Justifying gender equality through Islam

Young Norwegian Muslims are more liberal than their parents’ generation when it comes to equality and homosexuality, but both groups find support for their view in Islam, according to a new study.

This article was originally published on Kilden - Information and news about gender research in Norway. Read the original article.

According to theologian Levi Geir Eidhamar, young Muslims in Norway largely support prevailing equality ideals, and many base their arguments on Islam in their defence of equality. In his PhD thesis, he has interviewed twenty-four young Norwegian Muslims about gender roles and homosexuality.

Close to prevailing attitudes

According to a survey carried out by the research institute Fafo in 2016, attitudes among youth with immigrant background differ partially from those of the majority population. However, the general trend is that the gap between their own attitudes and the prevailing attitudes of the majority society is gradually diminishing, especially when compared to the general attitudes of the parents’ country of origin. Most indicators showed that Norwegian minority youth’s attitudes on equality issues are close to the prevailing ideals. Attitudes on homosexuality are far more conservative than those of the majority.

Theologian Levi Geir Eidhamar has made the same findings in his in-depth interviews of young Norwegian Muslims, as demonstrated in the article “Spenningsfylte endringer – Holdninger til kjønnsroller og homofili hos kristne og muslimer i Norge” (‘Suspenseful changes – Attitudes to gender roles and homosexuality among Christians and Muslims in Norway’). The interviews were carried our as part of Eidhamar’s PhD thesis.

Affected by culture

In his article, Eidhamar compares the relation between general changes of attitude in society and changes in religiously founded attitudes among Christians and Muslims. The credibility of religiously founded attitudes’, and to what extent these appear meaningful, are naturally influenced by the larger social contexts within which such attitudes exist, according to the researcher.

“We’re all affected by the culture surrounding us – a Norwegian humanist is also affected. It would be strange to claim anything else.”

Fafo’s survey involved youth with background from various different countries, whereas Eidhamar has interviewed youth with Muslim background. He has first and foremost been interested in how these young people relate to and interpret religious texts and regulations concerning homosexuality and gender equality.

Ideals interpreted differently

“As a researcher, I’ve been interested in the connection between what you may call Islamic ethics and Muslim moral. With this, I mean the connection between theory – what the texts say – and how these actually come to play in people’s lives. I am also interested in the relationship between first and second generation immigrants in Norway and how the culture and norms in society affect religious interpretation.”

Eidhamar has also conducted interviews with Muslims in Indonesia as part of an ongoing research project, and he has observed the way in which religious ideals are interpreted differently from society to society.

“If you ask Muslims in Indonesia and Norway what ideal gender roles entail you will get very different answers – but everyone will have the opinion that their own interpretation represents the genuine and true Islam.”

Life after death

He emphasises how the idea of what is good varies from society to society.

“When you are culturalised and raised in Norway, gender equality is considered a benefit. Gender equality is then regarded as an important value within the true Islam. In Indonesia, however, characteristics such as obedience, order and harmony are commonly regarded as significant values. It is considered important by many that the wife is submissive to her husband. This is considered important for the afterlife, whereas for Muslims in Norway, gender roles are something that concerns the here and now.”

“Does this mean that they are not as preoccupied with the afterlife as their parents’ generation?”

“It varies a lot. Some Muslims in Norway are highly preoccupied with the afterlife, whereas a major group consists of relatively secular Muslim youth who are less interested. Then there are some who live apparently liberal lives with alcohol, boyfriends and girlfriends and so on, but at the same time feel guilty and fear that they will be punished for their lifestyle in the afterlife.”

Influenced by Norwegian attitudes

According to Eidhamar, young Norwegian Muslims are influenced by Norwegian attitudes to equality in their religious interpretation.

“The majority of the young people draw on equality ideals in their interpretation of Islam. This reflects general attitudes in Norwegian society.”

However, the respondents in Eidhamar’s study do not necessarily agree that this is the case.

“To them, this is not about Norwegian values; it’s about the true Islam. They are sometimes discouraged by their parents’ religious interpretation, which they often describe as characterised by the culture of their country of origin. The young people claim that their parents are ‘blind to think this is Islam’, and that by going back to the sources – the Quran and the hadiths – they are the ones who know the true Islam. Yet at the same time these young people might be blind themselves to how Norwegian values affect their own religious interpretation.”

“How did you proceed in order to find interviewees?”

“I have made use of my own network various places in Norway, and I’ve also been open to all kinds of people. I talk to people on the subway, in cafes, in Mosques, everywhere. But I have been careful to find people of various ages, education, gender, and not least degree of religious practicing. If you only find your respondents in the Mosques, you will only get one segment, namely those who are openly practicing their religion. You also need to find the Muslims who never visit the Mosque. It is important with as much diversity as possible.”

Christianity and homosexuality

Eidhamar compares the changes in Muslims’ stance on gender equality and homosexuality with the changes that have taken place among Norwegian Christians over the last century.

“Attitudes to gender roles were the first to change, and then followed the attitudes to homosexuality. The fact that gender came first is probably not so strange. Women are a large and visible group in society, whereas homosexuals are a minority and often less visible,” he says.

