The famous Jutulhogget canyon was created by a megaflood

The megaflood, which occured 10,400 years ago, must have been a disaster for the first people living in the area.

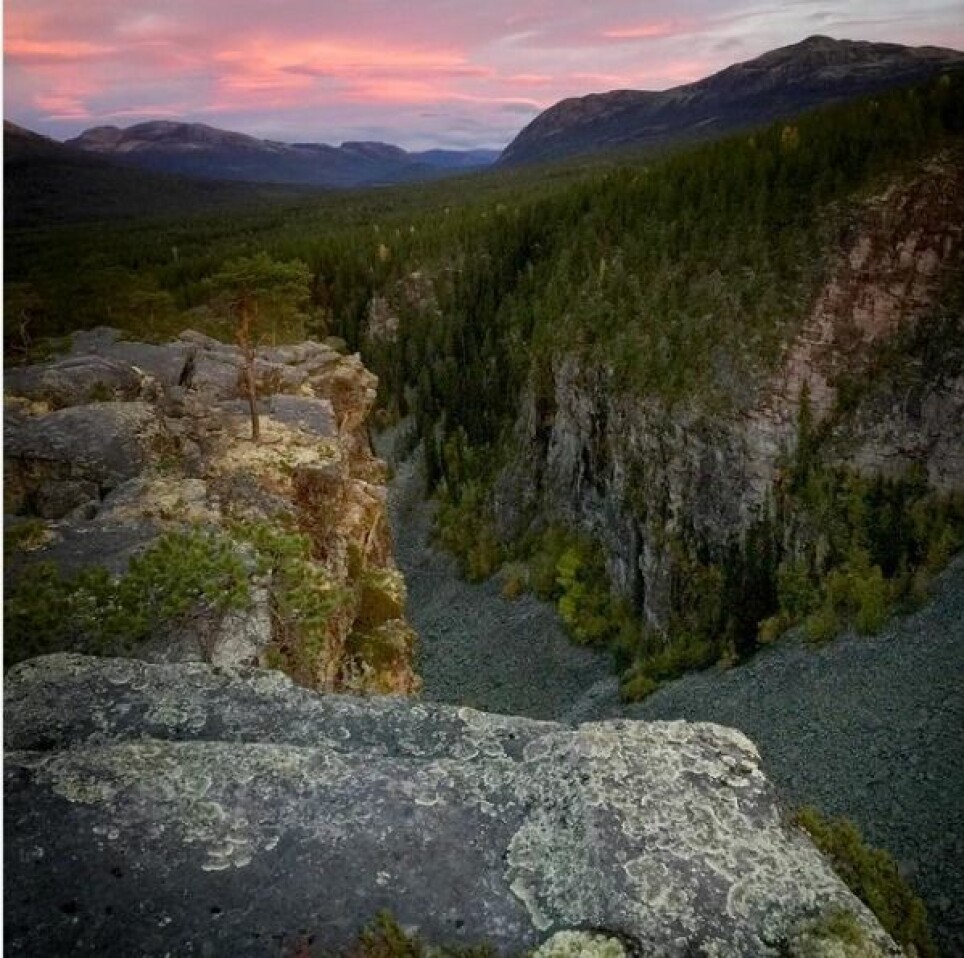

If the saga has it right, Jutulhogget canyon came to be when the Rendalsjutulen troll cut the steep-sided gorge between Rendalen and Østerdalen valleys in south-central Norway.

But researchers are now pretty sure a megaflood was the cause of the landform.

The water volumes were much larger than researchers have previously believed, a new study concludes.

In just a few days, several hundred thousand cubic meters of water per second were able to excavate what is now Northern Europe's largest canyon.

Much larger than expected

As early as the end of the 19th century, the geologist Andreas M. Hansen suspected that terraces in the terrain at the top of Østerdalen and Rendalen valleys and further up towards Røros could be old shorelines along the edge of what was once a large lake.

Geologists have consequently long known about the great flood that occurred when this large lake — named Nedre Glomsjø — flooded south at the end of the last ice age, after a "plug" in the ice barrier had loosened.

The megaflood that resulted excavated Jutulhogget, one of Norway's strangest geological phenomena, between Rendalen and Østerdalen.

Incomprehensible water levels

Researchers have now re-evaluated their calculations.

