Thrifty medieval bailiffs accidentally saved Old Norse texts

Norwegian archivists have found hidden treasures in medieval accounting records, including a slightly different version of the saga of Olav the Holy. Now you can see them online.

Medieval bailiffs in Norway were apparently very frugal: when it came to reinforcing the binding of their accounting records, they reused old manuscripts.

This may not be so surprising if you consider the nature of parchment itself: it was made from animal skins, most often from calves or sheep. If you needed a big sheet of parchment, you would have to slaughter one whole sheep for each page. That naturally meant access to parchment was limited during the 1500s and 1600s.

Around 1850, when the historian P.A. Munch learned from the then-Director General for Cultural Heritage that there were quite a few pieces of old manuscripts written on parchment that had been "hidden" in accounting records from the 16th and 17th centuries, he was elated.

The manuscripts were in Latin and Old Norse, but it was the Old Norse that was of most interest to Munch, especially pieces from the saga manuscripts.

Munch was familiar with a number of preserved saga manuscripts, but he believed that all the bits and pieces discovered in the accounting records meant that a great number of sagas were still circulating in Norway in the 1600s.

And that saga literature about old Vikings was still popular.

Tor Weidling from the National Archives of Norway in Oslo has worked with the roughly 550 pieces of Old Norse manuscripts that were eventually collected.

They have now been posted online at digitalarkivet.no.

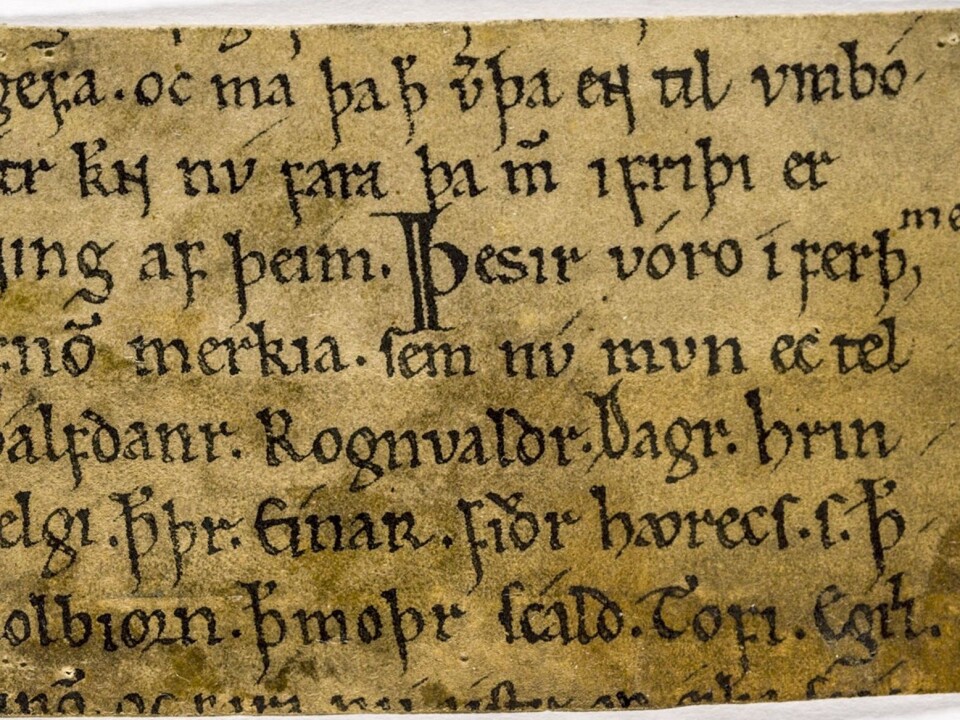

One example of interest is a portion of a manuscript on parchment that tells the story of Olav the Holy. This manuscript is from the last part of the 1100s.

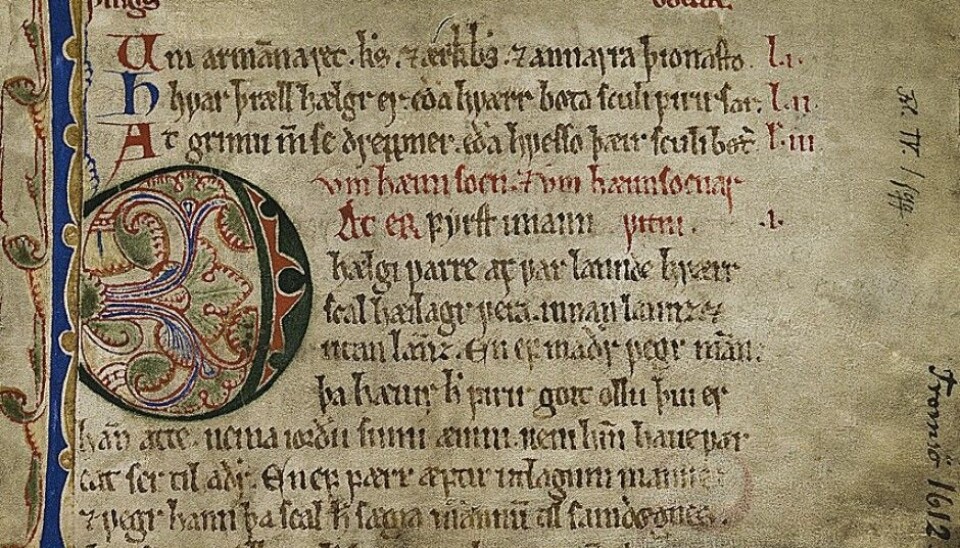

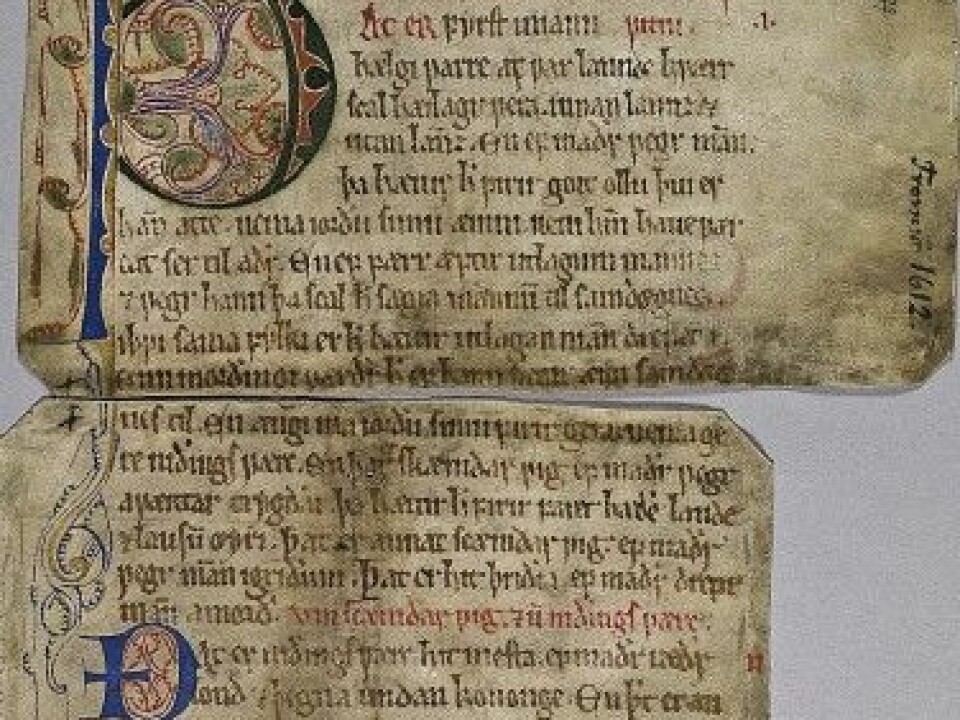

Another example is a fragment from the Frostating Law, probably written around 1300. According to one translation, the following sentence graces a beautiful ornate piece of parchment that forms the beginning of the Mannhelgsbolken, which is a paragraph in the law.

The first in the Mannhelgsbolken is that our countrymen should be peace-loving at home and abroad.

The Mannhelgsbolken has regulations on homicides, murder, violence, fighting and defamation. The sentence from the paragraph stating that every countryman should be peaceful means that he should not be insulted without someone being punished for it.

A large, decorated letter marks the beginning of the Mannhelgebolken.

Popular reading in the 17th century?

Weidling believes P. A. Munch may be correct, in that saga literature was popular in the 17th century — at least if Munch thought that educated people read it. This could have included priests with a Norwegian background, nobles still in Norway, and laymen, such as the top judges in the country and the most successful farmers.

"There may have been many Old Norse manuscripts, but that doesn’t mean there was one in every home. But it is not unlikely that in a large number of Norwegian settlements, someone had a manuscript,” says Weidling.

Reinforcements for accounting records

The manuscripts began to disappear little by little, but they also reappeared —cut and reused — as reinforcements on the spines of bailiffs’ accounting records from Norwegian administrative areas called len.

Weidling says this use of old manuscripts to reinforce the spines of books happened across the country. And bailiffs could generate many accounting books every year. For example, Akershus len, which was the largest in Norway, sent roughly 50 accounting books in 1624 to the Exchequer in Copenhagen.

But the question has to be asked: How could the bailiffs, even with their cynical reputation, be blind to the value of the old manuscripts they broke up and sent in small pieces with their books to the King of Denmark? Might they have thought about saving them?

"Some probably didn’t care much about them,” Weidling said. “And maybe not everyone knew what they had in their hands.”

Two other factors also likely played a role in the treatment of the rare manuscripts, Weidling said. One was that the Norwegian language itself had changed over the centuries.

“What was understandable in the 15th and 16th centuries might not have been comprehensible in the 17th century,” he said.

In addition, Danes and Germans began to play more of a role in the administration of Norwegian local affairs.

"They were perhaps not as interested in what was considered historically important to Norway,” Weidling said.''

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no