What old graffiti can tell us about medieval people

In some places, the carvings are a sign of religious community. On other walls, they are a product of competition.

Graffiti is not a new phenomenon.

People have left behind traces in the form of carvings and paintings since time immemorial. The graffiti has taken on new forms. But maybe the reason for tagging something is the same now as it was 1000 years ago?

What medieval people have carved into walls and surfaces can tell us something about who they were. What were they thinking and feeling – and what did they feel a need to express?

Church and non-church graffiti

Runologist Karen Langsholt Holmqvist has been researching self-perception in the Middle Ages in her doctoral work – with ancient graffiti as her starting point.

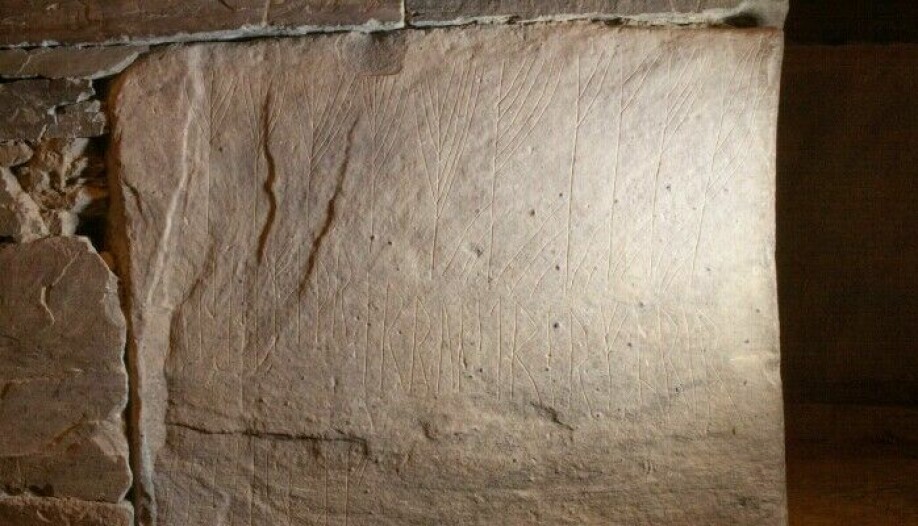

Holmqvist, who now works as a consultant in the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage, has examined runic writing in several medieval churches, including the stave churches Hopperstad, Borgund and Gol – the last one at the Norwegian Folk Museum in Oslo.

“In churches, people often connect to the place by writing their name or prayers for themselves or others. The messages express affection,” says Holmqvist.

She has also looked at graffiti outside the church context in both Norway and Scotland.

Local stories and myths

Holmqvist found one example of landscape graffiti in a so-called saint's cave in Scotland. The second example is a stone age burial chamber on the Orkney Islands off the coast of Scotland. The third is a rock wall on a hill above Stjørdal in Trøndelag.

In the burial chamber on the Orkney Islands, people have broken in and filled the walls with graffiti. In the saint’s cave, Norwegians probably stopped by and left their mark. The rock wall in Stjørdal might have been a landmark in ancient times, such as a separation between two farms.

The non-church context often involves myths related to the place. Stories – local myths – of treasures hidden under a rock or inside the cave abound.

“If you go for a walk in the woods with an older person who knows the area, you can hear stories like this nowadays as well,” Holmqvist says.

Community and competition

The graffiti varies from place to place. In churches, graffiti is often more personal than landscape graffiti.

“Even though they’re similar to each other, the inscriptions show that the individuals who carved were connected to the church and wanted to be part of the religious community.”

The Maeshowe burial chamber in Scotland conveys other things.

“There we see inscriptions where the carvers competed to create the most impressive inscription,” Holmqvist says.

For example, runes were carved as high as possible on the wall. Maybe the graffiti artist had to stand on someone's shoulders to make it happen? It’s clearly not randomly placed.

And then there were carvers who used cryptic runes. They simply created their own rune system, she explains.

Bringing the spray can to the church would probably not be very popular in our day and age. But was it illegal to leave your mark in Gol Stave Church a few hundred years ago?

“We have nothing to indicate that it was illegal,” says the researcher. It also appears that some priests took part.

Toilet graffiti

As a student in Trondheim, Holmqvist’s research included the campus. She found toilet graffiti, and this too has been given a small place in Holmqvist's dissertation.

Even people who make non-church graffiti in the 2000s are still strongly connected to place, she says.

"Stories were made up about a small door that was a little strangely placed in one of the toilet stalls and where the door might lead. And if you flushed yourself down the toilet, you would end up in the Ministry of Magic in the Harry Potter movies. Here you can clearly see how place is connected to modern stories that live in the present time", Holmqvist says.

Tourists like to leave traces

In recent times tourist graffiti has become popular. Examples can be found everywhere from Eidsborg Stave Church to Nidaros Cathedral and the Acropolis in Athens.

Holmqvist believes that we can compare the new graffiti with church graffiti from the Middle Ages in the way that people want to connect themselves to a particular place.

“They come to a place that they think is really cool, and want to leave proof that they were there.”

In the Middle Ages, people probably had a slightly stronger religious motivation when they left their name in a church, she adds.

“But the inner motivation to do so may be similar – whether it’s religion or fascination with medieval culture,” Holmqvist says.

What did people write on pub walls after a few beers?

Holmqvist believes we can learn a lot about what people thought, felt and were interested in during the Middle Ages by looking at their ancient graffiti. Still – what we have left is only a small fraction, and what remains is probably not representative of everything that once existed.

Holmqvist believes there might have been a lot of interesting material in city buildings that have not been preserved.

“It would have been interesting to know what people wrote in the city pubs. That hasn’t been preserved, so we don’t have the full picture of what people were interested in at the time,” she says.

We know a fair bit about what life was like from the old sagas. But they were written in monasteries by highly literate people. The runes were written by a wider cross-section of the population.

“Inscriptions, especially in the churches, reflect that society was much more religious in medieval times.”

Some are quirkier than others

The researcher has discovered that some inscriptions are easier to interpret than others. Sometimes one crops up that is really cryptic, a bit mysterious or that can be interpreted in different ways.

'Do not hurry,' the small runes over the choral door in Gol stave church advise. Interpret that as you wish.

Do we sometimes forget how poetic or intellectual people in the Middle Ages were?

“Some people were highly literate and intellectual and played with different forms of expression and ambiguity. And then there were others who weren’t so literate, whose inscriptions contained several errors,” Holmqvist says.

And while some of the inscriptions were probably meant to be mysterious, in other cases the context has been lost and makes them impossible to interpret today.

Based on what she’s found, Holmqvist thinks people weren’t that different from us even when we go back several hundred years. But society has probably changed a little. We are clearly more liberated from religious norms today.

“The inscriptions still show that people are more alike than you might imagine,” she says.

- RELATED: Was rape common in the Middle Ages?

Could be vulgar then too

Like modern toilet graffiti and illegal street graffiti, the graffiti of the past could be pretty vulgar.

A lot of ancient graffiti can be found in the city of Pompeii, including penis drawings and mudslinging.

'Chie, I hope your hemorrhoids rub together so much that they hurt a lot more than ever before!,' is one of many examples.

“When it comes to the written scribblings, you can find everything from the usual 'NN was here,' to declarations of love, political agitation and product marketing,” historian Jon Iddeng at the University of Southeast Norway said to forskning.no.

He believes most of it revolved around a need to be seen and heard.

“People are people. Back then just like now. They probably had the same need to express themselves just like we do, only not with Facebook or Twitter,” Iddeng said.

Reference:

Holmqvist, Karen Langsholt. (2021). Carving the Self: Portrayals of the Self in Medieval Textual Graffiti from Norway and Connected Territories. Doctoral dissertation, Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research and the University of Oslo.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no