Immigrants wait longer to marry

Pakistani Norwegians marry later than they used to.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

How common is marriage among young people with immigrant backgrounds in Norway? How customary is it for immigrants and their children to find spouses back in their family’s home country?

Debates about the pros can cons of immigration in Denmark have often revolved around such questions.

Such controversies were magnified by the 24-year minimum age limit that was imposed by the government under Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen in 2002. The regulation demands that both husbands and wives are at least 24 years old before a spouse can be brought into the Denmark and granted legal residence.

The two non-socialist Norwegian parties the Conservatives and the Progress Party, which have been in power together for a year, are arguing for similar legislation. So too are their parliamentary backers, the Christian Democrats. The proposal is now being reviewed in hearings.

Norwegian and Danish social researchers have analysed the marriage patterns in the two Scandinavian countries to appraise demographic developments as regards the age of spouses brought into the respective countries. The found out the following:

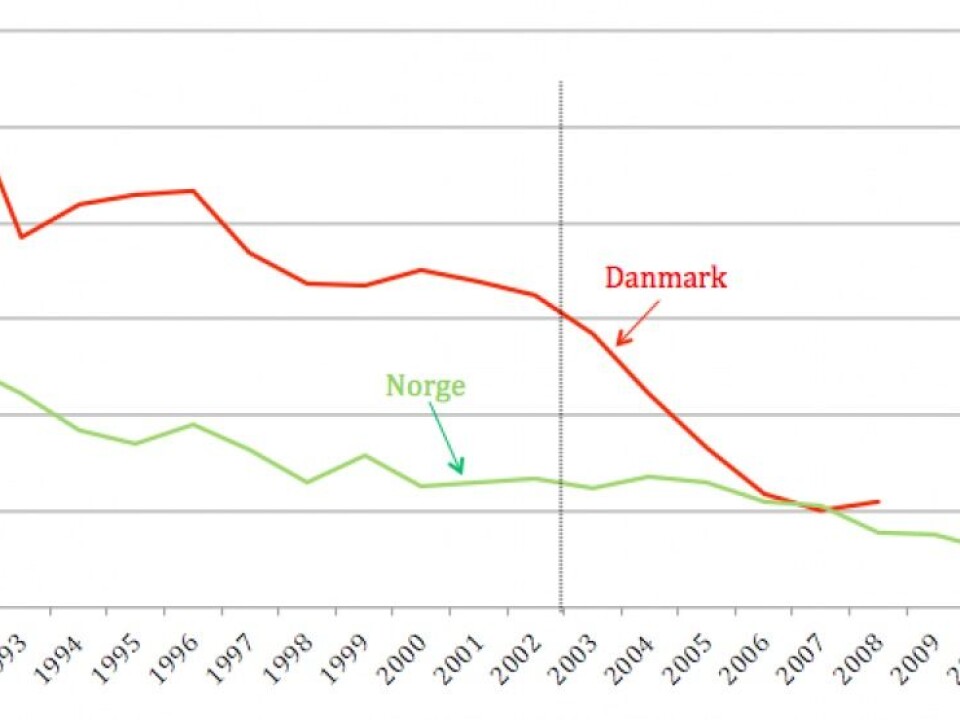

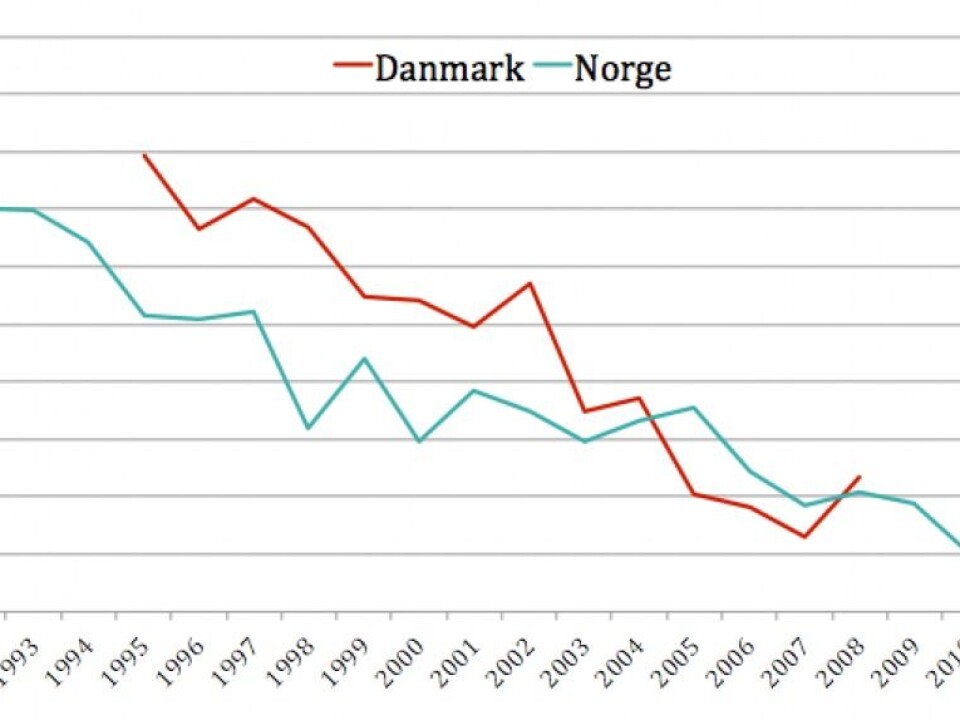

- Residents of Denmark with immigration backgrounds are now much older when they get married. But the same trend has occurred across the Skagerrak in Norway – even though Denmark’s neighbour to the immediate north has not had a similar law against importing young brides or grooms.

- Generally among non-Western immigrants and second-generation immigrants in both Norway and Denmark, spouses tend to be found in – or have roots in – the family’s original homeland.

Pakistanis and Turks

Pakistanis have comprised a fairly large share of the minority population in Norway for some time. In Denmark Turks have had a similar role. In addition, there are many Pakistanis in Denmark and many Turks in Norway.

Researchers have looked closer at these two ethnic groups.

Several objectives were behind the age 24 rule in Denmark. Anders Fogh Rasmussen’s non-socialist government wanted to use it primarily to hinder forced marriages. The current Norwegian government intends the same. Another justification was that when requiring a higher minimum age limit for such marriages to a person living abroad, more young persons with immigrant backgrounds would have a chance to obtain a higher education. Thus, they could become more easily integrated into mainstream Danish society. Although it was not overtly stated by the Danish government, it can be argued that another hope was that a reduction of imported husbands and wives from Turkey and Pakistan would also contribute toward a reduction of total immigration to Denmark.

