Knitting advice side by side with the Russian Revolution

How did Norwegian women get their news a century ago? It turns out that women’s weekly magazines offered up knitting patterns along with lots of international news, including the Russian Revolution.

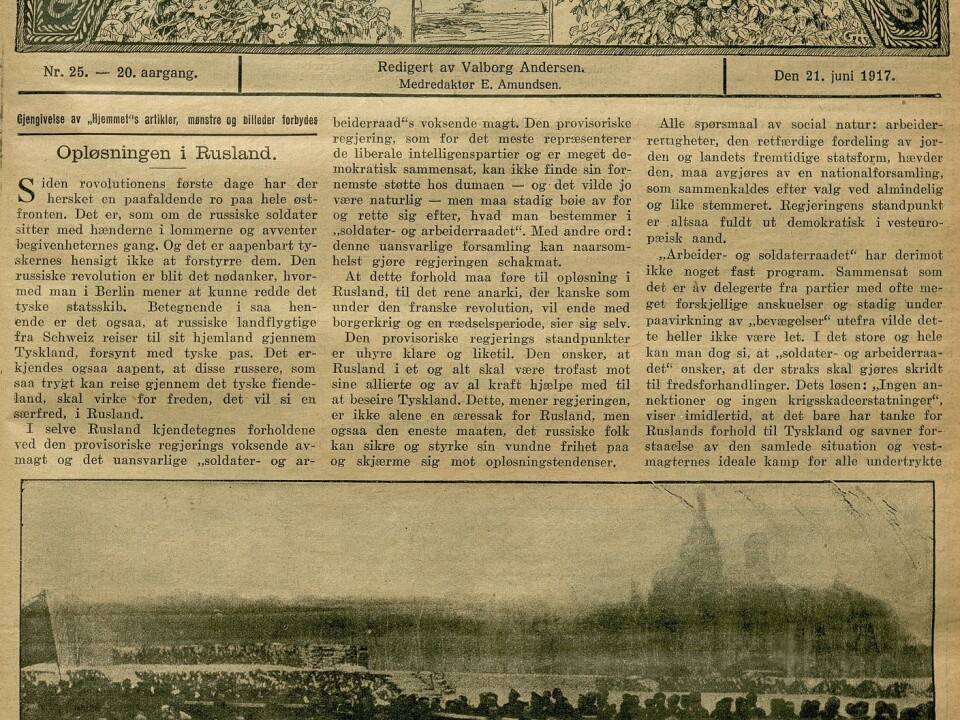

Canning advice, the latest fashion trends from Paris and… the Russian Revolution? An unlikely combo, from our 21st century perspective. But media researcher Birgitte Kjos Fonn says that women’s weeklies from 100 years ago offered their readers a varied window on the world.

“These weeklies had a surprisingly large amount of international news,” said Fonn, who is an associate professor of journalism at Oslo and Akershus University College.

Fonn has examined the content from two Norwegian weeklies, Hjemmet (“The Home”) and Allers Family Journal, from a century ago.

She is the editor of Media History magazine, which will publish a special edition this autumn on the centenary of the Russian Revolution. Her research, described here, has not yet been peer-reviewed by other researchers.

Angry at the Tsar

It was not just newspapers that were keen to tell people about what had happened during the First World War. Weeklies contained far more news than they do today.

Both Allers and Hjemmet had separate columns devoted to news from the war.

The monarchy was also strong material for the weeklies, just as it is today. But a hundred years ago, this was more than just news about fashion and gossip about the love life of the royals.

Many of the monarchies in question had real power. When the Tsar fell in the February Revolution, the weeklies began to write about the Russian Revolution.

Fonn expected to find a lot of politics in these magazines, because she had already discovered a great deal of political coverage when she read the publications from 1913, the year women won the vote in Norway.

But she was surprised to find that the weeklies were highly critical of the last tsar, Nicholas II, in 1917.

“Weeklies were generally believers in the monarchy. But here they did not mince words,” she said.

News of the royals and war

The weeklies expressed respect for the revolutionaries and disgust for the Tsar's brutal repression.

Nicholas II was deeply criticized. The writers seemed greatly shaken by the Tsar's treatment of the Russian people. The only way he had been able to rule was by "persecuting his people," Hjemmet wrote.

“It’s interesting that the magazines took such a clear stance on something that could be so controversial,” Fonn said.

“I think it also says something about the atmosphere in the Norwegian population, that people recognized misrule,” she said. “The weeklies can’t have been the first to challenge conventional wisdom. They were normally conformist, so it must have been a legitimate thing to say.”

There are several possible explanations as to why the weeklies would have supported the revolution.

Firstly, there was strong opposition to Germany during World War I, and recognition that the German war effort took its toll on the Russian people.

Moreover, there was a great deal of enthusiasm for freedom in the Norwegian population after Norway’s own independence in 1905, Fonn said. The weeklies expressed the opinion that tsarist rule had no place in a modern free state. They often used the word democracy.

Believed in the revolution

Allers opined that the Russian Revolution would lead to a pervasive democratization in Russia and liberation worldwide.

Hjemmet focused on the fact that there was no freedom of expression under the Tsar and that he had sent dissidents to Siberia.

This was somewhat ironic, Fonn observed, since the Communists came to be known for their brutal repression of opponents.

And even after the Communist October Revolution, Allers still wrote about the situation in a positive way. As late as December, the weekly wrote about the Russian Bolshevik government’s “untiring campaign for peace” and its “efforts for the Russian people."

“The weeklies were perhaps naive. But it's hard to know how much they knew about the new Communist rule,” said Fonn.

Enlightening their readers

The weeklies were far from just sober reading, however.

“They were often marked by pathos and a familiar tone between writer and reader,” said Fonn.

She calls the genre "commentage," a mix between commentary and reportage, because even although the writers described events, they would also often take a clear position.

At the same time, information remained central to the content. Weeklies were concerned about being didactic, which is how Allers described itself. The word did not have the negative connotations it has today. It simply meant to educate.

Weeklies for women, newspapers for men?

And perhaps it was through these weeklies that women kept up to date, Fonn said, because they were probably much less likely to read newspapers than men. Based on their content, it seems clear that the newspapers of the time were written by men for men, while the weeklies mainly targeted women.

Brita Ytre-Arne, a media researcher and associate professor at the University of Bergen, is not entirely convinced that women rarely read newspapers.

“I would certainly think that when there were newspapers in the home, they were also read by women,” Ytre-Arne said.

“Although the newspapers at that time were especially directed towards men, they would reach everyone. That also characterized the early weeklies— most of the content was for the mother, a little was for the father and there was something for the kids,” she added.

“But I can imagine that magazines written especially for women would ensure that important issues were raised there, too,” Ytre-Arne said.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no