Practical math in primary schools

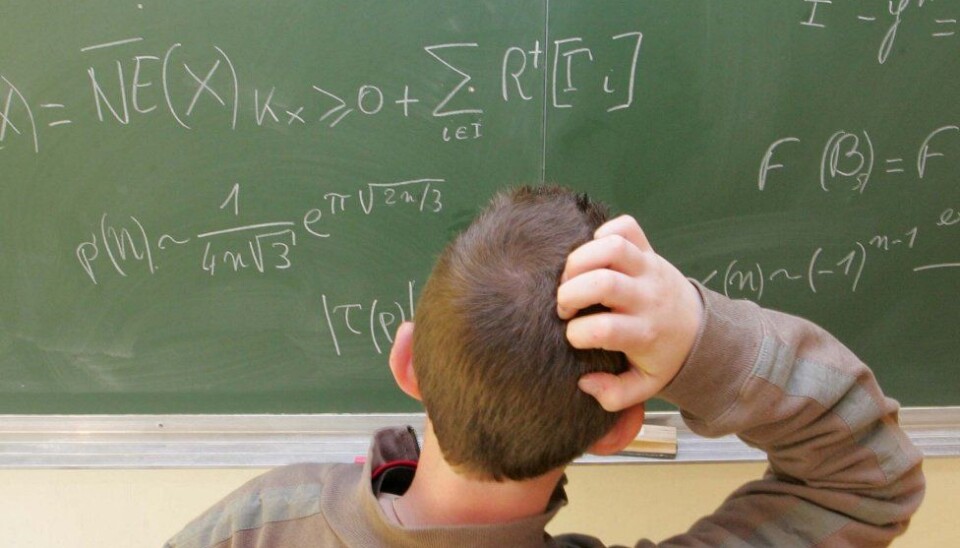

Experts disagree about the need for using practical activities to teach mathematics in Norwegian primary schools.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

After Norway scored quite poorly in the 2006 international Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) survey, politicians and voters started paying more interest in what was going on in Norwegian classrooms.

The country’s results improved some in the PISA 2009 survey. But teaching methods are still subject to political disputes, especially the relationship between theoretical and practical approaches.

Cooking, role playing in which pupils pretend to be in stores, embroidery and origami are among the practical activities used by Norwegian math teachers to engage school kids and ease them into an understanding of complicated math.

But there is no consensus regarding the methods that work best and how much they should be used.

Competence and freedom

According to Frode Olav Haara, associate professor at Sogn og Fjordane University College, Norwegian math teachers need more competence and should be given a longer tether – they need more independence.

“We need to give teachers the opportunity to take some well-considered choices based on their own competence,” says Haara.

His doctoral thesis investigated the reasoning that math teachers cite when using practical activities as an educational tool.

“If we raise their competence in the subjects they teach, educators become more independent and innovative. Then they can get a better pedagogic grip and steer their own work, rather than see it controlled by others,” says Haara.

Guilty conscience

Haara thinks that practical activities comprise a natural part of school math but teachers face a number of challenges when planning their teaching.

He explains that the three most common reasons for teachers cite for deciding whether or not to use practical activities in math lessons are professional and didactic knowledge, compromises that teachers feel obliged to make, and lastly, various practical dilemmas teachers encounter.

Haara adds that Norwegian teachers can suffer pangs of guilt when they use a practical approach.

“This is because on the one hand teachers are supposed to use more practical activities and are told to do so from every corner, but they also struggle to find good didactic tools. It’s a question of how well they master their discipline.

“If they do use these methods they run into problems squeezing everything into the standard curricular plan, covering all the math they are expected to teach, and this is a burden on them too.

Haara thinks the solution is to give teachers a better education and more freedom.

“I feel that teachers lack the elbow room they once enjoyed. Ideally you want competent teachers who are given the liberty to use a variety of methods.”

Research needed

But Hermundur Sigmundsson, professor at the Department of Psychology at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and head of a research group for education and development of skills, stresses that practical math activities need to be based on research.

He calls for a stronger focus on the prime goal of education – which boils down to giving pupils more knowledge.

“If international research shows that some methods are better than others, well, certainly we should use the better ones,” says Sigmundsson.

In an article that was published in the daily newspaper VG in 2009 he wrote that the countries ranking highest in math in the PISA survey were those that stressed proficiency and pure mathematics.

He also wrote that the PISA survey from 2003 reveals that Norwegian pupils who were given specific teaching in pure mathematics scored above average, whereas no studies indicate it better to base teaching on applied mathematics.

Teachers decide methods

Sigmundsson also says that major countries like France and the UK have taken recent years’ education research into consideration and re-focused on methods backed up by scientific findings.

“But what do Norwegian students at teachers’ colleges learn about the best approaches? Their curriculum ignores the issue, so how can they teach something that they haven’t been taught? Getting this right is enormously important,” he says.

In Norwegian national education plans, for instance regarding the subjects Norwegian and math, no guidelines are provided instructing teachers about preferred methods. Teachers are expected to make this decision themselves in accordance with the college training they’ve received.

Practice and repetition

Sigmundsson thinks teachers’ lack of knowledge about methods is compounded in Norwegian schools by insufficient individual follow-ups of pupils.

“Follow-ups are essential to making knowledge stick. Math also requires plenty of practice and much needs to be repeated to make it automatic.”

“Good math teachers manage to combine practical activities and a focus on what pupils need to learn. I feel that practical activities and game playing are often used without the teachers having any clear notion of what they expect the pupils to learn.”

Sigmundsson emphasizes that his intention is not to criticize teachers in Norway. His concern is that they haven’t been given the education they need.

“We have to get solid, research-based methods of teaching into the teachers’ colleges. We have to ensure that all teachers master them and can use them properly.”

Translated by: Glenn Ostling