The minimum age for marriage in Denmark and Norway, otherwise, is 18 years.

Surprising finds

“The tendency to get married at a young age dropped considerably in Denmark after 2002,” says Axel West Pedersen.

He and his colleague Anja Bredal at the Norwegian Institute for Social Research in Oslo have now collaborated with the Danish National Centre for Social Research in Copenhagen and conducted tandem studies in both countries. This allowed them to accurately compare statistics and trends.

“Our surprising discovery is that exactly the same thing has happened in Norway, without the age 24 rule.”

The researchers looked at these developments in the period 2002 to 2010. They have tallied such marriage practices among all non-Western immigrants, with a special focus on Pakistani and Turkish families in the two Scandinavian countries.

Higher marrying age

“The plunge in the share of second-generation immigrants who married young was much steeper in Denmark. But after a while we see the same thing happening among the descendants of immigrants in Norway.”

West Pedersen thinks the more dramatic decrease in Denmark can be attributed to the fact that until the 24-year age limit was passed, Turks in Denmark tended to get married very early.

“But when we compare Pakistanis in Norway with Pakistanis in Denmark, we see a nearly parallel trend. The rise in marriage ages is nearly identical in both countries,” says West Pedersen.

“The politicians behind the law in Denmark are probably right in saying that it has had an effect. At least it has had an impact on the Turkish minority in Denmark.”

“As for the Pakistani minorities in both countries, we observe an almost identical development. In Norway too there are increasingly fewer marriages between young people among the second generation Pakistanis, even though no such 24-year minimum limit has been enacted here.”

Education behind it all

“We think education explains the numbers,” says West Pedersen.

It is common among minority groups in Norway – among the immigrant parents and their descendants – to be ambitious with regard to social mobility.

Weddings are put on ice a few years so that young people can study and establish careers.

