What children seeking asylum want adults to know

Single minor refugees and asylum seekers want adults to see things from their perspective.

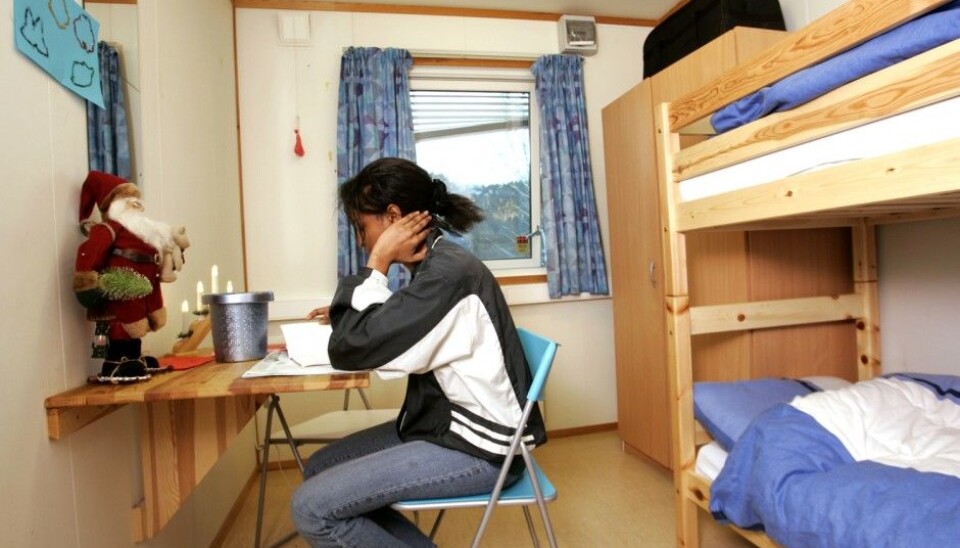

They’re often on their own for the first time, frightened, barely teenagers. Single unaccompanied minor refugees and asylum seekers who have come to Norway are vulnerable and in need.

Two psychologists decided to ask a subset of these children who arrived in Norway before the age of 15 what kind of advice they would give caregivers from Norway’s Child Welfare Service. The answers from 66 children, now living in municipal group housing, foster families or in reception centres, fit into four broad categories, the researchers found.

These were:

- Be nice

- Try to take my perspective

- Help me

- Give meaning to the rules

“Ask us”

The children had been in Norway for between one and four years when the psychologists asked them a simple question: "Do you have any advice for adults who work with children who come to Norway like you did?"

"Be nice," was one piece of advice. Indeed, several children told the psychologists about positive experiences they had with adults who had taken care of them.

But adults can also be strict, the children said. One boy said he had been bullied by adults. He was annoyed when one worker said he was a "child", as though the caregiver did not believe he had given his correct age.

Caregivers must not allow doubt about the children's stories to get in the way of their relationship with the child, the two psychologists wrote in an article about their study in the journal Norges Barnevern.

Expressing doubts about the children’s stories can weaken the child’s confidence in adults, the researchers wrote.

The children were concerned that adults try to understand them and see things from their point of view.

"It would be nice if they would ask what we need, for example," said a 14-year-old boy.

This is in keeping with a Swedish summary that concluded that employees at institutions where children are cared for must understand the children's situation. It’s not enough to understand psychology and have language skills; these workers must also have empathy, curiosity and respect.

Knowing and caring

One 15-year old boy said his guardian was very important to him, because he did not see him as a refugee.

"He does not think I'm an Afghan boy,” he said. “He thinks I'm his boy."

Some of the children thought that adults should pretend to be their parents, while others said that guardians and caregivers cannot replace the family they left behind.

And adults must not look at their work as just a job. They must be genuinely interested in getting to know the youngsters.

Heidi Linnerud at the Gjøvik Care Centre for single minor asylum seekers recognizes the truth what the children in the study say.

"The children are very quick to identify who really cares,” Linnerud said.

The Gjøvik center is currently home to 27 children, mainly boys from Afghanistan and Syria.

"Most employees really care about the children,” she said. “But we do also have people who work here because it's a job.”

Different needs

The children have very different needs, the psychologists explained. They feel that the advice given by the children is consistent with what is known about how professional caregivers should work with single minor refugees and asylum seekers.

Security, relationships and help with controlling emotions are some of the most important things that employees can give children who have been exposed to traumatic experiences.

Caregivers need to balance between caring for the child and using their professional skills. This is not a personal relationship where gut feelings should be allowed to drive decision making.

The job is complex— employees must find a way to see what each child needs. This can be challenging because the children are often silent when they arrive. They provide little information about themselves. The children and adults do not speak the same language, and there can be many different adults who work with the children.

A different study also showed that caregivers often do not listen to children seeking asylum, because they get swallowed up by paperwork.

Need to understand their situation

The youngsters in the study came from eleven different countries, most of them from Afghanistan. Some also came from Eritrea, Somalia and Sri Lanka. The vast majority were boys who were between 13 and 20 years old when they were interviewed in 2012-13.

Many bear the emotional wounds from war and turmoil and their long and difficult escape.

Another article based on the same interviews showed that the children have been affected in several ways. Many have experienced violence in the family.

The first survey of living conditions of children in Norwegian asylum reception centres who came to Norway 2015 showed that far more asylum children have high stress levels than among most children. More than half of the children were on the border of or were in a critical zone when it comes to emotional problems, according to the researchers.

In other words, caregivers have a lot to handle. They must help the youngsters talk about and address their difficult feelings. Several of the children interviewed asked for exactly this kind of help.

The caregivers “must understand how (the children) feel when they are sad and angry," says one boy, who continues to think of the father who hit him.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no