Growing Norwegian weeds on international space station

A Windows update on the space station created a crisis moment for a Norwegian experiment on cultivating plants in space. Forskning.no followed events from NTNU’s CIRiS control room.

“Should I use the normal Windows user name?” asks Kathleen Rubins as she looks at her laptop.

Everyone in the control room is watching her on a big screen in the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Space (CIRiS) at NTNU Social Research in Trondheim.

Rubins is far away – she’s actually on the edge of Earth's atmosphere. She is an astronaut on the International Space Station (ISS), and today she is helping out on a plant experiment that is being directed from Trondheim.

To get to the plants that are locked in a sophisticated cabinet, she has to open the cabinet door. She needs to use the laptop to open the door, but is having trouble logging on.

Questions are coming in over the radio, both from ISS and other control rooms around the world. Does anyone know how to login?

Mona Schiefloe quickly leafs through a sheaf of papers. She is a researcher at CIRiS and has been tasked with sitting at the controls during this critical part of the experiment. She doesn’t know of any password and passes this information on.

The electricity in the room rises a few notches as everyone tries to find a solution to this unexpected predicament.

Forskning.no was in the control room when the Norwegian researchers planned to conduct a critical part of the experiment.

Plants in outer space

The ceiling of the control room is covered with small stars organized in familiar constellations. The scientists who set up the room in 2006 made small holes in the ceiling panels, and installed lights above them.

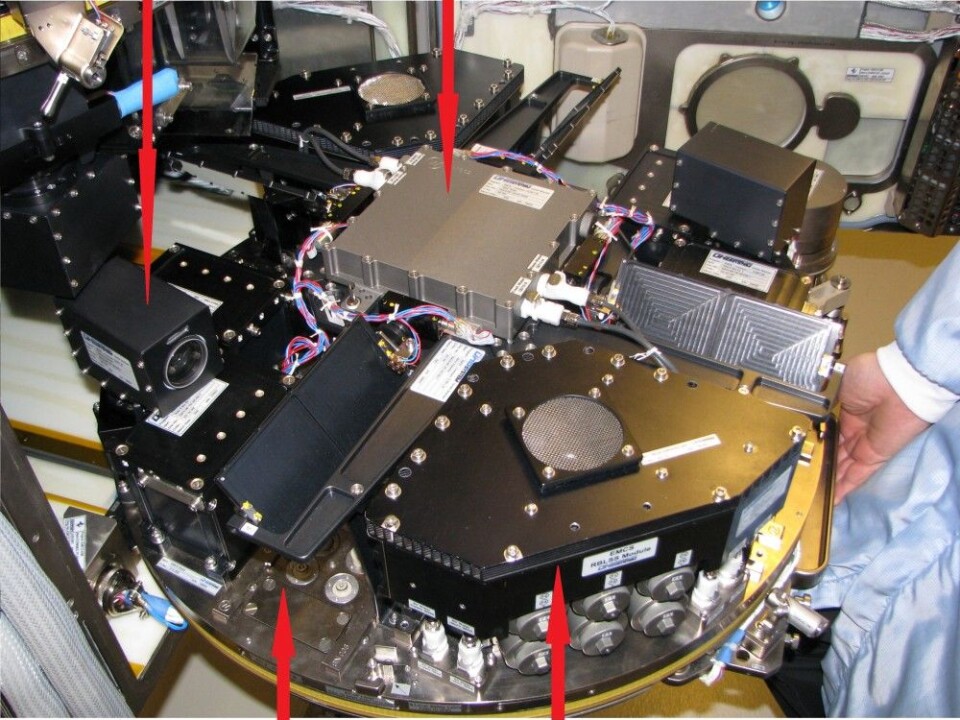

Under the ceiling are large screens and consoles that govern the European Modular Cultivation System (EMCS) module.

This is a system that makes it possible to grow small plants on the ISS, in part to see how plants react to the alien environment. The module is also used to develop techniques for growing plants on long space missions or on other planets, like Mars.

The EMCS module has two centrifuges that can spin the budding plants at different speeds and simulate different gravitational pulls, such as on Mars and on Earth.

In the video below you can see how a space centrifuge works:

Forskning.no visited CIRiS because of an experiment that made use of the EMCS module. On that particular day the experiment required the assistance of one of the ISS astronauts.

Astronauts have lots of tasks on the space station, and their time is valuable. Their days are packed with experiments and maintenance, as well as eating, exercise and sleeping.

“That’s why it’s important for things to work when astronauts help out,” says Carina Helle Berg, the project manager for the CIRiS control centre, called N-USOC.

Capturing a snapshot

Usually thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) is the plant of choice to cultivate on the EMCS module. This is a small weed that grows fast, and it is considered a model organism. This means that the plant's entire genome has been sequenced, and the plant can be used to understand fundamental processes in all plants.

The EMCS module and the control room in Trondheim have been in use since 2006 for several different research projects. Currently American researchers are using it to find out more about one of these basic processes, but the actual management of the experiment happens from Trondheim.

The idea is to find differences in gene expression of plants growing with almost no gravity, and then compare them with plants that grow under exactly the same conditions, only with simulated gravity.

One centrifuge in the module is quiet while the other spins at a speed corresponding to our Earth’s gravitational pull.

When forskning.no visits CIRiS, the thale cress has been sprouting for six days. The plants are about 1.5 cm tall and are ready to be taken out of their protected module.

The clock starts as soon the centrifuge stops spinning.

“Then the seedlings have to be frozen within 45 minutes,” says Helle Berg. “Researchers want to have a snapshot of what the plants look like having grown in these experimental conditions.

The second centrifuge has been at a standstill, so Rubins has a little more time to freeze those seedlings.

But before any of the seedlings can be frozen, she has to take the plants out of the centrifuge. This is when heart rates rise.

Windows update

The search for the password to stop the centrifuge from the PC on the ISS led nowhere. There is simply no one who has it.

“We have procedures for situations that arise when something doesn’t work, but it's always a bit stressful when it actually happens,” Schiefloe says.

And they do manage to fix the problem. Schiefloe is able to take direct control of the EMCS module from the control room in Trondheim, so she can access the centrifuge from the ground.

While the ISS staff is getting ready to open the door, the CIRiS team hears a voice from American ground control. They’ve found the cause of the problem:

It turns out that all the computers on the ISS were recently upgraded to Windows 7, and the password reset is an "unintended consequence" of the upgrade.

A satisfying click

And after half an hour with lots of phone calls and high pulse rates, everyone is ready to stop the centrifuge and open the door.

On the screen Rubins suddenly reacts and moves toward the door to open it.

The team in the control room gives a sigh of relief when it's obvious that she has managed to click it open, and Rubins turns towards the camera to give two thumbs up and a huge grin.

Once the door was successfully opened, the rest of the experiment went according to plan, with only minor delays. The cress seedlings were packed within the deadline and readied to be sent back to Earth.

The seedlings are part of a project being conducted by Imara Perera, a researcher at the University of North Carolina in the United States. She previously used the EMCS module to study molecular biology in plants, and now she is conducting another round of experiments.

Relieved

“I'm tired, but pleased,” says Schiefloe after her shift is over.

She’s been in front of the console for nine hours, including some intense ones while the password trouble and the rest of the experiment were going on.

“In retrospect it’s funny. Today I feel good since the issue was resolved,” she says.

Schiefloe says that little things almost always go wrong during an experiment, but she hasn’t been involved in any serious mistakes that have ruined a whole experiment.

“It went very well from our vantage point. I think Mona did an excellent job,” Helle Berg says.

She adds, “Ideally we’re able to carry out an entire activity without the astronauts needing any help, but it’s normal that we have to deal with some unexpected things along the way.”

--------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no