Almost 40 glaciers on Svalbard have woken up

After many years of "sleep", these glaciers are now advancing at full speed.

Last winter brought little snow to Svalbard.

Then the summer brought record heat.

As expected, this led to the loss of mass from a number of glaciers on Svalbard, and several glaciers retreated.

At the same time, a number of glaciers are now experiencing a special phenomenon that glacier researchers call a surge.

These are glaciers that have lost a lot of mass — but where the glacier front is still rapidly moving forward. Many of these glaciers have woken up after 50 to 100 years of "sleep".

Four glacier researchers reported the phenomenon in an article in Svalbardposten (link in Norwegian), which was quoted by the website geoforskning.no.

Dangerous glaciers

“There are a lot of surging glaciers on Svalbard right now,”says Jack Kohler.

Kohler, a senior researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute, warns that these glaciers can be particularly dangerous for people travelling on Svalbard.

“The scary thing about surging glaciers is that they can appear to be safe, over many decades. Then they begin to advance,” says Kohler.

“Then dangerous crevasses can appear in places where snowmobile riders and skiers have not seen them before.”

An even greater danger is if the crevasses are buried and invisible under snow bridges. Whether or not the snow bridges are strong enough to support a snowmobile or skier depends on both the amount of snow and how well the snow cover has settled.

Can move very fast

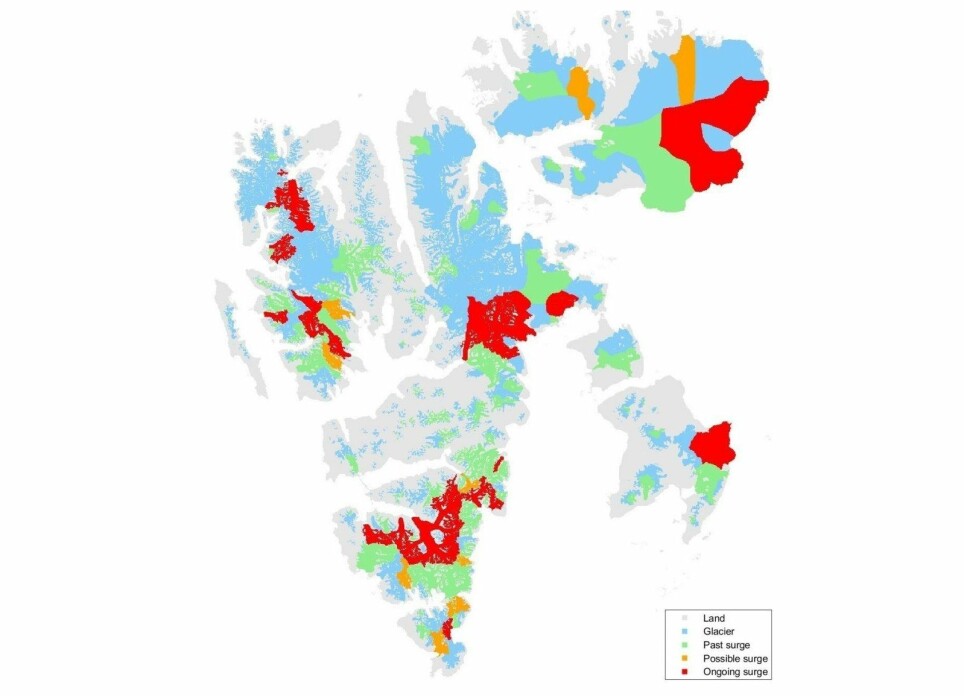

Satellite images show that almost 40 glaciers on Svalbard are now in a surge phase.

Another 11 glaciers show signs of surge activation, including the well-known Kongsvegen near Ny-Ålesund.

At its fastest, a surging glacier can move tens of metres forward in one day.

The glaciers on Svalbard are known for having been "asleep" for a long time. The usual periodicity is 50 to 100 years, after which they can begin to surge for several years.

Growing and shrinking

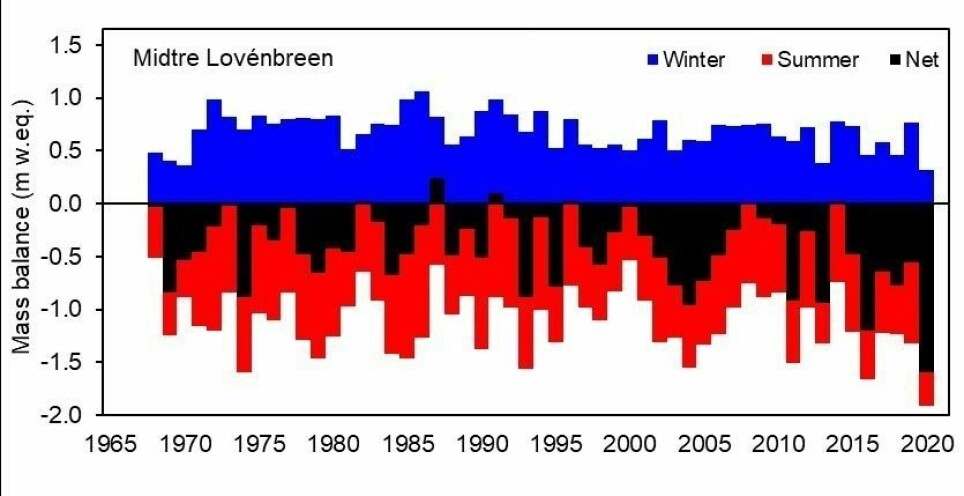

The glaciers on Svalbard grow in the winter and shrink in the summer.

The sum of this growth and shrinkage is called the glacial mass balance.

Since the mid-1960s, the Norwegian Polar Institute has measured this process, and now has one of the longest such time series in the world. This is how researchers were able to see that the glaciers they have monitored have melted more than usual in recent decades. This is completely in line with what glacier researchers are seeing elsewhere in the world.

Climate change is undoubtedly the most important cause.

Cause unknown

But the cause of increase in dangerous crevasses in Svalbard’s glaciers is due to more than increased summer temperatures.

“Surging is also a cause,” Kohler says.

The researchers don’t know for certain whether or not the phenomenon of surging is linked to warmer temperatures on Svalbard. They also don’t know much about why glaciers may suddenly accelerate in the future, as almost 40 Svalbard glaciers do now.

“What we know is that something must happen to the water at the bottom of the glacier,” says Kohler.

“We are convinced that it has something to do with the water pressure on the underside of the glacier. But we need to do more research to find out. Today we are without any definite explanation.”

The increase in the supply of meltwater causes the water pressure to rise below the glacier. Most glaciers experience this meltwater increase in the summer.

“We believe a surge occurs when the drainage of water under the glacier, doesn’t work properly,” Kohler says.

“Something happens in the interaction between the ice, the water and the sediments on the underside of the glacier, which can make it move forward much faster than before.”

Initiated research project

Glaciologists from the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Polar Institute, along with several other Norwegian and international research institutions, are now starting a research project called MAMMAMIA.

The name is an acronym for Multi-scAle-Multi-Method Analysis of Mechanisms causing Ice Acceleration.

The researchers have received what is called free project support from the FRIPRO programme, from the Research Council of Norway. The project support will allow them to sink instruments into the glacier ice to study the surge phenomenon.

The researchers hope that MAMMAMIA will help them learn more about the poorly understood ice surges on Svalbard.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

———