Testosterone improved women’s sense of direction

But they didn’t reach their target destinations any quicker.

Some men like to joke about women’s abilities to parallel park cars or find directions. Although there are plenty of notable exceptions, men tend to navigate better and find more effective routes than women do.

Men are also better at picturing how a building or another object would look from various angles ― their ability to perform mental rotational tasks.

“Women are not going around befuddled, unable to find their way. But they often are less effective at such tasks than men are. These are the two cognitive areas where the gender differences are greatest,” says Professor Asta Kristine Håberg at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s (NTNU’s) Department of Neuroscience. She is the director of CIUS, the Centre for Innovative Ultrasound Solutions.

Sex hormones appear to play an important role in establishing and maintaining this difference, a study indicates.

So researchers at NTNU decided to give testosterone to healthy women to see if it had any effects in this capacity. The study was recently published in Behavioural Brain Research.

Young recruits

The researchers recruited 53 healthy, young women for the experiment. These were randomly divided into two groups. Each woman in one group was given 0.5 mg testosterone under the tongue. The other half of the women received a placebo.

It was a double-blind test, meaning that neither the researchers nor the women knew what they were getting.

Would the little dose of testosterone give the women better spatial abilities and sense of direction?

Navigating

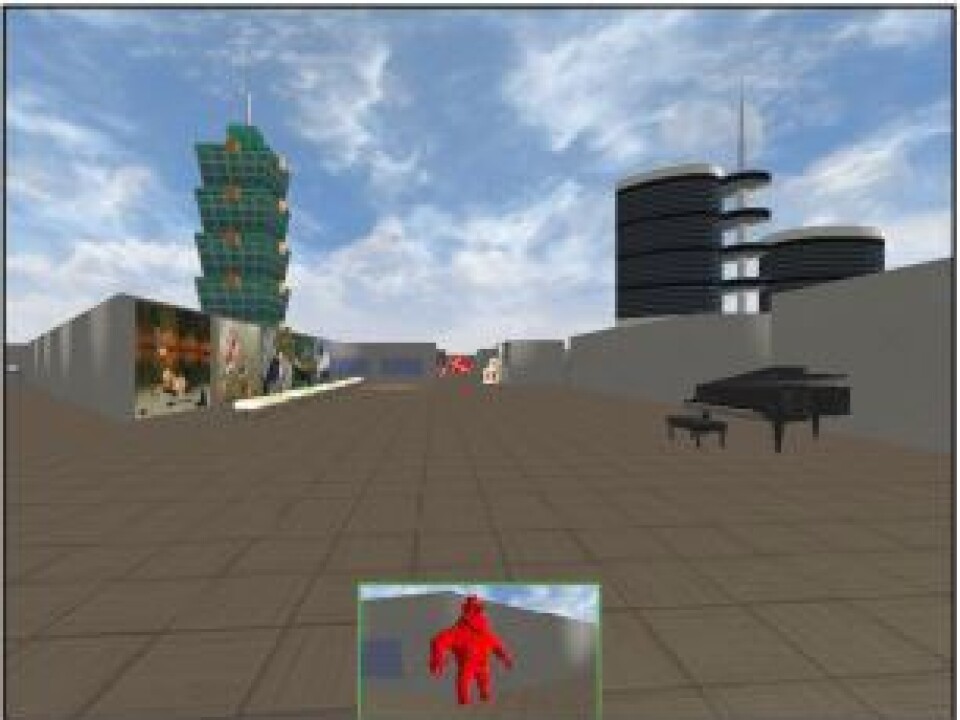

The women initially got acquainted with a computer-game sort of office space. Then they were supposed to navigate in this virtual locality while undergoing a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scan. They were asked to find the fastest route from where they stood and reach a target in the virtual landscape.

This environment had 76 indoor landmarks and six outside the office windows. None of the women had any previous experience with computer games that have such features.

“They were given no other instructions other than to try and find the fastest way to various spots,” explains Håberg.

They had to place a joystick on their stomachs and manipulate it to reach the given goals. The researchers studied which routes they took, how fast they found the goal and how often the women completed the task within the time limit.

Following the fMRI the researchers measured the participants’ mental rotation skills and tested how well they understood the virtual office layout.

Seven of the participants became so nauseous they had to quit and four failed to acquaint themselves with the virtual setting sufficiently to take part in the fMRI.

Only 42 women completed the entire experiment.

Better sense of direction

The women who had received testosterone were better at navigating among the landmarks in the virtual office locale. They also had better mental rotation abilities than the placebo group.

But that was not enough. The testosterone group did not get to the target point any faster. They did not choose shortcuts, nor did they find more of the landmarks that were partial targets to reach along the way.

“We don’t know why this is,” says Håberg. But the researchers offer a few interpretations.

Less nauseous

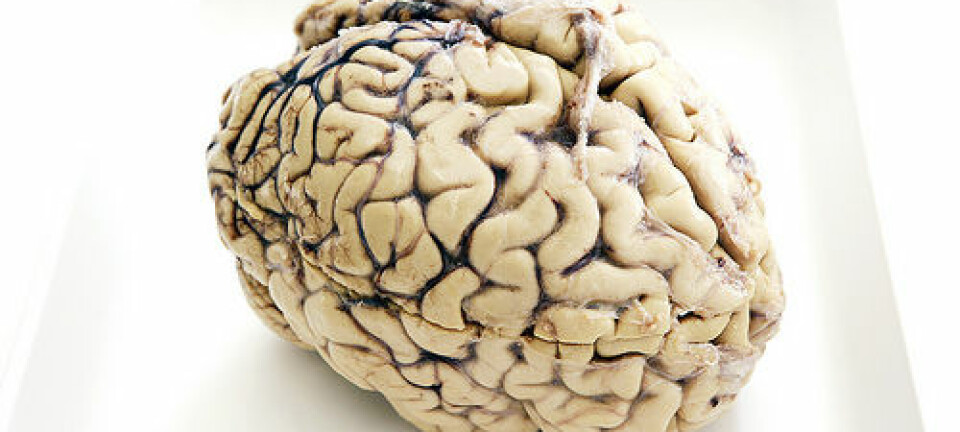

As the women who were given testosterone navigated successfully they showed much more activity in the medial temporal lobes. This is a region of the brain that is important for the sense of direction.

The researchers also found that the activity in this brain area increased when more testosterone was found in their bloodstream.

The women who were given testosterone were also significantly less nauseous during the experiment than the control group who received a placebo.

“It is well known that nausea is linked to hormones, for instance many women have problems with it during their pregnancies,” points out Håberg.

Why didn’t they get to the goal faster?

Although testosterone had a positive effect on sense of direction and brain activity, the women who were given it were no better at reaching designated sites. Why?

“The results show that testosterone only has a limited effect on the sense of direction but the reason for that is still a mystery. It might be that testosterone has more of an impact on certain areas of the brain better than others.”

Or perhaps navigation is a complicated form of behaviour which is largely based on what one has learned,” suggests Håberg.

Even though the women who got a dose of testosterone were better at knowing which direction they should go, they still refrained from taking shortcuts to the designated places.

“This can have something with the women’s learned habits. People prefer a strategy that is known to work,” says Håberg.

The researchers knew from earlier studies that men often take shortcuts to reach destinations, whereas women tend to follow the main roads, even if it takes longer.

“It could be that the women do not trust ways of navigating to a destination other than the strategies they have learned,” she says.

Not simply gender differences

Having a good sense of direction is not simply determined by gender and it is uncertain whether men really have an advantage here, according to certain studies.

“Age plays a role as well. Older people generally have better spatial cognition than younger persons. They are better at estimating distances and are less reliant on the use of landmarks,” says brain researcher Charlotte Alme at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

Brain researcher Kaja Nordengen at the University of Oslo has researched the part of the brain associated with sense of direction. She does not think we can ascertain that men have a better sense of direction than women do. In an article published in Norwegian on the website of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), studies are mentioned that contradict this male advantage as well as ones that confirm it.

“There has been a lot of disagreement in this subject. But on the whole, we see a tendency for women to have a fear of losing their way. They lack self-confidence regarding sense of direction. But when actual tests are made and women’s and men’s senses of direction are compared, both have generally done equally well,” she said in the NRK article.

Nordengen also thinks that sense of direction can be better or worse, depending on which role an individual opts for when facing a task.

Navigation and rotation

Navigational ability is linked with the ability to solve tasks involving conceptualisation of objects from different angles.

On average men score higher than women in such assignments but the biological mechanisms which explain this are still uncertain.

That said, testosterone levels seem to play an important role. In general, increased levels of the hormone are moderately linked with better mental rotation abilities among women.

But testosterone has two effects on the brain. The organisational effects start in the embryonic stage and result in permanent changes in the brain. The activated effects vary more depending on hormone levels at any given time.

Researching gender differences in the brain

“We know that finding one’s way depends on an interplay between various regions of the brain. This study could indicate that testosterone might not work as much in all these regions,” says Håberg.

“It might be that a supplement of testosterone has only a very fleeting effect, or that it first starts to work later on than the time-frame used in our study. Unfortunately we don’t know the answers to that,” says Håberg.

------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling