Have Norwegian youth become more tolerant of the use of political violence?

A new study indicates that an increasing number of young people have become more willing to support violence to create awareness about an issue or to change our society.

Supporting the use of violence to change society is an essential element in violent extremist environments.

Researchers from the Center for Research on Extremism (C-REX) have now investigated how Norwegian adolescents respond to such questions.

More than 2,500 upper secondary school students have responded to the survey which asks a multitude of questions about extremism.

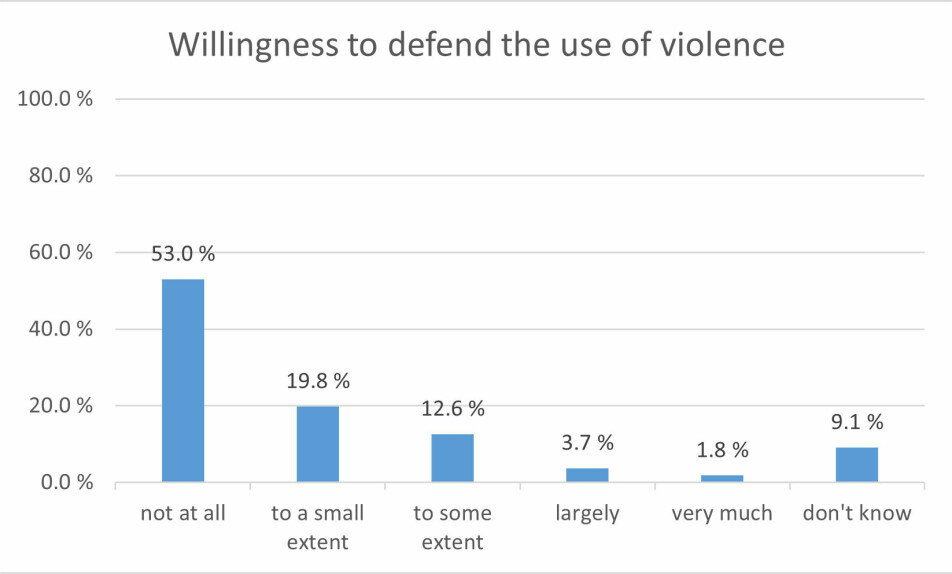

One of the questions asked in the survey is whether someone using violence to gain attention for an issue or to create social change in Norway can be defended.

Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they believed this, from "not at all" to "very much".

Most reject violence

Over half of those between the ages of 16 and 19 categorically reject the use of violence to gain attention or bring about social change in Norway.

A small group is willing to defend the use of violence.

5.5 per cent say that they are largely or very willing to use violence to create attention for a cause or change Norwegian society.

A change since 2015

Similar questions were asked in the survey Ung i Oslo (Young in Oslo) in 2015 (link in Norwegian).

At the time, 3 per cent of adolescents in the capital defended the use of violence.

Now students at upper secondary schools all throughout Norway have answered some of the same questions.

Most of the respondents live in Eastern Norway. A slight majority of them are girls.

Fewer completely reject the use of violence

Compared to the study from 2015, there is only a small increase in those who show some support for the use of violence.

“It's good that there aren’t more, even if the 144 who defend it are far too many,” researcher Håvard Haugstvedt said when he recently presented the findings of the report.

“What is less positive – and a little worrying – is that the proportion who categorically reject the use of violence is significantly lower now than in 2015,” he said.

Unclear what the support entails

Over 30 per cent say that they defend violence to a small, or some extent in the new survey.

This is almost double the figure presented in the 2015 survey.

The researchers have not specifically asked what their support for the use of violence entails.

Haugstvedt believes there could be many possible explanations.

“It may be that one is willing to use violence to create changes in relation to climate issues or animal protection, for example,” he says.

What has caused the change?

The survey was carried out during a period of extensive lockdown in Norway because of the Covid pandemic.

“Although the response rate is somewhat low, it is gratifying that the report has produced some results that are relevant to the authorities' work to prevent extremism in society,” department director Toril Melander Stene of the Norwegian Ministry of Labour said when the report was published.

She believes there is reason to question why fewer categorically distance themselves from defending the use of violence than before.

“Is this change due to unrest, climate change in the world and terrorist attacks that we have witnessed nationally and internationally? Has the period of closure and isolation from the community affected the result?”

She hopes that future studies will provide answers to these questions.

Clear patterns

There are clear patterns among those who defend the use of violence.

They are mostly boys.

Several of them have a lower degree of trust in other people.

There is also an over-representation of people who have experienced discrimination from private individuals and public authorities.

Many come from parents who were born in countries other than Norway.

A majority identify that they believe in Islam.

Also, several have used strong drugs and have been in contact with the police.

The school's teaching matters

There is, however, another connection that emerges more strongly in the researchers' statistical analyses.

They see that what matters most is whether the student has been taught about critical thinking and democratic values at school.

This result is encouraging, Haugstvedt argues.

“This means that there is something in the work schools are doing today that is helping,” he says.

No simple connections

This does not mean that if a student receives such teaching, the risk of radicalisation disappears, he warns.

“Extremism is connected to so much more than just what takes place in the classroom and the local environment. It is also linked to international lines of conflict and global issues. It is unrealistic to place all the responsibility on the schools,” he says.

Nevertheless, this connection they have found is interesting and uplifting.

“This should be measured in future studies that run over several longer periods of time. This study only provides a snapshot,” Haugstvedt concludes.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

Håvard Haugstvedt and Tore Bjørgo: Ungdom og ekstremisme i 2021 - En studie av ungdommers vurdering av ekstremisme og forebygging i Norge (Youth and extremism in 2021 - A study of adolescent's assessment of extremism and prevention in Norway), C-REX report no. 2/2022