Design may alter gender stereotypes

Subconscious attitudes towards women and men affect design. According to researcher Nina Lysbakken, designers need to be aware of their own power to shape ideas about gender.

This article was originally published on Kilden - Information and news about gender research in Norway. Read the original article.

Do designers have power to affect our attitudes towards gender and diversity? Yes, says Nina Lysbakken, PhD research fellow at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO).

“I’m interested in how design is connected to the designer’s world view. Fundamental thoughts and ideas may be expressed through all kinds of things from illustrations and newspaper titles to online design concepts,” says Lysbakken.

Lysbakken studies the opportunities related to the design of online comment fora, and has recently published an article about gender and power in newspaper and magazine design. According to her, stereotypical representations of women in the media are the result of more or less conscious attitudes.

Beautiful women, brave men

“Take for instance the photos in women’s magazines. Here, women are often represented as stunningly beautiful, sweet and kind, or sexy and posing. This is also the case when they have jobs that require them to be determinate and to make brave choices,” she says.

In order to illustrate her point, Lysbakken uses a photograph in her article taken by the photographer Morten Krogvold of the public debater Kadra Yusuf.

“The photo of Yusuf communicates so much through the way she is represented; as determinate, critical and brave. The photograph is in black and white, taken from the side, and she appears serious, keeping her back straight,” she says.

“For me as a designer, it is not as easy to find a good illustration photo of a female leader looking cynical and arrogant, as it is to find a photo of a similar looking man. This has to do with both how photographers look at the world and with picture databases. There are many stages in the process that affect how gender is represented in our time.”

According to Lysbakken, the designer has the power to influence the culture to be more or less gendered.

“This applies to both boys and girls. The means used to appeal to boys are equally as gendered as those used to appeal to girls,” she says.

In her article, Lysbakken demonstrates how different layouts substantiate different qualities in one and the same person. By adding a black frame and tight letter fonts to the photo of Kadra Yusuf, we get a different and more strict impression of her than what we would get if the same photo were framed in pink with ornate letter fonts.

“In this article, I wanted to alter the space in which we talk about gender,” she emphasises.

“For instance, this may be done through the use of pictures telling a different story than the one that reinforces our stereotypical ideas: A crying boy or a skateboarding girl wearing a hijab.”

A different women’s magazine

Lysbakken emphasises that designers are not neutral. This is demonstrated in a project she conducted with design students at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, campus Gjøvik.

“I told the students to make a different women’s magazine, which was certainly not an easy task,” she says.

She points to the fact that women’s magazines are often highly stereotypical. Their contents are always based on topics such as make-up, fashion, health, family and diet.

“Why don’t we have women’s magazines that are primarily about topics such as outdoor life, sports or history? Although many of these magazines define themselves as fashion magazines, they are known as ‘women’s magazines’. Consequently, they contribute to defining what women’s interests ought to be.”

Lysbakken’s students were assigned to figure out other topics and other ways to present the material in the magazine.

“And to find other types of women than those who are normally presented in such magazines, who are first and foremost representations of the prevailing beauty ideal,” says Lysbakken.

“One group of students in particular managed to think outside the box. They came up with a magazine concept based on people instead of topics. The idea was to present curious and courageous women, with the following question in mind: What can we learn from these women?”

Diversity within the design team

According to Lysbakken, designers are often unconsciously inspired by a wide spectre of sources of inspiration, some of them personal.

“Some women need other ideals than what we find in traditional women’s magazines. We therefore need a greater diversity of ways to present women and women’s stories,” she states.

In the same way, some men may perhaps need help from popular culture in order to dare to be vulnerable.”

She points out that the designers’ gender and cultural background play a significant role in shaping the product.

“As designers, we often unconsciously choose images that represent ourselves and end up making designs that look like us. Diversity within the design team is therefore important for the design to appeal to as many as possible,” says Lysbakken.

“Take for instance Apple’s health app, which did not include menstruation when it was launched, or seatbelts that are not designed to fit pregnant women. Or reality glasses that have made numerous women nauseous.”

Lysbakken believes that these designs would have looked differently if women had been part of the design team.

Gender plays a part

According to Astrid Skjerven, professor of product design at AHO, gender is a significant factor within design, both when it comes to design, the production process and consummation.

“Women and men behave differently and have different needs. This will affect all stages in the sales process,” according to Skjerven.

“Who the designers are, for whom they design, and to what extent the design is made to accommodate women or men is therefore highly significant. This has not been sufficiently emphasised in research.”

She points to the typical example of girls choosing pink and boys choosing blue both when it comes to clothes and toys.

“The designer should reflect more upon her or his own influential power and what she or he can do in order to find new ways to relate to gender.”

Skjerven emphasises that there is no established tradition for research on gender within design. She thinks this may be because the sector has been, and still largely is, highly male dominated. Despite the fact that there are some trendsetting female designers in Norwegian design history, such as Frida Hansen and Grete Prytz Kittelsen.

“Many Norwegian female designers were married to men who were also designers, and used their knowledge to assist their husband rather than making a career on their own,” says Skjerven.

“Hansen and Prytz Kittelsen are exceptions to the rule. Frida Hansen did this because she had to provide for her family and Grete Prytz Kittelsen because she represented her fifth generation within a family enterprise.”

“Are there still more boys among the design students?”

“No, today there are approximately half and half boys and girls. But we’ve observed a tendency that they choose different directions within the discipline: Boys often choose industrial or technical design whereas girls choose service design.”

May affect online debates

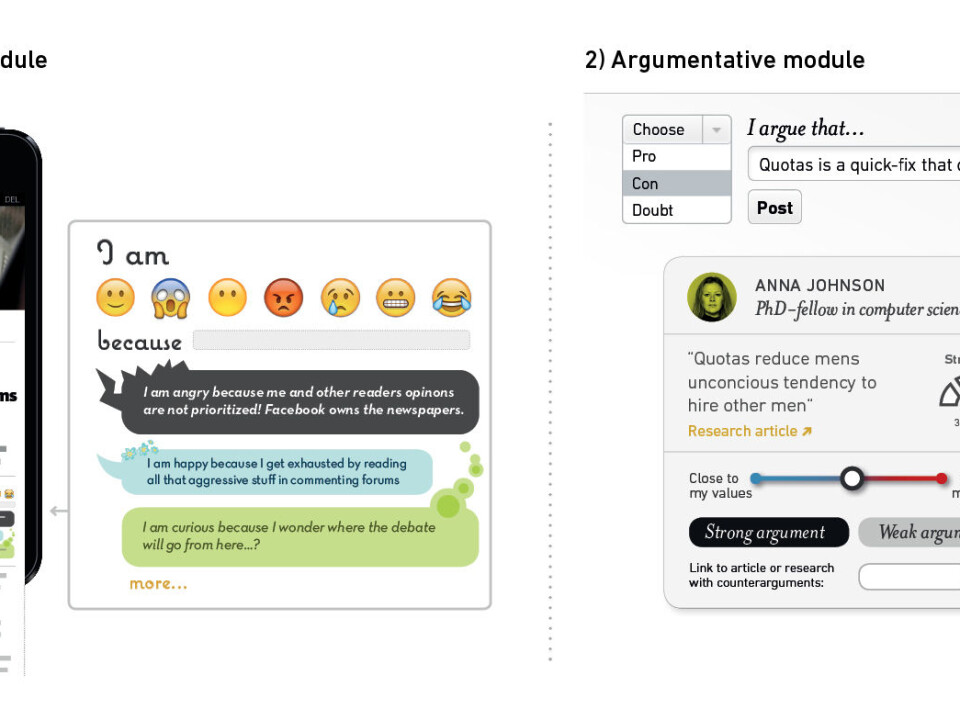

Nina Lysbakken’s PhD thesis primarily looks at how to design online comments sections, and to what extent the design creates room for dialogue. Among other things, she has designed concepts based on how women and men discuss differently in various closed Facebook groups.

“In certain women’s fora, it seemed as if the fundamental goal behind the debate was to learn rather than to win the discussion.”

Far more often than in the online newspaper fora, she noticed that the women openly expressed doubt and insecurity and that they referred to others with more competence than themselves on the topics under discussion. These fundamental goals and ways of expression became the cornerstones of the design.

According to Lysbakken, the designer can partly affect what types of dialogues take place online.

“I think the online comments section designs contribute to the shaping of the public debate both in terms of form and content. There is little awareness around this today,” she says.

Challenges our own ideas

Some researchers argue that all the things we surround ourselves with in our everyday lives affect us and that they may enhance or contradict our perception of ourselves and our world. Lysbakken consciously applies design methods in order to challenge her own ideas and push them in a certain direction.

“By using artistic styles and images of women and men that refute stereotypical perceptions of women, men and culture, as a designer you may contribute to changing these perceptions.”

According to her, the designer’s job is also to balance this against various perceptions.

“It is important to be aware of the fact that our own perspective is limited compared to the users’. We all have different perspectives, and I only communicate one through my design, so it is impossible for me to reach everybody.”

According to Lysbakken, design can only become better if the designers are conscious of their own perspectives and challenge these. In this way, the designers are better equipped to challenge stereotypes and contribute to increased diversity.

“Is gendered design more marketable?”

“Yes, I think the business sector experience more interest in gender stereotypical products, which isn’t strange after all. If you are supplied with princess products from you’re a little girl and you constantly hear how pretty you look in pink, the demand for gender stereotypical products will increase,” she says.

“But designers have also contributed to making this attractive and interesting, just as they contributed to the inclination to buy iPhones and mobiles that were not previously considered trendy. There is no reason why they shouldn’t be able to do this again, with other or different ideals that may challenge today’s powerful ideals and provide more options.”

Lysbakken emphasises that helping businesses sell their products is only one of the designer’s many tasks.

“We can affect and govern people’s taste and inclination to buy. And this is something we should take seriously and be much more aware of.”

Lysbakken wonders why designers don’t have more ambitions when it comes to their power to change and affect the visual culture in which we live.

“I think designers have very low professional self-esteem. We’re not used to argue for our own significant role in society. But there is much power in design,” she says.

Translated by: Cathinka Dahl Hambro