Vikings flaunted foreign bling

Viking women adorned themselves with what had been more everyday objects abroad. The women can be compared with today’s fashionistas.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Many women today might like to signal status and taste with exorbitantly priced imported handbags or watches. Over a thousand years ago our ancestors were doing the same thing – with different items.

Hanne Lovise Aannestad at the University of Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History is getting her doctorate on the subject of imported objects found in Viking graves in the 800s and early 900s.

In those days it was trendy here in the North to take ordinary objects from distant lands and convert them into jewellery and decorations.

“Look at this buckle, for instance,” says Aannestad, holding up a well-worn gold medallion from the 9th century excavated in Østfold County.

“It depicts two animals and on the reverse side are the remnants of two fasteners. I think it was once a mounting for a horse harness. One of the fasteners is nearly worn right off, and as I interpret it the other is a secondary fastener which was added when this was remade into jewellery.”

What once decorated a horse’s chest ended up gracing the breast of a Viking woman.

“I think this was an intentional transformation. People felt it was important to signal membership in a social class that had access to things from abroad. This gave them status,” says Aannestad.

New riches provided visible status symbols

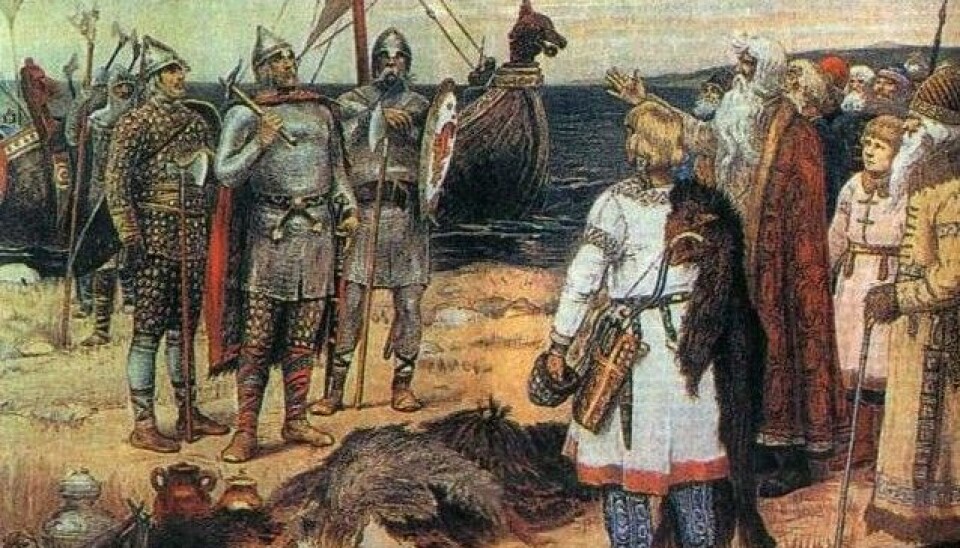

Viking raids escalated in the 800s. The spoils poured into Scandinavia from the British Isles, the Continent and from the Baltic region.

Participation in such voyages of trade and plunder gave status in a warrior society, which Norway was at the time.

Status objects, then as now, served little purpose if nobody could see them.

The jewellery that Aannestad has studied looks completely different than the traditional Norse trinkets, which are dominated by animal ornamentation and usually saucer shaped.

Flashing their riches

Several kinds of foreign objects have been found in Norwegian Viking graves. Some are intricate and costly, whereas others are more ordinary. The variety of items tell Aannestad about a society undergoing changes:

“We find exquisite things in the graves of the elite, but also foreign items in the graves of people from other social standing,” she says.

“I envisage this as a sign of an aspiring class, a class that flaunted their wealth if they had a chance to get hold of it.”

A Swedish archaeologist called the farmer-tradesman of the Viking Age braggart farmers. The old aristocracy had a traditional foundation for power linked to agriculture and land, but then came a class of nouveau riche people travelling around, trading and plundering. The researcher thinks Viking raids provided a basis for greater social mobility.

Christian objects on non-Christians

Aannestad studies objects from South-eastern Norway.

Many of these are Christian, probably taken from British monasteries raided by the Vikings. The large buckle Aannestad shows us was originally a Celtic cross which had probably been part of a larger altar decoration in a monastery or a church.

In the heathen North crosses and relics were probably not used in the same way as in England or Ireland.

“We find altar fittings, relic chests and holy books in heathen graves. I doubt that they were considered Christian objects. They were simply fine things that differed from the jewellery that people had previously,” says Aannestad.

Were women even more influential than presumed?

Aannestad has concentrated on jewellery in her analysis so far. So naturally she has studied women’s graves. Men were prone to be buried with foreign swords, spears, belt buckles and the like.

More men than women are buried with imported objects to accompany them into the afterlife. But so many women were consigned to their graves with foreign riches that Aannestad wonders if society was less traditional than assumed.

“A lot is unknown about the roles of women, particularly because the written sources we have are from the 1200s. By then we had already established traditions based on Christian ideology. The sources portray the women in the old sagas rather stereotypically – powerful and cunning noblewomen who urge their men into battle,” according to the archaeologist.

“I think that this material indicates that the roles of women were more wide-ranging. One reason is that there are many rich graves of females at the trading town of Kaupang.”

Aannestad says that weights and scales are rather common objects in women’s graves from this period. This means that they could have been directly involved in trade.

Aannestad plans to complete her PhD by the end of 2014.

---------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling