This was once solid rock when the small label was attached to the sample.

Now, it is reduced to mere gravel.

Devastation ravages at the museum in Oslo: 100-year-old rock samples crumble to dust

Crystals disintegrate. Labels turn to coal. Sulphuric acid seeps from solid rock. A plague is spreading through the collections at the Natural History Museum.

In the mineral collection at the Natural History Museum in Oslo, there are 44,000 stone specimens. Among them are pieces of ore from the 18th century, marked with ancient alchemical symbols that were the precursors to modern chemistry. Shimmering crystals from deep within the Earth.

There are also type specimens: the original stones used to define new mineral or rock types. These are the benchmark samples against which all others are compared.

You would think such collections would last forever. After all, they are made of stone.

But recently, something has been happening to the collections at the Natural History Museum in Oslo.

Each time Professor Henrik Friis opens a drawer, he faces uncertainty: Will the samples inside still look as they did the last time he checked?

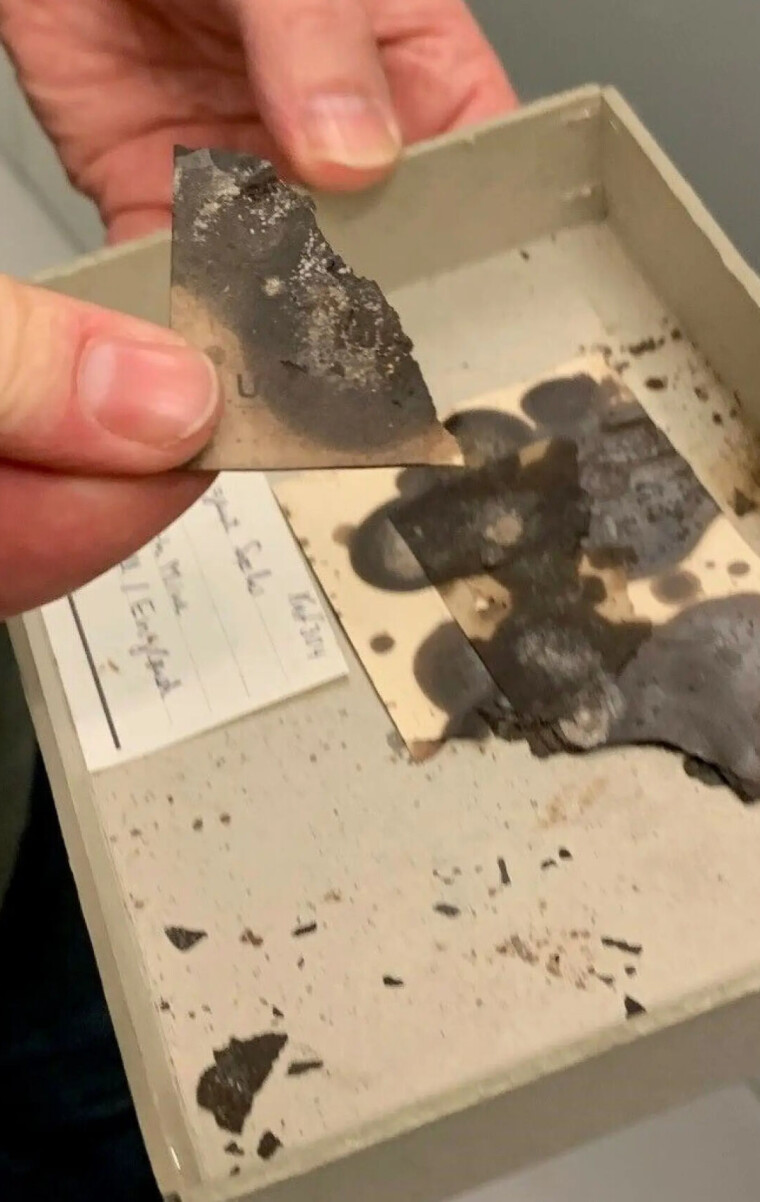

Sulphuric acid has seeped from the mineral sample stored in this box.

The acid has transformed its label into charcoal.

Chemical reactions within the pyrite of this mineral sample have caused the stone to emit sulphuric acid, which now sloshes at the bottom of the container.

"As I pull out a drawer, I notice – oh no – a sample has fallen apart," says Henrik Friis.

(Photos: Ingrid Spilde)

The sample might just have developed cracks or a dull coating over crystals that were once shiny.

