We can close our eyes and mouth. Why can’t we close our ears?

ASK A RESEARCHER: Wouldn't it be nice if you could close your ears underwater or when you’re in noisy surroundings?

The human body has undergone a long evolution to the way it is today.

Eyelids protect our eyes and if we close our mouths, we prevent debris from entering.

Our ears, on the other hand, stay open. They can’t close like the ears of seals, rhinos and otters, for example.

Why? Wouldn't it be nice to be able to close our ears, for example when we are underwater or when we’re surrounded by a lot of noise?

We moved from water to land

ScienceNorway.no spoke with Jarl Giske. He is an evolutionary biologist at the University of Bergen.

“The short answer is that it’s been a real long time since we started our development in water,” says Giske.

About 380 million years ago, our ancestors stopped being fish and they came ashore.

Therefore, we haven’t needed to be able to close our ears like seals and other animals in the water.

Isn’t it a little stupid that we can’t close our ears though? What about protecting them against dirt and dust?

“We do fine,” says Giske.

Animals on land that have to protect themselves from dirt and dust, for example in the desert, have developed hair in their ears rather than a closing mechanism. People have hair in their ears too, the researcher says.

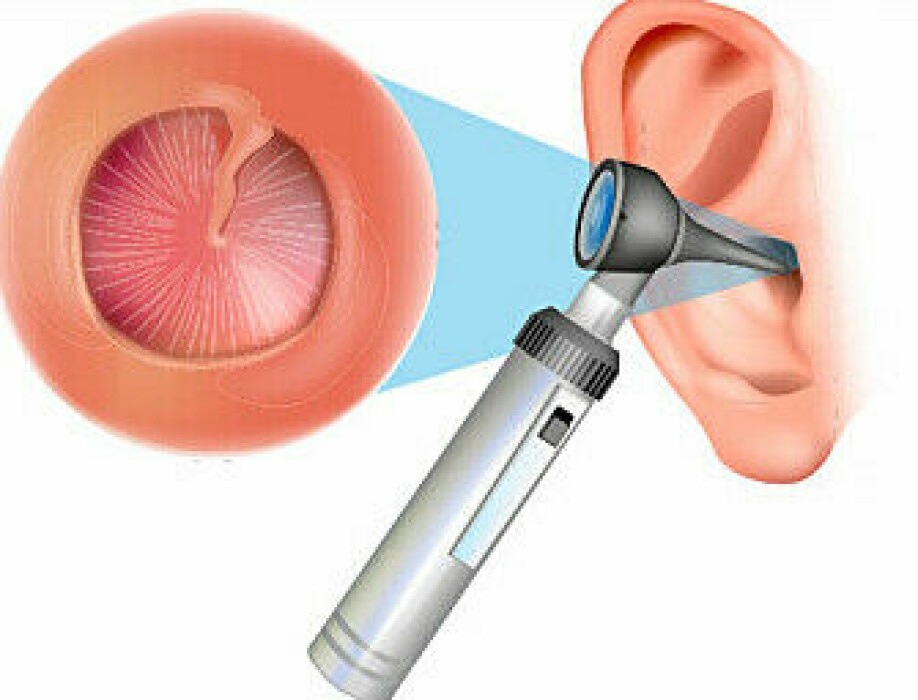

You have a membrane in your ear

So we can’t close our ears. And the hairs help. But did you know that you also have a kind of lid inside your ear?

This 'lid', or rather the tympanic membrane, also called an eardrum, keeps water, insects and dust from entering.

The eardrum is super thin, so sound still comes through, thank goodness.

“Open ears with a thin membrane means that we can always hear. And that might have meant the difference between life and death for us,” says Giske.

For example, we could hear dangerous predators and hide in time. We survived, and then we were able to have children and pass on the ability to hear well to the next generation.

Our hearing gets worse the older we get. Would it have been better if we could close our ears?

“Yes, our ears do wear out over time. And that happens even more nowadays. A lot of people listen to a lot of loud music, and it strains their ears,” says Giske.

Generations before us didn’t have headphones with loud music, which means this hasn’t affected evolution.

Seals can close their ears

Our ancestors made the move from water to land.

“Seals have gone from living on land to living in water again,” Giske says.

And so they needed to be able to close their ears. Seals don’t have outer ears like us that hang and dangle, instead they have a flap that allows them to close their ears.

“When they dive, they can close their eyes, mouth, nose and ears,” Giske says.

Hearing protection against cock-a-doodle-do

Human hearing often performs well, even when exposed to loud noises. For roosters, it's a different story.

They crow so loudly that the sound level is the same as standing just 15 metres from a jet taking off.

Belgian researchers wondered how roosters could crow so loudly without developing hearing loss.

The researchers checked to see if roosters protect their ears in any way.

They do!

When the rooster opens its beak completely to crow, parts of the ear canal closes up and thin skin covers half of the eardrum.

No ear evolution

So, our human ears have not evolved to close. And that will not be happening anytime soon either. We can still have children even if our hearing gets worse.

“A lot of animal species have better hearing, better eyesight and are faster than us. Our specialization is that we’ve learned to use tools and make aids for ourselves,” says Giske.

For example, we can use ear protection or earplugs if the surrounding noise is too loud, such as on a construction site.

In other words, we won’t be seeing any ear evolution to protect us from modern noise.

But perhaps our ability to make good aids will get even better, so that we can discover better solutions to protect our hearing.

Then maybe we’ll be able to keep the hearing we are born with for life.

Reference:

Raf Claes et.al.: Do high sound pressure levels of crowing in roosters necessitate passive mechanisms for protection against self-vocalization?. Zoology, 2018. (Summary)

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no