International PISA tests show how evidence-based policy can go wrong

OPINION: PISA gives scores to participating countries so they can be ranked from best to worst for the skills measured, as well as measuring how they stand globally over all skills. Too much importance is being given to these scores and rankings.

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) implemented by the OECD has been controversial since the publication of its first results in 2000.

Measuring the mathematics, science and reading skills of 15-year-old students every three years, PISA relies on broad international participation. In the 2015 test, as many as 72 countries joined the exercise, including those outside the OECD.

It’s common to find articles where PISA is presented as a measure of a country’s innovation and growth potential. But it’s also not rare to find others where the metrics used are contested as irrelevant and potentially counter-productive.

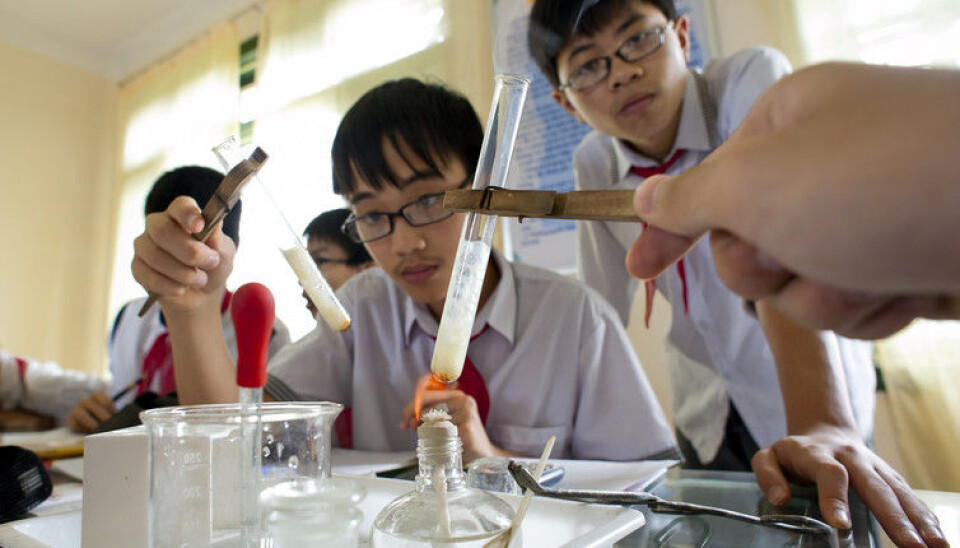

PISA results for 2015. OECD

For advocates of “evidence-based” or “informed” policy, PISA incarnates the dispassionate, objective facts that nourish the formulation of good approaches – in this case, in the field of education. It allows for country comparisons and can help identify good practices that are worth emulating.

Opponents of the program reject the choice made by the OECD to link education and economic growth. While this choice was explained at the beginning as a way of showing the high cost of a low educational performance, for some it also embodies a neoliberal framing of education policies, which forces the sector into the context of globalisation.

Post-normal science

In a new review study in the International Journal of Comparative Education and Development that I co-authored, we consider that facts such as those produced by PISA can be viewed through the lense of post-normal science. This approach is particularly apt for assessing scientific evidence when it feeds the policy process.

Post-normal science is a problem-solving strategy for issues where “facts are uncertain, values in dispute, stakes high and decisions urgent”. The concept was created in the 1990s by Silvio Funtowicz and Jerome R. Ravetz.

A key idea of the schema is “extended participation”, which suggests opening analyses to experts from different disciplines and forms of scholarship (one of the demands of PISA’s critics). It also points toward the active participation of relevant and legitimate stakeholders.

According to our review, a post-normal science reading of the PISA survey and its implications identifies a rich mix of methodological and ideological issues – in keeping with its tenet that the distinction between facts and values becomes problematic when the stakes are high.

PISA gives scores to participating countries so they can be ranked from best to worst for the skills measured, as well as measuring how they stand globally over all skills. Too much importance is being given to these scores and rankings, given the many non-transparent assumptions made by the OECD in their construction.

