In conversation with Norway’s home-grown extremists

Siri Høyem Kristiansen from OsloMet has visited Norwegian prisons to interview rebel fighters returned from Syria. She was surprised by what she found.

Few researchers have talked directly to rebel fighters returned from Syria.

So when Siri Høyem Kristiansen visited Norway’s ‘most dangerous men’ in prison, she expected them to act like religious extremists. The reality was rather different.

“I met men who were courteous and attentive and concerned about mutual respect. Take the handshake as an example: Of all the people I interviewed, only one wouldn’t shake my hand. But after we had talked for hour after hour, he said: ‘Siri, I think we should take each other’s hands.’”

At times, she was served homemade pizza and soda by a rebel fighter. Several people hugged her after the interviews.

Home-grown radicalisation

Kristiansen was a master’s student at OsloMet and part of a large research project called Radiskan, or Searching the Unknown: discourses and effects of radicalization in Scandinavia, which has now ended. The project goal was to learn more about how radicalisation could be prevented at the ground level in Scandinavia.

Therese Sandrup of the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment led the project, which included extensive fieldwork in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark.

“The goal has never been to find a recipe for prevention, or a cure for radicalisation. But hopefully, our work will provide a basis for reflection and greater awareness about the kinds of measures we undertake,” she says.

Read More: Faith is a private matter for young Norwegian Muslims

No consensus on common characteristics

When the project started, municipalities and local residents were under a great deal of pressure to cooperate with the police in finding potentially radicalised people.

Especially after the terrorist attacks in Madrid and London, the focus was on ‘home-grown radicalisation,’ meaning radicalisation that had grown from within a country’s own borders.

A great deal of time and effort was spent tracking people who were thought to have been radicalised. And to see whether they had anything in common.

“But there was no consensus on what it means to be radicalised,” says Sandrup. “There is a myth that all violent extremists have been through a violent radicalisation process. But research shows that’s not true.”

Radicalisation is about emotions

Researchers know that in most cases, radicalisation is a group phenomenon. It involves friends, colleagues, and relatives in social networks that affect each other. And it is often linked with situations that people experience as unbearably unjust or deadlocked, says Sandrup.

Radicalisation is about strong emotions, which can be contagious and must be taken seriously, she said. Sandrup believes that many more people need a way to vent their feelings.

“The need to ‘do something’ about a situation that feels unfair is underestimated in prevention work. Perhaps people's engagement with an issue should be channeled towards democratic arenas, where frustration and anger can be discussed and aired,” she says.

Read More: Justifying gender equality through Islam

Extremists are not living on the street

Siri Høyem Kristiansen is familiar with many of these issues, and the potential for substance abuse, violence, and crime out on the street. She worked for a number of years for “= Oslo”, which publishes a street magazine for people to sell as a way to earn money.

When the first rebel fighters travelled from Norway to Syria, there was a lot of speculation about who these young men were. A number of people believed that they were affiliated with street criminals.

"But I have never met people on the street with extreme beliefs or who had converted to Islam. It made me curious,” she says.

No discussion of Syria

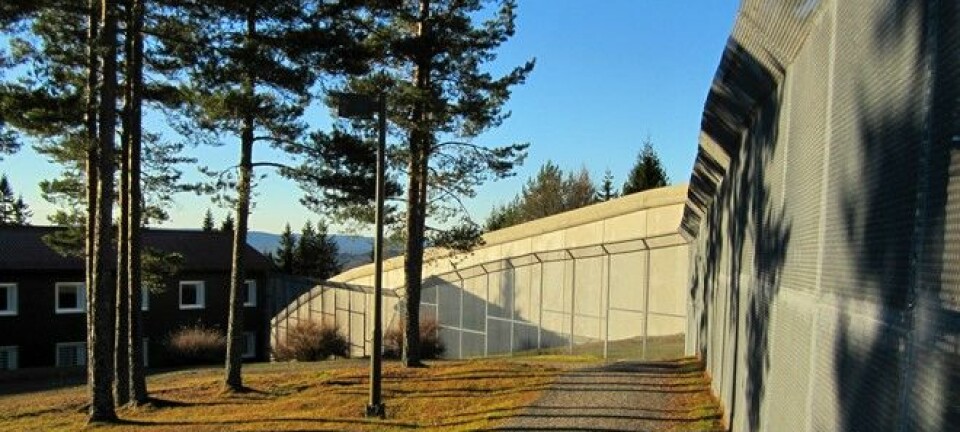

Kristiansen spent 40 hours in Norwegian prisons to interview rebel fighters. She deliberately did not ask them about what they did in Syria or other issues that could be part of a legal proceeding.

"When I started the interviews, a number of extremist groups, like Profetens Ummah, were still very active. There was an great deal of surveillance. I had to take this into account,” she said.

The fighters who went to Syria talked a lot about what it was like to come home to Norway. Most felt like heroes when they left. When they came home, they found that people perceived them as if they were monsters and something to be afraid of, she says.

One informant said:

“In the period after I got home, I felt like I was dead, like a dead man with vultures flying over me, the Norwegian Police Security Service and the media.”

Another said, "The media portray us like monsters."

Read More: Why do Norwegian youths believe the West is at war with Islam?

Thinking differently

Norway mainly relies on punishment, but rehabilitation is also an integral part of any prison term. The thinking is that all prisoners will eventually be reintegrated into society.

But if we are going to rehabilitate this target group, we must talk to them, Kristiansen said.

"It's important that we start talking to them and not just about them. By talking to them, we can learn. That’s important in determining what we can do now and in the future,” she said.

----------------

Read more in the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no