People are more generous to each other at festivals

Much of the festival experience doesn't really happen during the concerts, but between people themselves, in the tents, a festival researcher says.

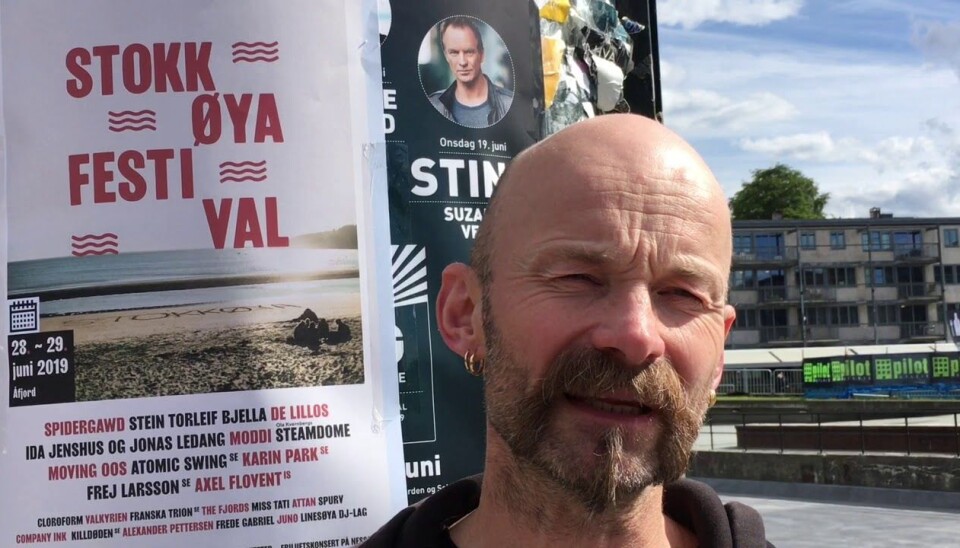

Aksel Tjora is a professor of sociology at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) who studies how people behave at festivals.

Festivals make people behave differently than they ordinarily might. Just look at what happened at Woodstock, the grandfather of all music festivals a half-century ago, where half-a-million people rolled around in the mud, danced naked in the rain and had a wild time.

Aksel Tjora has made festival life an active part of his research portfolio. He is a sociologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) who has worked with other sociologists to understand just what happens when we go to festivals.

One goal has been to figure out why people want to go to festivals in the first place.

The researchers have found that people don’t go to festivals just because of the music.

“Musicians who are dissatisfied with audience response should keep in mind that not all participants come just because of the individual artists,” Tjora says.

Using a lifeguard tower to watch the action

The researchers have built tall towers, like the ones lifeguards use, where they have sat and looked out over the sea of people.

“This arrangement was meant humorously, a little inspired by the movie Kitchen Stories,” says Tjora, where a researcher sits on a lifeguard tower and observes what’s happening in a single man’s kitchen.

They have also mingled with festivalgoers, but with signs on their chests identifying them as researchers studying the festival.

“It is ethically important that the participants were aware that they were being observed by researchers. But we were well received, and many joked that they would have to watch their behaviour since we were there,” he said.

More generous and outgoing

“People are more generous to each other at festivals, they’re more likely to chat with people they don’t know. Just being able to relax, be a little more socially inclusive than otherwise, is something attractive for people,” Tjora says.

For example, Norwegians, who tend to be somewhat socially reserved, get a little looser.

“They mingle more with people they know and don’t know, which is an unfamiliar situation for us Norwegians. And this affects us a lot,” he said.

This is where the sociology comes in, in that social situations affect us all the time, he explains.

Escape the everyday

The Øya festival in Oslo and Stereo in Trondheim are typical city festivals where people mostly attend the festival during the day or evening, but return to their homes after the festivities are over.

“In this situation, the festival defines a kind of zone where it’s OK to be slightly different. You can put on your blue shirt and put on shorts and t-shirts, and put the reality of your work or family aside, a little,” Tjora said.

It feels good to experience something completely different from everyday life, he says.

The team of sociologists has also studied tent festivals, of which the Roskilde Festival in Denmark is one of the best known in Scandinavia. These festivals are different in that the participants live on site for several days.

Pre-party festivities begin early

If asked, Tjora says he likes tent festivals better than city festivals, because tent participants create much of the festival atmosphere themselves.

“It’s the festival participants themselves who create the festival atmosphere,” Tjora says. “A lot of the festival doesn't really take place during the concerts, but between the tents.”

In particular, he thinks the transition from the early morning breakfast atmosphere to pre-party festivities is special. People open their first beer earlier in the day than they normally would otherwise.

“You open your first beer at twelve, or one or two o’clock. This is very un-Norwegian, and can feel almost on the verge of immorality. But it’s also a shared, social activity,” he said.

“When the first person opens a beer, the unwritten social rules say that everyone else should also open a beer,” he said.

Thus begin the pre-party festivities, where people define the transition collectively, and often begin very early in the day.

Needs social lubrication

In addition to mingling, festivals are characterized by beer and food.

The festival atmosphere is also about being able to have a glass of beer or wine in good company, he says. Drinking is an important part of festival culture.

“We see that people need social lubrication to mingle with friends and strangers without it feeling too awkward,” says Tjora.

A mix of culture and research

In June, Tjora’s own university sponsored the Big Challenge Science Festival in Trondheim, where researchers made presentations about their work in a more entertaining, accessible way.

“The festival combined science communication with cultural activities, with a mix of professional presentations and music in the evening,” Tjora said.

In Norway, at least, this is a new approach for a university to take towards public outreach about science, he said.

---------------------------------