The calculations show that the flood that washed over Østlandet may have had a maximum size of 1 to 1.5 million cubic metres of water per second, as it passed the town of Elverum.

For comparison, Norway’s Glomma River, which runs past Elverum, has an average water flow of 705 cubic metres of water per second.

“This was a significantly larger flood than previously thought,” said Fredrik Høgaas, a researcher at the Geological Survey of Norway (NGU). Among others, Katherine Aurand at Sweco helped Høgaas with the new calculations.

A mega flood

The researchers mapped a lot of exciting geology in Østerdalen and Rendalen as part of their project.

Among other things, they have figured out how high the flood water actually was in the Østerdalen valley, Høgaas said.

The floodwater elevations helped researchers understand how much water was actually involved.

“The energy that was released was far beyond our comprehension,” Høgaas said to sciencenorway.no.

The NGU researcher admits he thinks it’s amusing to be able to say that the flood from Nedre Glomsjø is considered by researchers to be a megaflood — which is a flood with flows of at least 1 million cubic metres of water per second.

Four times the size of Lake Mjøsa

Nedre Glomsjø was by far the largest of several lakes in Norway that had been dammed by ice at the end of the last ice age.

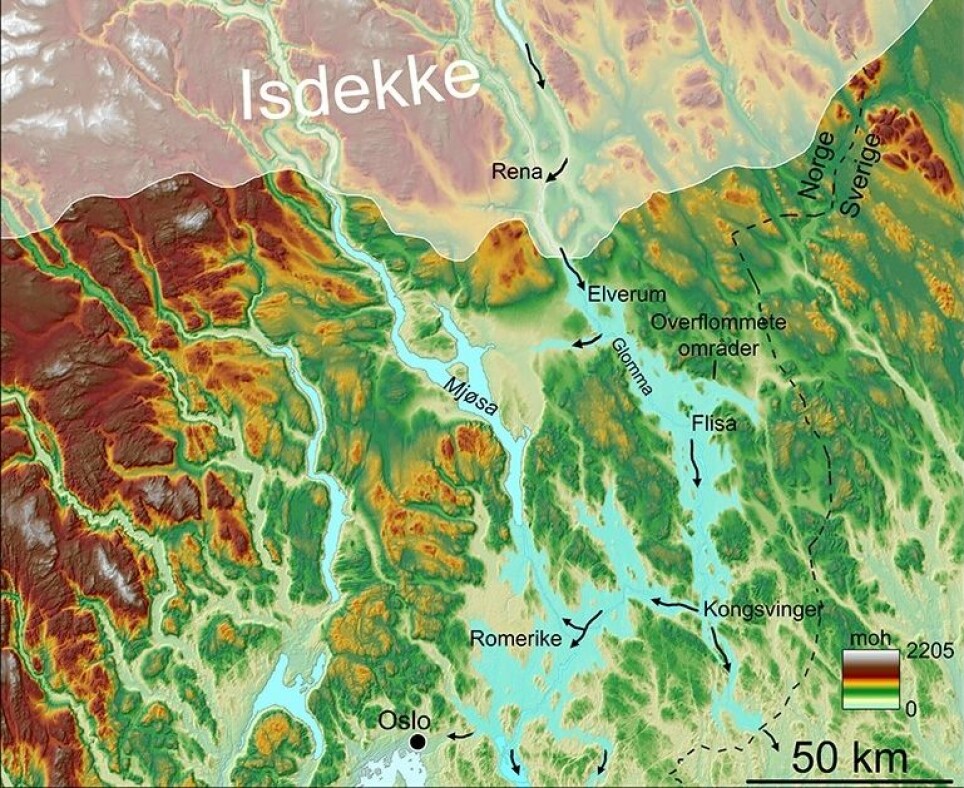

This giant lake stretched from Åkrestrømmen and Atnosen in the south, to Rugldalen in the north, where its outlet was towards Gauldalen.

The surface area of the Nedre Glomsjø lake was four times as large as Norway’s largest lake today, Lake Mjøsa. In some places the lake was more than 400 metres deep and the total volume was almost like today's Vänern, the largest lake in Sweden and the third largest lake in all of Europe.

90-meter-high tidal wave

When the ice dam that held the lake in place at 665 metres above sea level suddenly burst, it was as if a plug was pulled out from a bathtub.

Colossal amounts of water destroyed the brittle sandstone where Jutulhogget is located.

The water flowed out of the lake and into the ice at the level of Rendalen. The water came out again under the glacier a little north of Elverum.

Further past Elverum, a 90- to 95-metre-high tidal wave full of mud and small icebergs cascaded down along the course of today's Glomma River.

The water found its way over Flisa, Kongsvinger and down Groruddalen in Oslo.

Metre-thick sediments in Romerike are remnants of the natural disaster.

Watch nature photographer Erik Jørgensen's YouTube drone video from Jutulhogget and its very special landscape:

New simulations

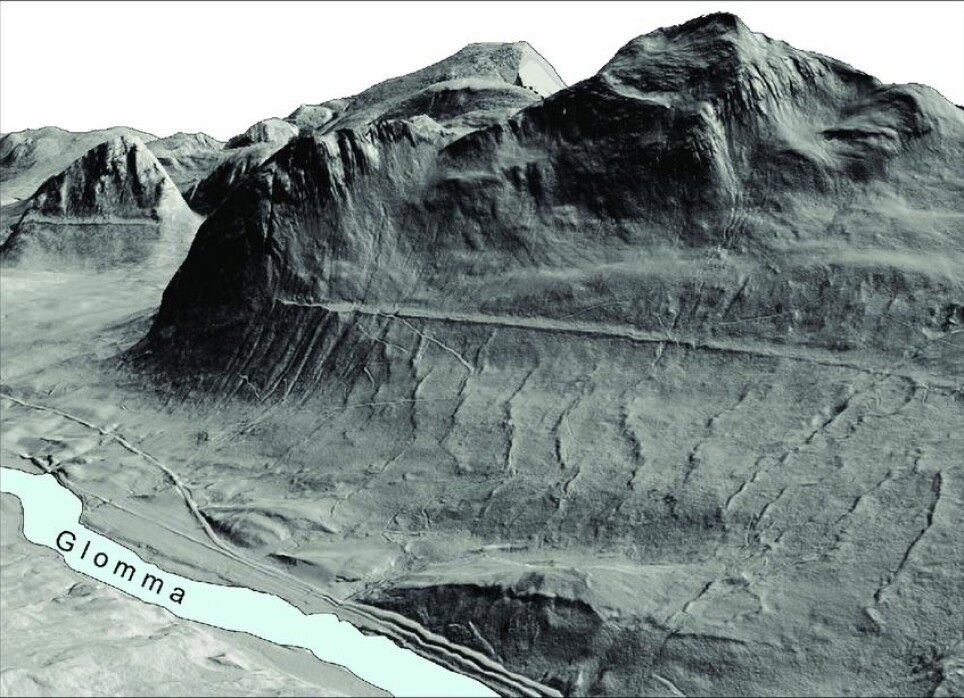

“The new mapping and new simulations we have done have greatly reduced the uncertainty about the size of the flood,” Høgaas says.

These simulations are based on the size of large flood-transported rocks and lines in the terrain, among other information.

The people back then

The first humans had come to Norway perhaps a thousand years before the megaflood washed over this area of Norway, called Østlandet. So what happened to them?

“It’s quite certain that human life must have been lost. It was unlikely that many were able to escape when this flood of water came down Østlandet,” he said.

“Those who survived were probably in a hurry to get high in the terrain,” Høgaas said. He is curious as to whether Stone Age archaeologists will be able to find traces of the people and the disaster they must have experienced.

A thick layer of fine-grained sand (silt) lay like a lid over the trapping and hunting areas of the Stone Age people.

“People who lived in Romerike and around the Oslo Fjord in the Early Stone Age probably had their livelihoods more or less destroyed,” he said.

Here you can see a YouTube video where Fredrik Høgaas presents his findings to members of the Geological Society of Norway (In English).

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

References and sources:

Fredrik Høgaas and Oddvar Longva: “The early Holocene ice-dammed lake Nedre Glomsjø in Mid-Norway: an open lake system succeeding an actively retreating ice sheet”, Norwegian Journal of Geology, 2019

Louise Hansen, G.A. Tassis, Fredrik Høgaas: “Sand dunes and valley fills from Preboreal glacial-lake outburst floods in south‐eastern Norway — beyond the aeolian paradigm”, Sedimentology, September 2019.

———