Political news is hard to understand

Many viewers find news about politics a tough nut to crack. The professional pundits engaged by TV channels make it all the harder.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

This was revealed in a study made at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The results show a large portion of the political news presented on TV and in daily papers demands loads of political savvy from the public.

When readers and viewers don’t get the message in political news stories they switch channels or turn the page to entertainment, sports and the like.

It appears as if the way political journalism is being reported could be widening the public’s knowledge gap rather than bridging it.

The distance between those who are enlightened about political developments and those who remain in the dark has been mounting in recent years.

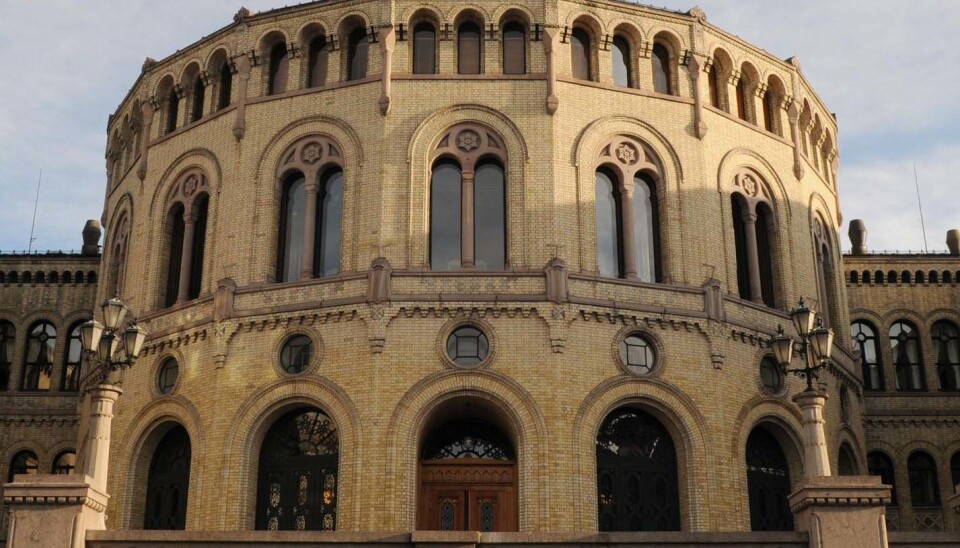

Storting Election 2009

Eva-Therese Grøttum at NTNU wanted to find out how hard it was for the general public to comprehend political journalism in Norway. So she studied the two daily newspapers VG and Dagbladet and the TV channels NRK and TV2 during the final five weeks prior to the parliamentary elections in 2009.

Grøttum carried out the study as part of her Master’s degree thesis.

In collaboration with Toril Aalberg, professor in media sociology at NTNU, she looked at the media’s use of experts as sources in their political news coverage.

Half of Norwegian voters are usually undecided about which party to vote for until the last weeks before an election. This makes coverage of politics all the more important during these periods.

Grøttum and Aalberg searched the four media for difficult concepts and metaphors that were not explained in news items. Then they used these breaches in the news presentations to gauge the degree of difficulty of the political news content.

The election study in 2009 showed 35 percent of the voters didn’t know the name of one of the main political leaders - Liv Signe Navarsete, nor that her Centre Party is one of the three parties in the current coalition government (the others are the Labour Party and the Socialist Left Party).

The researchers sought to find out whether news reports about Navarsete or the Centre Party mentioned this.

NRK is the hardest

When the researchers compared NRK, TV2, VG and Dagbladet, they found that NRK (The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation) had the most unexplained references and thus demanded the most of its public.

A total of 18 percent of NRK’s news stories required a lot of previous knowledge about politics and 46 percent required at least a modicum of political awareness.

About 50 percent of VG’s and TV2’s news stories could be comprehended without prior knowledge of the political subjects.

According to Aalberg a rather large share of the political news stories in the papers and on TV called for a considerable amount of previous knowledge.

You need to know who the politicians are, their positions in the political landscape, and you have to recognise political terminology and political metaphors,” she says. “Without that prior knowledge it’s hard to comprehend what the news is about.”

“This is no problem for people who are interested in politics,” says Aalberg.

She thinks a lot of political journalism is alienating for the many who aren’t particularly interested. It can even make this large share of the voters less interested in politics.

Aalberg is also aware of the dilemma facing journalists and the media.

It’s important for democracy to make the political news easily understandable. But this increases the risk of news being trivialised, which would drive away the more discerning readers and TV viewers.

Turning off politics

NRK still maintains a central role in Norwegian news reporting. But it is also the news channel that demands the most of any viewers who want to keep track of politics.

“These days political news is still readily accessible in Norway. For instance in the middle of the talent programme Norwegian Idol, they might run an ad for an upcoming political news story, to catch the attention of a wider audience.”

At the same time, the range of accessible media is increasing in Norway, which also makes it easier to avoid exposure to any more intellectually taxing subject matter.

“The days are over when the public ‘had to’ see the news if they wanted to watch TV,” says Aalberg.

In the USA this development has progressed much further. There you have to explicitly opt for political news if you want to keep up with politics.

The political game

Now many journalists are drawn between the duty of attending to their social and democratic role on the one hand and meeting commercial and profit-oriented concerns on the other.

Media often tackle this by making news more entertaining and creating media-hyped conflicts in their coverage of political issues.

Professor Toril Aalberg has previously conducted research pointing in the direction of this being an unwise move.

Political journalists’ increasing focus on politics as a game doesn’t coincide with the priorities of most voters. The voters are primarily interested in political issues.

The discussion of political ploys involving likely and unlikely government alternatives captivates none but the most politically aware voters.

Political pundits

Grøttum and Aalberg have also collaborated in an investigation of the use of political analysts or commentators.

Research conducted in Denmark indicates the use of such pundits in political news journalism has increased dramatically in past decades.

Research in the USA showed the use of such experts in news stories doubled the knowledge gap between the public with little and those with a lot of political savvy.

As is the case with political journalists, many expert analysts are primarily concerned about the game or machinations of politics, rather than the political issues themselves.

Researchers discovered that such expert sources were used in 23 percent of the political news stories prior to the parliamentary elections in 2009.

NRK and the newspaper Dagbladet used experts in 32 and 29 percent of their stories respectively, whereas as the newspaper VG and TV2 used these pundits in 18 and 15 percent of their stories respectively.

Data from the study shows a clear connection between the use of expert commentators and how hard it is to understand a news story.

“These analysts obviously utilise a vocabulary that makes many political stories harder to undertsand,” says Aalberg.

Academics are clearer

The media used two types of experts to comment political news – academics and their own pundits.

In the weeks prior to the 2009 elections, 75 percent of the experts used in the four media were researchers and academics, and 25 percent were the media-employed pundits and personalities – persons from the so-called “commentariat”.

“We found a striking difference between these two groups,” says Aalberg.

According to the study the media’s own political pundits made the news considerably more difficult to understand than the academics. By comparison, just 20 percent of the news stories that academics joined in on required a lot of former knowledge.

“It’s not the researchers and university people that use the most difficult terms and metaphors; it’s the media’s own commentators.”

Journalist’s gut feeling

Many choices and a lot of the priorities in the media are based on the gut feelings of the journalists. This applies to the choice of news issues and their slant.

Norwegian journalists are very prone to thinking they’re the right ones to decide what kind of information the public needs.

The two NTNU social scientists who made this study think there’s a good reason for asking whether Norwegian political journalists are overly prone to use themselves and their own knowledge as the point of departure when they choose the subject matter they report.

-----------------------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling