Beware the bite of the warble fly

Reindeer aren't the only animals to suffer from attacks by the warble fly -- the insect will attack humans, too. The flies leave behind an unwelcome gift of eggs that mature under the skin and that in the worst cases can cause blindness.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

A small insect buzzes around the head of a child on a warm summer day. It makes a quick landing on the kid’s head and glues a cluster of eggs on a strand of hair.

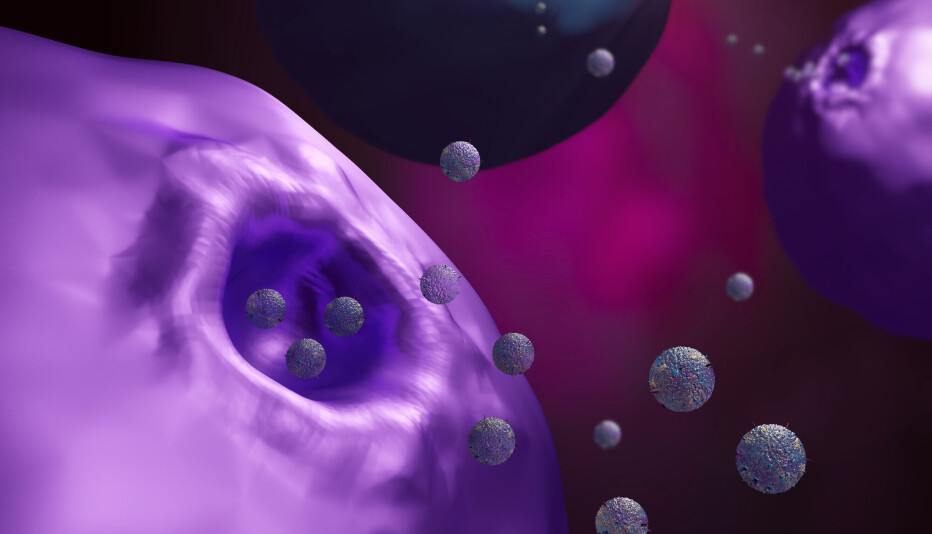

After a few days the eggs hatch. Microscopic larvae emerge and bore down under the scalp. In the weeks to come the larvae grow and wander around beneath the child’s skin. Bumps and swellings appear on the child’s face along with infections and discomfort. In the worst case, vision can be permanently impaired.

This may sound like a description of an exotic tropical disease, but it's an affliction found in northern Scandinavia, where an insect called the warble fly attacks not only reindeer, its preferred prey, but humans, too. Last year 17 cases of such parasitic infections were recorded among children and one adult in Norway’s northernmost county, Finnmark.

“A characteristic of the infection is that patients suffer swellings in the facial region, especially in the forehead and around the eyes. These bumps can last a few hours before disappearing and cropping up somewhere else,” says Chief Physician Kristian Fossen at the eye ward of the University Hospital of North Norway (UNN).

Not the first time

The reindeer parasite has given cause for extraordinary collaboration among scientists who study insects (entomologists), veterinarians, paediatricians and eye specialists (ophthalmologists). Each contributes with know-how from their special field in the war on the warble fly.

The outbreak in Finnmark last year was more extensive than it has been in previous years, but it wasn’t the first time the parasite had infected humans.

In a new report in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, researchers from Norway, Sweden, Italy and Spain describe seven cases in Scandinavia. All of these occurred prior to the latest outbreak in Finnmark.

Like a bumblebee

Professor Arne Claus Nilssen of Tromsø Museum grew interested in the yellow and black fly in the early 1980s.

The species, known formally as Hypoderma tarandi, is specialised in using reindeer as hosts.

“It is actually a nice looking insect. It looks a lot like a bumblebee,” says Nilssen.

Boils

The entomologist quickly adds that the larvae of the reindeer warble fly are far from attractive once they become parasites on other organisms.

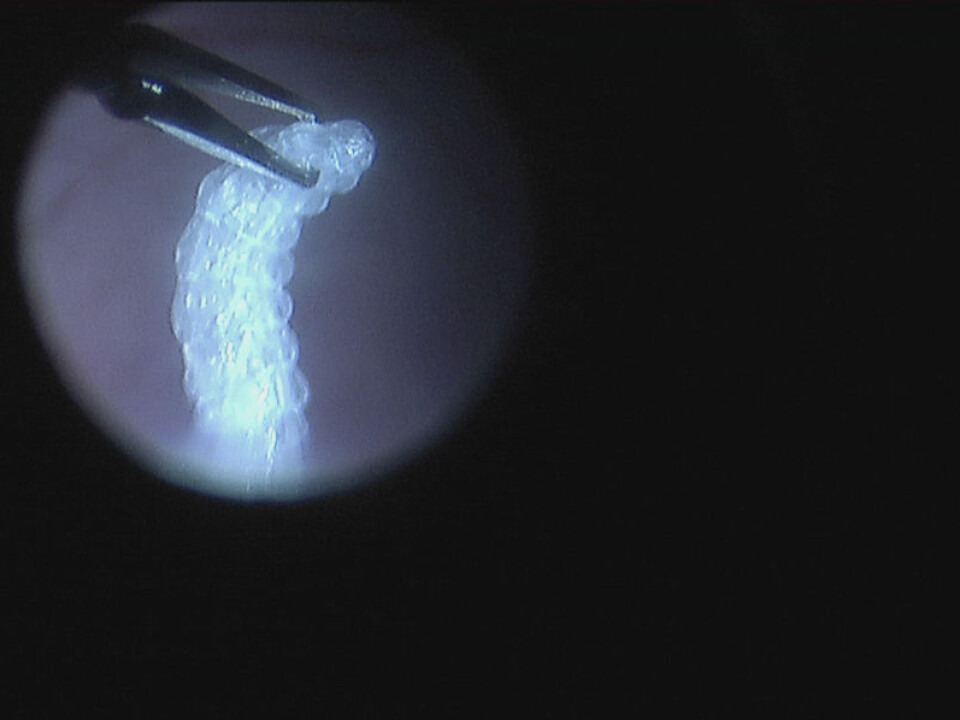

In their first stage, the larvae bore underneath the reindeer hide. They are then less than a millimetre long.

“In later stages they develop into large larvae which are visible as boils that erupt through the skin in late winter. Some reindeer have hundreds of these,” explains the professor.

In spring the larvae say thanks and goodbye and drops to the ground. Here they develop into pupae before emerging as adult flies and starting the whole cycle again by depositing a new cluster of eggs on the fur or hair of their victims.

Mistaken identity

When the warble fly swarms around reindeer on warm summer days, the animals try to shake them off or run away.

This type of warble fly has adapted to life as a reindeer parasite. When it lays its eggs on a human's head, the insect has actually miscalculated.

“They fly around searching for reindeer, but they make mistakes sometimes,” says Nilssen, who points out that we are not the ideal hosts for the flies.

The flies are unlikely to develop into adults with human beings as their nursery.

Blood samples

A blood test that indicates a parasitic infection by warble flies has been available for some time, because it’s a well-known problem in reindeer herds. The Norwegian School of Veterinary Science’s Section for Arctic Veterinary Medicine in Tromsø has now modified this test for use on human patients.

“The larvae excrete an enzyme which helps them move around beneath the skin. Hosts, whether reindeer or human beings, release an antibody against this enzyme,” says Associate Professor Kjetil Åsbakk of the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science.

The test detects the presence of this antibody, which means a blood sample can be used to quickly determine whether the patient has the parasites.

This test came in handy last autumn when doctors suspected they were seeing a spike in warble fly infections in Finnmark County.

Can attack the eyes

Once the correct diagnosis is made, the prospects for the patients are good. Patients are treated with anti-parasite medication that kills the larvae.

But if doctors are too late, the larvae can drill their way into the eyes, harming the patient's vision. UNN Chief Physician Kristian Fossen says the larvae have entered eyeballs in many cases.

The larvae seem to like the backside of eyeballs where the retina is found, and can cause serious infections.

Four years ago, Fossen surgically removed a warble fly larva from the eye of a patient. The operation was a success and the patient now sees well with the eye. Nilssen took the living larva with him back to the Tromsø Museum.

Unusual outbreak

Sixteen children and one adult were infected by warble flies in Finnmark last year. Hospital doctors Andreas Skogen and Jørgen Landehag in Hammerfest say that all these patients are doing fine.

No previous record has been made of an equivalent outbreak over such a short period. Perhaps this is simply because physicians have improved in making the correct diagnosis.

“We think there have been cases earlier that weren’t diagnosed,” says Andreas Skogen.

Perhaps people swell up with warble fly bumps every summer, but without serious complications and the parasites die without being treated.

Important diagnosis

Some of the individuals who were infected last year were initially treated with allergy medications and antibiotics until doctors discovered the real cause of the problem.

“Right now we don’t know why children are most prone to infection,” says Landehag.

It might be because they have thinner skin, or that because they are shorter, their heads are closer to the ground. Or perhaps it has something to do with their young immune systems.

There are plenty of unanswered questions, and researchers say they will continue to study the outbreak last year in future research.

Altered understanding

Immunologist and researcher Boris Kan of the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm has led the recent studies that have been published in the Nordic countries.

Previously, researchers have paid the most attention to the more critical cases, where patients have risked blindness. Less serious cases might have escaped diagnosis.

The cases that Kan studied in Sweden and the latest rash of cases treated at the hospital in Hammerfest have brought the parasite in focus.

“It seems to be a much more common problem than we thought. Probably just a small share of the cases involve the eyes,” says Kan.

——————————-

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling