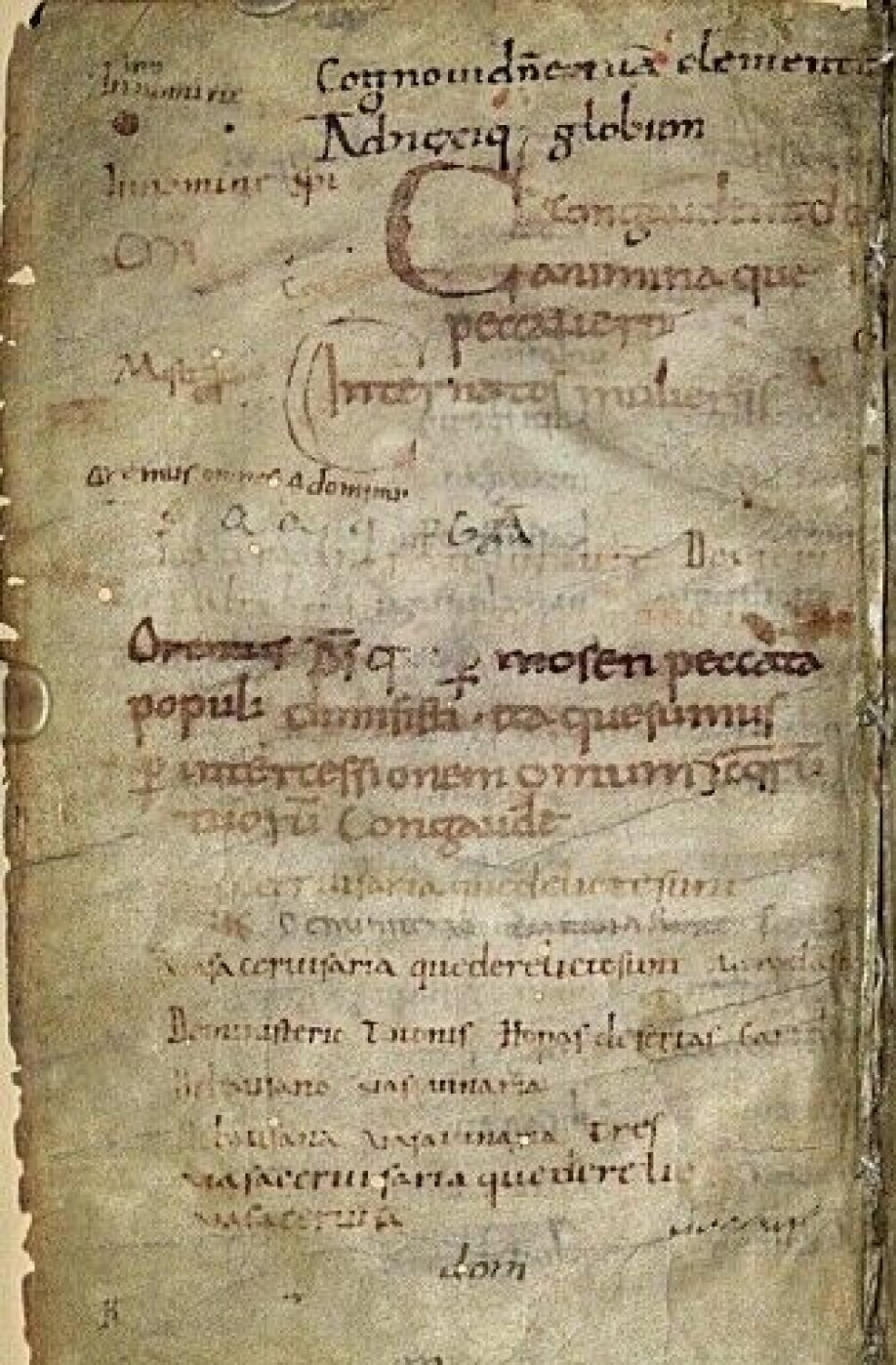

Many of them have been written off as scribbles to check that a pen worked. As a result, no one has studied them properly. But hidden in front, behind and between the lines of 1,300-year-old manuscripts are hitherto unknown glimpses into everyday medieval life.

“Researchers have never studied these texts in the systematic way that I am trying to do now,” said history professor Ildar Garipzanov at the University of Oslo. His subject of study is what are often described as probatio pennae - pen tests.

