The nightman emptied the toilets of the city in the 17th century. It was dirty work, and his kids were considered dirty too

“Working as a nightman was one of the few ways you could be pardoned and escape the death penalty,” says historian Ragnhild Hutchison. She's not sure it was a better option.

The largest towns were growing, and the outdoor privies were overflowing. In Norway, the nightman role came into being in the 17th century. His job was regarded as without honour and filthy.

“Nobody wanted to go into a nightman’s house. People believed he was contagious. It was a pariah job,” says historian Ragnhild Hutchison.

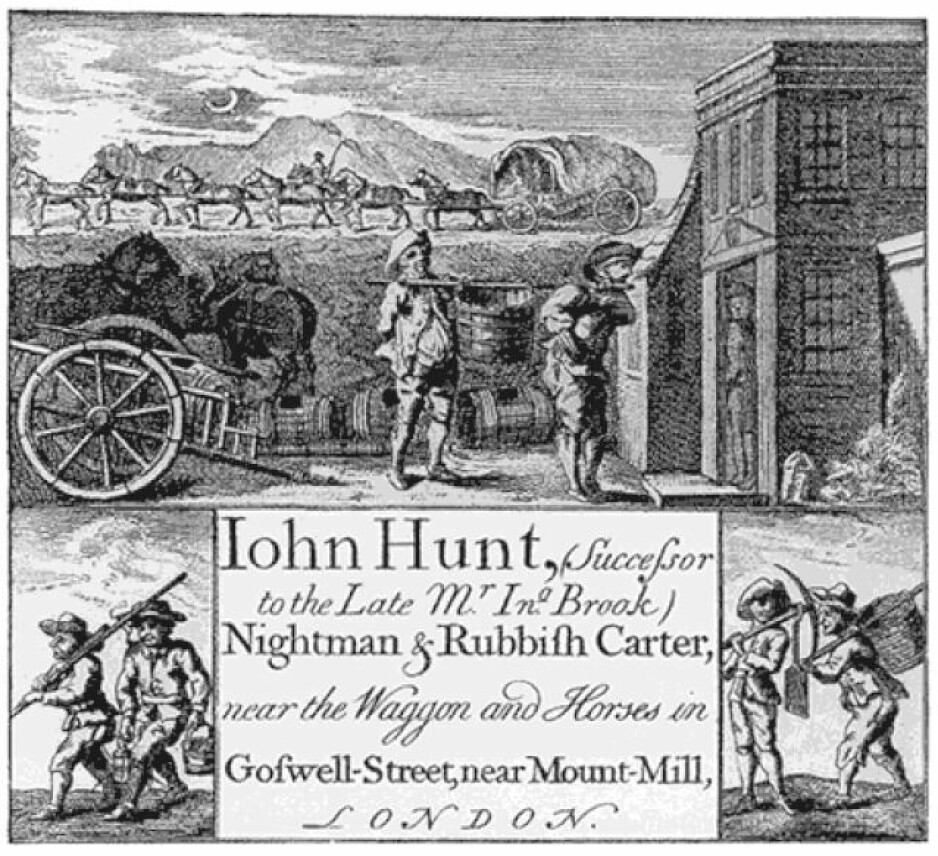

The word ‘nightman’ indicates his working hours, which were carried out after dark to minimize the nuisance.

The nightman was also called a rakker in Norwegian. And a rakkerunge was the child of a nightman. Calling someone a rakkerunge was eventually banned by the king.

Used nowadays, rakkerunge means a little rascal or scoundrel.

Only way to escape beheading

The Norwegian encyclopaedia (Store norske leksikon) writes about nightmen that the job’s low status ‘speaks for itself’. Why does it speak for itself?

Nightmen emptied privies and cleared dead animals from the streets. It sounds like an honest and important job – even if not everyone would be well-suited to do it.

But becoming a nightman was not a career choice, nor a job you happened to have because you couldn’t find anything else to do.

“Nightmen were murderers or serious criminals. Working as a nightman was one of the few ways you could be pardoned and escape the death penalty,” says Hutchison.

Hutchison admits she’s not sure being a nightman was the better option.

Not considered important

The privies in then-Christiania (now Oslo) would have overflowed if it had not been for the nightman. However, that did not affect his low status, according to Hutchison.

“The job wasn’t considered important at all. It involved human waste and was considered one of the worst jobs you could do. No one else would do it except for men who were convicted and sentenced – mostly to death.

The nightman would take his horse and cart out on his regular route to the town living quarters. He took out the privy buckets one by one, emptied them into the cart and rolled on to the next location.

Sometimes dead animals, like cats or rats, littered the streets. He picked them up and took them with him, too. He also had to take care of people who had committed suicide.

From there he transported the cart contents to the place where we today find the Oslo City Hall - and dumped it in the fjord. Eventually the amount of excrement became pretty large.

Hutchison tells of a complaint brought to the Christiania magistrate about the horrible stench – and a prayer that the nightman would no longer need to dump the load right outside his house.

No plastic packaging

You could say that the nightman served as a kind of early waste collection service, since very little other waste than excrement was produced in the 17th and 18th centuries.

“Imagine a world without plastic packaging. People ate all the food they had,” Hutchison says.

“People also ate much less than we do now and had access to fewer foods. They didn’t leave tomatoes to rot in the fridge.”

And if they had other vegetables, they only ate them in season.

“The vast majority of people ate bread and porridge, and they consumed all their food. If they had meat, they ate it down to the bone and then used the bones for soup stock. The bones might then have been discarded – if they weren’t used to make buttons or other such items,” says Hutchison.

Well-worn clothes a resource

People also sold old clothes. Clothes were not thrown away to refresh people’s wardrobes.

“Clothes were only discarded after they had been worn to shreds.”

When clothes were so threadbare that they could no longer be repaired, they were delivered to a paper mill and repurposed into paper.

Manure from animals was also a resource.

“People who had animals where they lived would transport the cow and horse manure out to unoccupied plots to use it as fertilizer there. Some manure ended up in the streets, but not very much,” says Hutchison.

Nightman-children with distinguished godparents

Cultural historian Frans-Arne H. Stylegar wrote about nightmen in Kristiansand on his blog in 2011 (in Norwegian).

It was no simple matter to find godparents so that the nightman’s children could be baptized. Sometimes the city's distinguished citizens had to step up.

When the children of Ole Nielsen and Cathrine Jonsdatter were to be baptized around the year 1800, Councilor Høyer and Mrs. Mørch were assigned to the task.

Had the church records not made clear that it was the nightman and his wife's children being baptized, we could just as well have thought they came from a noble family,” Stylegar writes.

The King forbade namecalling

King Christian V took action in 1685, according to a Facebook post from the National Library of Norway on 28 March.

The pariah status of the nightmen had become problematic, but their work was a compelling need in cities like Christiania. The King of Denmark decided to do his part to clean up the occupation.

He passed a new law that forbade calling the children of nightmen rakkerunger or in general accusing the nightmen of being dishonest.

The 18th century began to generate more disposable trash, says Hutchison. People replaced wooden plates with porcelain and threw more things away.

Then came the 19th century: Christiania’s population tripled and housing construction was not keeping up. A municipal waste disposal system became a necessity, and the nightman went down in history.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no