Norway's mountain landscape has changed dramatically

It’s easy to think that the Norwegian mountains have remained unchanged for hundreds of years. New research reveals that people and animals have affected the landscape far more than you might have guessed.

Often, what we imagine a cultural landscape should look like reflects how it was some 50 years ago, when the adults of today visited the countryside with their parents and grandparents.

But a new collaborative research project on Dynamic Landscapes (DYLAN) involving biologists, palaeoecologists, archaeologists and historians shows a dramatically different picture of how Norway’s mountain landscape has evolved.

The Research Council of Norway has funded the multi-disciplinary project that takes a long-term perspective on how a landscape changes.

Many changes over time

“The cultural landscape that Norwegians travelling in the mountains encountered 50 or 100 years ago was in reality a new landscape,” says researcher Per Sjögren.

By the mid-1600s, Norway’s population had regained its pre-Black Death pandemic size. The population doubled by 1800 and again by 1850, with the result that during the 1700s and 1800s people used the mountain landscape far more intensively than previously.

This had dramatic consequences for the mountain scenery.

The pressure on land resources in the valleys of southern Norway mounted, and the mountains were used to increase food production.

In Northern Norway reindeer herding increased and became the normal way of life for many Sami. The larger herds of domesticated reindeer pushed out the wild reindeer.

Using interdisciplinary research methods, the researchers have enabled us to see the Norwegian mountains with new eyes.

Ecologically unsustainable use

Only now are we gaining an understanding of how much pressure these practices from the late 1700s until well into the 1900s put on mountain resources.

“At its worst point in the 1800s, this use was ecologically unsustainable,” says Sjögren.

Many people have a romantic view of summer farms in the mountains. But this image needs to become more nuanced. Farm life in the mountains was harsh. In many places, whole forests were cut down to provide wood for cheese making, and over time wood had to be transported over ever longer distances as the trees disappeared.

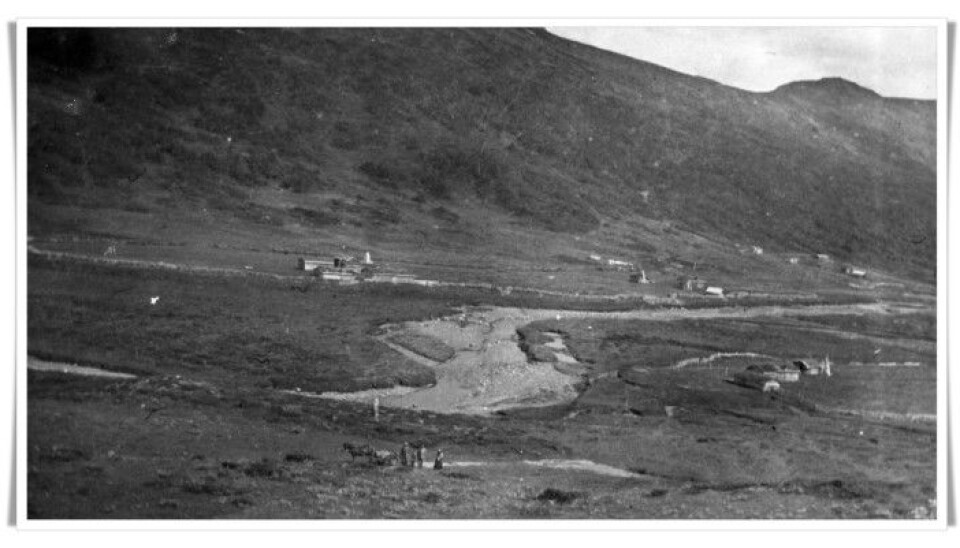

Cheese production on mountain farms took their toll on birch trees in the mountains.

This is the cultural landscape of the mountains that many Norwegians since World War II view as "real".

No “real” mountain scenery

The main message from the scientists behind this pioneering Norwegian research is that there is no one “real” landscape in the mountains.

Human activity brings constant change to the landscape.

Sjögren is a palaeoecologist. Much of his research involves examining pollen from the past. Because pollen is very well preserved in peat bogs, this research method offers great opportunities.

Pollen samples from peat can tell us what the landscape looked like all the way back to the Ice Age, making it possible to say with reasonable accuracy how many trees and plants grew at a given location in the past.

By combining this information with historical and archaeological knowledge about the same place, the multi-disciplinary approach reveals new understandings.

Sjögren and several research colleagues present much of this new knowledge in their book Fjellets kulturlandskap [The cultural mountain landscape].

Cultural and natural impacts

Sjögren’sanalysis of ancient pollen from peatlands in Norwegian mountains revealed, among other things:

- Something very dramatic must have happened with the vegetation in the mountains in the 6th century CE. Historians connected the event to the Norse mythological tale about a Fimbulwinter—three “mighty winters” with no intervening summers—that struck Norway several hundred years before the Viking era. Stories from farther south in Europe from the same time tell about the famine after a mysterious dust (from volcanic eruptions?) fell on the fields for several years.

- The Black Death came to Norway around the year 1350. Sjögren’s pollen samples clearly show plant and tree regrowth in mountain landscapes in the ensuing years. The pandemic halved the population and the additional food production was not needed. Much of the mountain landscape was abandoned until summer farming was revived again in the 1700s and 1800s.

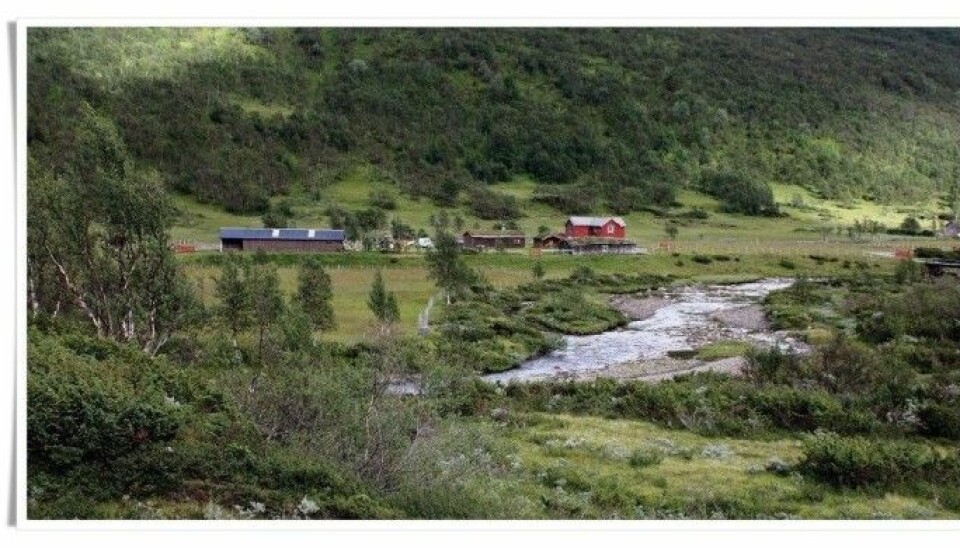

Today many cottage owners and hikers are seeing a dramatic vegetation resurgence in the mountains.

The mountains are no longer needed to feed the population in the same way as in past centuries. Better roads made it easier to collect milk from mountain farms, and from 1860 onwards the first dairies were built in the valley, obviating the need to cut timber for mountain cheese making. The use of synthetic fertilizers since World War II has increased food production in the lowlands, and Norway imports more food from abroad.

So now the mountain birch and other vegetation can be left in peace.

More sheep than ever before

Sheep and reindeer can slow the forest regeneration somewhat. But they feed on small plants and can’t keep up once saplings grow bigger, allowing woodlands to increase.

Vegetation is also climbing higher as the climate warms.

“Unlike in the past, today sheep and reindeer can freely graze on many of the best mountain pastures,” says Sjögren.

Historical data show that a good number of mountainous areas in Norway—especially Central Norway and Finnmark county—have seen increasing grazing pressure in the last 50 years.

Surprising research findings

The researchers behind this study have also found several parallel developments, which would probably surprise many people.

- The succession of mountain scenery is by and large a return to an earlier state.

- With the end of cheese making on the summer farms, the reduced logging of mountain forests has strongly contributed to the their regeneration.

- Less haying in the mountains has allowed more sheep to graze there. Domesticated reindeer have increased the grazing pressure in Norway’s far north.

Pristine nature is gone

forskning.no has repeatedly written about how new knowledge about Norwegian nature can help us understand the changes occurring in the natural world around us.

Researcher Anders Bryn at the Norwegian Forest and Landscape Institute (now part of NIBIO) points out how much of Norwegian nature is shaped by logging and livestock grazing. When people move out, the natural landscape takes over again.

“Many people think they’re in pristine nature, but really they’re in deforested landscapes,” he says.

Bryn also mentions that forest regeneration has its positive aspects, particularly the fact that increased woodlands provide more carbon sequestration.

On the other hand, as many as 60,000 Norwegian cabins may lose their view in the coming years.

According to a 2011 study by Yngve Rekdal, grazing sheep aren’t enough to control forest regeneration. He suggests humans may have to help the animals keep the landscape open in some places in the mountains through various means such as thinning the undergrowth.

————————————————————————

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no