“We also see that a higher education has become a criterion for many of the young people and their parents when they look for partners. This applies to arranged as well as self-initiated marriages.”

Sociologists see a close correlation between choice of educations and the starting of families. But which is the chicken and which is the egg, so to speak?

“Danish politicians thought they could get immigrants to take higher educations by forcing them to delay marriages and postpone having children. But both the Danish and the Norwegian figures indicate that the process primarily flowed in the opposite direction. In other words, a desire for an education led to a decision to delay marriage and having children.”

“If the desire for a higher education is sufficiently strong the changes in marital age come about by themselves,” says the sociologist.

Married 21-year-olds

Fresh demographic figures show that hardly any 21-year-old Pakistani-Norwegian males are married. The corresponding share of married females at age 21 with Pakistani ties in Norway is 5 percent.

That said, the researchers are not convinced that all aspects of this trend toward a higher age for marriage among Pakistani-Norwegians are positive.

“Pakistani women in particular are starting to become better educated. Degrees in law and medicine are desired career paths among them. But this could mean that a rising number of them have trouble finding a partner in life,” comments West Pedersen.

Now about a third of Pakistani-Norwegian women are single at age 30. And the ranks of these unmarried women are growing.

No increase of marriages with ethnic Norwegians

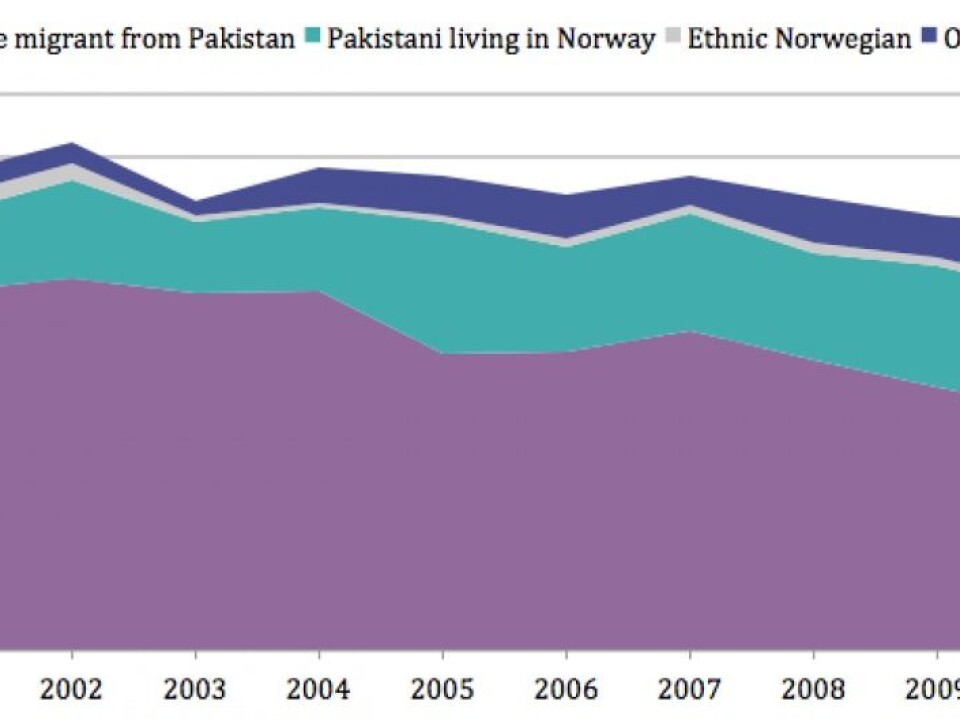

Ethnic Pakistanis hardly ever wed ethnic Norwegians. This has been the story ever since the first Pakistani immigrants arrived in the 1960s and 1970s.

“It has become a little less common for Pakistani-Norwegians to find spouses in Pakistan.

“But counter-balancing that, more second-generation Pakistanis in Norway are getting married to other Norwegian-Pakistanis,” explains West Pedersen.

Family immigration, in other words, persons granted residence on the basis of family relations to someone in Norway, accounted for 40 percent of the non-Nordic immigration to Norway from 1990 to 2012. During this period, six out of ten family immigrants came to re-unite with family in Norway. Four out of ten came to Norway to establish a new family.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling