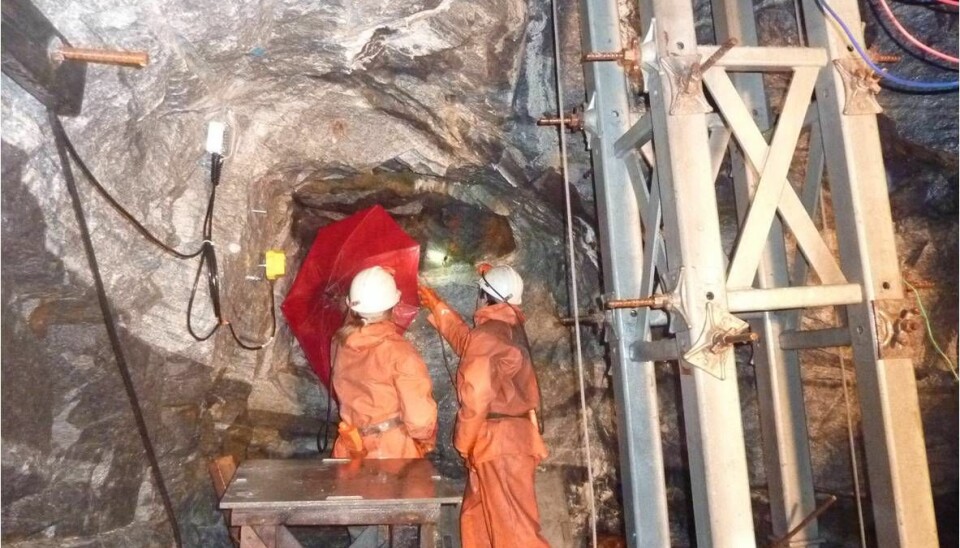

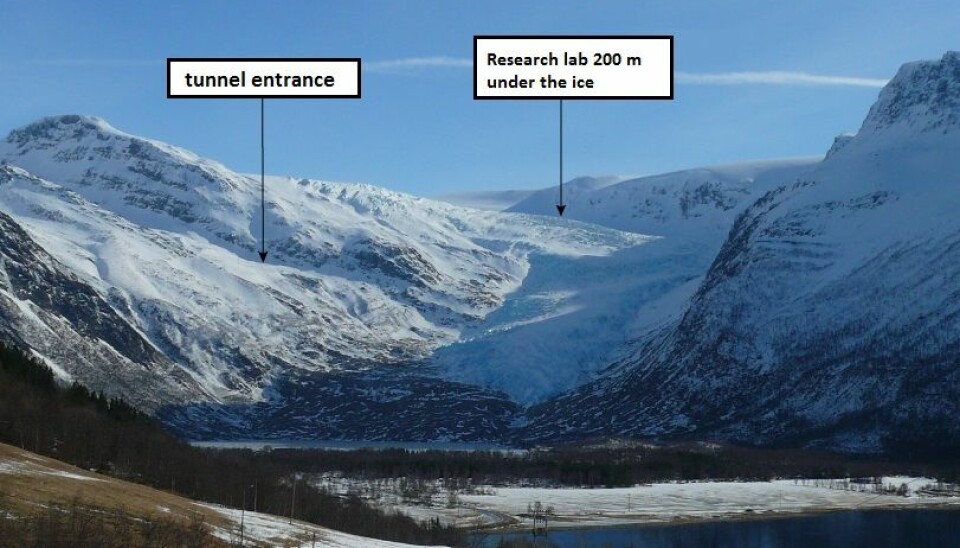

Wet research two hundred metres below a glacier

A group of scientists is currently working in what is called the world's most claustrophobic laboratory. They are studying glaciers, while blogging for ScienceNordic.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

In a tunnel system in the Norwegian mountain scientists have direct access to the bed of the glacier, under 200 metres of glacier ice.

An international group of scientists are now working in the sub-glacial laboratory, and they are blogging for ScienceNordic directly from under the ice.

Read their sub-glacial blog here

"The glacier laboratory provides a unique opportunity to do glacier research while actually inside the glacier," said Miriam Jackson at the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) in an article on ScienceNordic in February.

The sub-glacial research gives scientists new information about how glaciers move and fills in the gaps in the knowledge about the impact of climate change on large ice sheets such as Greenland and Antarctica, according to Jackson.

But working in the laboratory is not without risks.

"It can feel rather strange to know that while you are working deep in the ice tunnel the weight of the glacier above is gradually shrinking the tunnel. If you are not careful and keep one eye on the time, then you can end up being trapped in the ice", said Jackson.