When it comes to attitudes to both gender roles and homosexuality, the trend has generally been that religiously founded, conservative attitudes have been challenged by changing views in the greater society. For instance, the Norwegian Directorate of Health recommended to decriminalise homosexuality in 1954, whereas the Church argued that homosexuality was a ‘societal danger of global dimensions’, and contributed to ensure that decriminalisation didn’t get the majority vote in the Norwegian parliament.

The rapid change in the general society’s attitude after 1972 (when homosexuality was finally decriminalised) challenged the prevailing restrictive religiously founded attitude of the time, Eidhamar writes. “At the same time, new ways of understanding the biblical material have appeared” that have contributed to legitimise more accepting attitudes among Christians.

Conservative view on homosexuality

Eidhamar found new ways of interpreting religious material among the young Muslim respondents that he interviewed for his PhD thesis.

“Nearly all the female and the majority of the male respondents fully supported the equality ideals that characterise the prevailing attitudes in Norwegian society. This affected both which sacred texts they highlighted and how they interpreted these texts”, he writes.

Among Eidhamar’s respondents, the view on homosexuality was generally more conservative than the view on gender equality. Even among conservative Norwegian Muslims, however, very few are of the opinion that homosexuality is something that should be penalised by the state.

“The majority of Norwegian Muslims with conservative attitudes would say that homosexuals living together will be punished in the afterlife, but not that they should be punished here in this life,” he says.

In another article titled ‘Rett kontra godt? Holdninger og resonnementer blant unge muslimer i spørsmål om kjønnsroller og seksualitet’ (‘Right versus good? Attitudes and reasoning among young Muslims concerning gender roles and sexuality’), Eidhamar writes: “[A]lmost all the heterosexual respondents supported a moderate conservative view.” Among four homosexual respondents, two supported a religiously based attitude according to which homosexual relationships were accepted. The other two thought that homosexuals should live in accordance with their sexual orientation “despite their own view that it breaches with the Islamic norms.”

“People with minority background in general, and Muslims in particular, often have the experience of being portrayed as ‘the unequal others’ and of being used as a contrast to equality as a ‘Norwegian value’. Do you see a risk in putting ‘Norwegian’ attitudes to equality, as they are today, as a norm for other groups to be measured against?”

“I see the problem, but at the same time this is precisely why it is important for many in the second generation to emphasise that they, as Muslims, fully support the equality ideals that we find in Norwegian society. Young Muslim girls are tired of and provoked by the stereotype in which they are portrayed as ‘suppressed’.”

Becoming more liberal

According to sociologist Jon Horgen Friberg, who is responsible for the Fafo-survey previously mentioned, many minority youth have much more negative attitudes to homosexuality than young people without immigrant background.

“But the development is definitely heading in the direction of more liberal attitudes also among these young people, particularly when you take into consideration that many of them come from societies in which most people completely reject homosexuality,” he says.

In Friberg’s survey of attitudes to gender equality the respondents were primarily asked questions concerning education and work life.

Is there a danger that problems related to issues such as social control and sexual autonomy are no longer observed in this type of surveys?

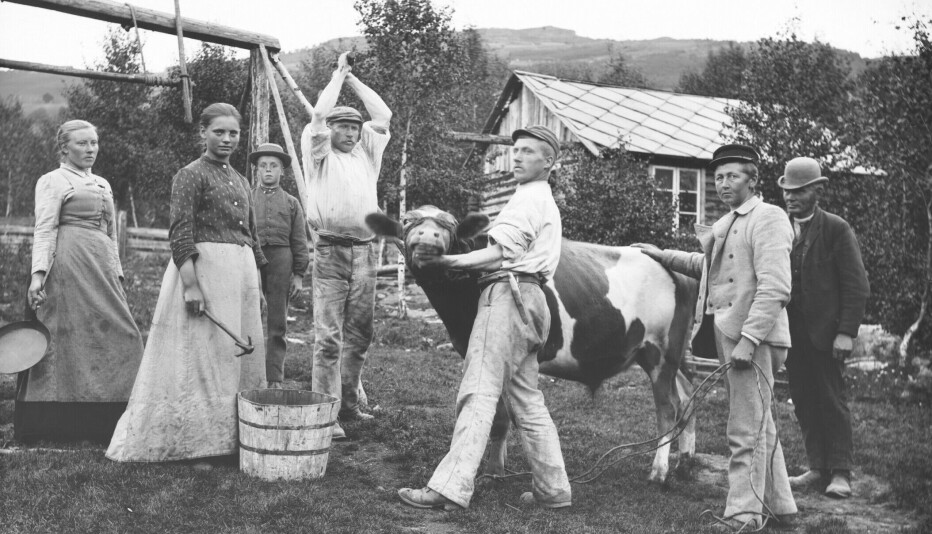

“I think you’re right that attitudes to gender equality in education and work life change much faster than attitudes to gender equality in terms of personal autonomy, sexuality, and ‘chastity’. But the ‘shameless girls’ (see photo above) demonstrate that changes are happening here too. Social change takes time and rarely happens without a fight.”

Translated by: Cathinka Dahl Hambro