Blank pages

They are there simply because whatever was written down in the years 700 to 1,000 typically came with a couple of blank pages in front and at the back of the manuscript itself. These pages helped protect the actual contents of the manuscript from moisture and wear.

At a time when paper had not arrived in Europe and the skin of 70-100 sheep might be needed to produce a single parchment manuscript, it’s not surprising that blank pages and blank areas were used when there was a need to write something down.

“When we look at these texts, we can say something new about early medieval culture,” Garipzanov said. He estimates that a review of the approximately 9,000 European manuscripts that have been preserved from before the year 900 will give him several thousand short texts that have never been studied before.

Knowledge and religion

“This is not just about analysing manuscripts and drawing broad assumptions. The project will also say something new about early medieval culture,” he said.

So far, he has found four different types of texts that monks, priests and other scribes have written in the margins and the blank pages of the manuscripts. They have written down practical information, practical liturgy, and information about magic and medicine. Often the themes were mixed together: In these times, there was a short distance from religion to magic or from religion to medicine.

“The practical information was of a type that was important for the monastery and the cathedral in relation to the outside world,” Garipzanov said. He described an example where the monk who was responsible for the finances of a monastery wrote down how much winter grain the monastery's pig farmers were given to feed their animals until spring.

The liturgical notes can provide new knowledge about when different rituals entered church practice. Until now, researchers have looked at formal, or normative, texts. In practice, much had been developed 100 to 200 years before these practices were mentioned in these texts, simply because the pastor needed to plan his next service.

God and demons

Religion and magic have often been studied separately. In reality, the connection is clear in the Middle Ages. Several short texts describe magical incantations. They invoke the god of Christianity in the fight against demons and evil forces which don’t belong at all in the correct teachings of the church.

Garipzanov described a manuscript from the ninth century that actually contains laws from Lombardy, in today's Italy. On the last page, there are small descriptions of things that the Church Fathers had actually forbidden — about how Coptic, occult characters could be combined with prayers to God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit to make an amulet that could protect against evil forces.

Magic and medicine

Medicine was also mixed with religion and magic in a healing culture. An illness was often perceived as being linked to evil spirits, and it was important to know the right spells to chase the evil spirit out of the body.

“Compared to literary sources, these texts tell a different story about how people lived. At this time, the average lifespan was 40-50 years, and people died early of various diseases,” the University of Oslo professor said.

He sees a parallel in the fact that many in Norway believed in huldra (seductive forest creatures), fjøsnissen (a cowshed elf) or dark angels a thousand years later, at the same time as they saw themselves as Christians.

“The question was how should one fight these evil forces? In the normative texts you only have to preach to the Christian God or saints. These texts speak directly to evil forces and supernatural beings. People cared most about being healed; it was not so important where the healing came from,” Garipzanov said.

Curses for book thieves

While the early Middle Ages are fertile ground as far as the brief messages on empty spaces are concerned, other researchers have looked at what has happened with texts in later books and manuscripts. Before correction fluid and backspace keys, written errors were often preserved.

"Because books were expensive, no writer would throw away a book unless the damage was very serious," Deborah E. Thorpe of the University of York told BBC History Magazine.

Many book owners took the opportunity to write in their manuscripts a small curse that promised torture, death and/or eternal damnation to anyone who tried to destroy or steal the book.

Cat prints across pages

Emir O. Filipović was working on his doctorate at the University of Sarajevo when he found some completely different evidence in a book. He discovered how a cat in Dubrovnik in the 14th century had first stepped into an inkwell and then walked over a few pages, according to an article in Smithsonian Magazine.

Because parchment was expensive, it also happened that old texts were effaced to make room for new ones. A page from the Qur'an from the eighth century, for example, turned out to be written on what was previously a page from the Bible, more specifically from Deuteronomy.

“This is a very important discovery and a proof of cultural contact between different faiths,” said Qur’an expert and postdoctoral fellow Éléonore Cellard at the Collège de France to the newspaper The Guardian.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

Ildar Garipzanov: Magical Characteristics in the Carolingian World: A Ninth-Century Charm in MS Vat. lazy. 5359 and Its Broader Cultural Context. Speculum, April 2021, doi: 10.1086 / 713057. Summary.

———