But in some cases, the process has progressed so far that the original stone has completely disintegrated.

What on earth is happening?

Pyrite disease

"It's called pyrite disease," says Friis, who is responsible for the mineral collection at the Natural History Museum.

Pyrite is a very common mineral that occurs both on its own and mixed with many other types of rock. It is also known as fool's gold or iron pyrite.

The mineral is composed of iron sulphide – molecules consisting of one iron atom and two sulphur atoms – which form beautiful, gold-shimmering crystals.

However, when this substance is exposed to high humidity and oxygen, chemical reactions can begin to occur. Sulphate, or even sulphuric acid, is formed.

Both are bad news for the stone samples.

Explodes from the inside

Sulphate molecules are larger than pyrite molecules. When the transformation occurs, the sulphate starts to expand within the stone, causing cracks to form. These cracks allow even more moisture and oxygen to seep in.

"And then you have a process that's almost impossible to stop," says Friis.

The mineral essentially explodes from the inside out.

In some samples, sulphuric acid also forms – sometimes in significant amounts. Friis holds up a stone sample sealed in a plastic container, where sulphuric acid sloshes at the bottom.

When stones are stored in open boxes, the sulphuric acid can evaporate, damaging nearby rock samples, boxes, and labels. The labels are reduced to charcoal.

"Sulphuric acid pulls water molecules out of the paper, leaving behind only carbon," says Friis.

"This means that not only the stone is destroyed but also the cultural and historical documentation that accompanies the sample," he says.

Damages fossils

These chemical processes primarily affect pyrite samples. However, since pyrite is very common and often mixed with other minerals, pyrite disease can impact drawers throughout the entire mineral collection.

And even the fossil collections.

Many fossils are embedded in rock that contains pyrite. The mineral may also have penetrated the cavities in the bones. When pyrite disease strikes, the ancient fossils can break apart from the inside out.

In 1996, for example, a large section of the hip of the famous Triceratops Hatcher fell to the ground right in front of spectators at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. The fossil was found to have succumbed to pyrite disease after being on display since 1905.

Jørn Hurum's ichthyosaurs at the Natural History Museum have also been affected by the disease.

"Absolutely, many of the skeletons are impacted. This is a problem for all museums," Hurum tells sciencenorway.no.

Cabinet of death

When Friis finds a sick stone in the collection, he removes it. He has gathered a couple hundred samples that are breaking apart. The worst cases are stored in a separate cabinet – the cabinet of death. Here, boxes are filled with gravel and dust.

Strangely, this plague has not always been an issue in the mineral collection at the Natural History Museum.

By a stroke of luck, Friis has a reasonably clear idea of when the degradation of the stone samples began.

Intact in 2012

Typically, museum mineral samples are labelled in a special way. Each has a label on the box and a number attached directly to the stone. However, in the past, the samples at the Natural History Museum lacked numbers on the minerals themselves.

When Friis joined the museum in 2012, he initiated a project to add these labels.

This means there are exact records of when the samples were last seen without pyrite disease.

"Whoever labelled the sample wouldn't have placed a label on a pile of gravel," Friis points out.

This allowed him to track significant changes in the mineral samples over just a few years. These changes coincides with a major event in the collection's history:

Its move from the old premises at Tøyen to new facilities at Økern.

A sudden change

During renovations of the Geological Museum, both the researchers and the mineral collection were relocated to rented facilities.

The wooden drawers containing stone samples from Tøyen were placed on shelves in large steel racks at Økern.

Friis believes something changed after this move.

"We have samples that were perfectly fine for a hundred years in the old museum. Then just a few years later, they're ruined. It's frustrating," says Friis, who was himself surprised by how quickly the process unfolded.

Uncertain extent of damage

Out of the 44,000 mineral samples in storage, a few hundred damaged rocks may not seem like a large proportion.

However, Friis is concerned that important samples, such as type specimens, could be lost.

Another issue is that the museum does not know how many samples may already be damaged. Many of the countless drawers in the collection have not been opened in years.

"What I do know is that every time I find a damaged sample, I set it aside. And I can see that this has really accelerated in recent years," says Friis.

He suspects the problem may be even more widespread than feared.

"Pyrite is the mineral where the transformations are most visible, but several other minerals have also been damaged in recent years. Even though the processes aren't exactly the same as pyrite disease, the outcome is the same," he says.

Photo at the top of the article: Ingrid Spilde.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.