We don’t know, for example, how choices are made to include or exclude questions. There is also an issue about how many and which students participate in the test. The latter issue generates the so-called “non-response bias” and noticeably affects results.

Our review discusses the case of PISA non-response for England, where the bias turned out to be twice the size of the OECD declared standard error in 2003. This case illustrates how the results are much more uncertain and dependent on non-educational variables than it appears on a superficial reading.

In other words, the margin of error on the scores provided by the OECD is underestimated, and the ranking of countries from best to worst is more open to interpretation than one would understand from OECD analyses. To resolve this issue, the OECD should provide PISA users with a structured sensitivity analysis that takes all the variables in the ranking into account.

Ideally this analysis could be made by the users themselves, but this would only be possible if the OECD made all data available, which is not the case at present.

The worldview selected for the PISA analysis is also contentious. A main issue with PISA’s ambition to measure life skills needed to function in knowledge societies, for example, is that these skill are assumed to be the same across countries and cultures. Nor is it clear that all societies can safely be assumed to be destined to become “knowledge-oriented”.

Other fundamental questions emerged from our reading, too. Is it acceptable to see education as an input into growth? Does PISA “flatten” curricula – narrowing our collective imagination regarding what education is and ought to be about – and encourage focusing on a subset of educational topics at the expenses of others?

As noted by our study, country comparison is achieved by “ignoring the great diversity of curricula across the participating countries – diversity which might in fact be a source of country-specific creativity and well-being”.

Urgency and caution

The PISA controversy is a helpful reminder that citizens in democracies must be critical of the facts that feed into public discourse. This predates any alarm about the emergence of the purported post-truth society, though that has made these discussions are more urgent.

Facts must be taken with caution. For example, PISA scores have supported such inferences as this paragraph in a 2014 study prepared for the European Commission:

If every EU Member State achieved an improvement of 25 points in its PISA score (which is what for example Germany and Poland achieved over the last decade), the GDP of the whole EU would increase by between 4% and 6% by 2090; such an 6% increase would correspond to 35 trillion Euro.

The authoritative tone and use of crisp numbers here suggest causality – from education to growth – and an air of accuracy in a claim that is more like an act of faith than the result of scientific processes.Our review of the PISA controversy also highlighted a problem of power in the use of evidence. With PISA, the OECD – an international organisation composed of unelected officers and scholars – has constructed a neoliberal framing of education policy and used its authority to dominate the global conversation, potentially at the expense of national or regional authorities and institutions.

This “global super-ministry of education”, in the words of an educator quoted in our study, effectively marginalises alternative visions of education that would normally hold weight. Thus the idea of education as personal development and fulfilment, what Germans call Bildung, becomes invisible, because it cannot be used as an internationally comparable metric.

Different skills

A full discussion of all points of controversy would take more space than this contribution allows, and should touch on the tension in using metrics to appreciate cognitive skills, as well as the need for other skills, such as critical thinking, intrinsic motivation, resilience, self-management, resourcefulness, and relationship-building.

The OECD is unlikely to suspend or abolish the PISA study, in part because it serves a function. Before PISA, a country’s educational development was approximated by the average number of years of schooling there.

PISA raised awareness of other factors beyond classroom hours, such as literacy, that affect students’ educational outcomes. For those who study education, standardized tests like PISA also offer a useful instrument for comparing within and among countries.

Still, our study reinforces that democratic societies view “evidence-based policy” with a critical eye, querying who produced the evidence and whose interests are served by it. PISA is a strong example of the power asymmetries inherent in producing facts to inform policy.

In this case the OECD, possibly the most muscular player in the arena of international education policy, can frame evidence around its preferred norms and impose them on public discourse.

Andrea Saltelli, Adjunct Professor Centre for the Study of the Sciences and the Humanities, University of Bergen, University of Bergen

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.