Our ancestors used ape tools

One skill we’ve considered uniquely human is actually ape behaviour.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

“We have known for some time that chimpanzees hunt, use stone tools and have other skills that the first humans had. What surprised us in this study was finding proof that chimps also collect food by using tools to dig up roots and tubers. We thought this was uniquely human,” says Adriana Hernandez-Aguilar.

She is a researcher at the Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis (CEES) at the University of Oslo.

Only the chimpanzees in the Ugalla area of Tanzania, where the research team conducted its study, appear to have this skill. Observations of chimps in other regions have led to the conclusion that they don’t use tools to dig for roots. The Ugalla chimps utilised sticks and branches as their digging tools.

“This finding is important for the understanding of evolution because it shows our ancestors’ activities weren’t unique for humans like we thought,” says the scientist.

First long-term study

Hernandez-Aguilar spent two years in Ugalla studying chimpanzees that live on the savannah. This was the first long-term study of savannah chimps in East Africa. More research is ongoing in the region.

Chimpanzees are great to study because they resemble us so much. Their body and brain sizes are quite similar to those of our distant ancestors 3-6 million years ago. Chimps’ social structure also resembles our everyday social life. This is sets them apart from for instance orang-utans, who lead an asocial lifestyle.

Hernandez-Aguilar finds studying chimps on the savannah especially rewarding as a means of gaining insight into our own evolution, because their environment is similar to the dry landscape where the first humans wandered around.

“Studies of these animals can teach us about how primal humans lived and survived and give us a better understanding of where we come from,” says the scientist.

Stone tools

Hernandez-Aguilar and her colleagues asserted recently in an article in Evolutionary Anthropology that current information about chimps’ making and use of tools undercuts former assumptions that the use of tools was unique for humans.

One example is the Oldowan stone tool technology that has been perceived as something that distinguished the human precursor homo habilis from apes. These tools were used in a number of ordinary activities and the earliest discovered so far are 2.6 million years old.

Hernandez-Aguilar says the oldest finds of stone tools used by chimpanzees have been dated back 4,000 years, but that doesn’t rule out that they used such tools earlier.

We know that the Oldowan tools were made by our ancestors, not by apes, but the scientist thinks the purpose of such use of tools is more important than which tools were made by whom.

“The tools were used for the same activities. So we’ll have to say that Oldowan isn’t human technology, but rather that our ancestors used ape technology.”

“They didn’t have to be any smarter than chimps to make and use Oldowan tools. That means we can no longer characterise the technology as uniquely human,” she says.

The chimpanzees that Hernandez-Aguilar studied on the savannah don’t use stone tools. In fact no chimps in East Africa do; only ones living in West Africa.

We don’t know why this is but the scientist deems it natural that different groups of a species living in different places develop separate methods that function for the group locally.

The East-African chimps used sticks, though, to dig for roots.

Tough conditions required new methods

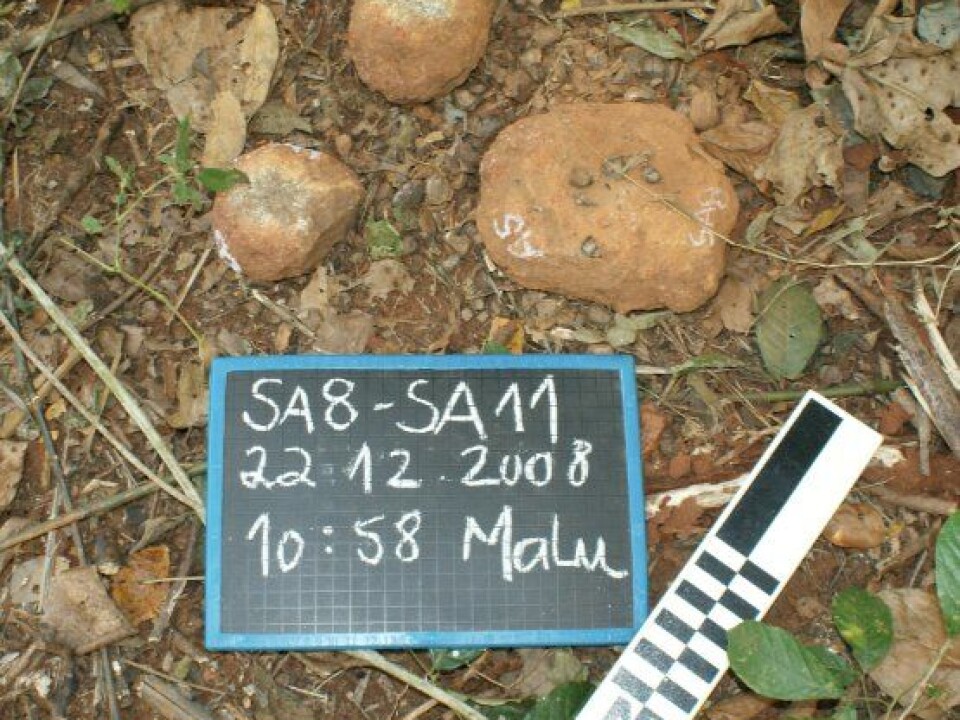

The research team in Ugalla chose a whole new method for studying the animals, an approach that mixes archaeology with traditional procedures.

“We’ve elected to use archaeological work methods, for instance viewing tools in a microscope to find out what they were used for. This has been supplemented by common procedures, such as taking DNA samples from hairs found at chimpanzee sleeping sites and from their excrement to see what they’ve eaten,” says Hernandez-Aguilar.

Studying chimps from a distance takes more time than studying the behaviour of animals that have grown accustomed to humans, but it gave the researchers an opportunity to learn about groups that are hard to approach and about which little was known.

“The harsh conditions on the savannah make it harder to study chimpanzees here than those that live in the rainforest,” says the scientist.

In Ugalla six months can pass without a drop of rain. The temperature can rise above 35° C in this dry season, which means the chimpanzees need more water at a time when there is naturally less available. These chimps need to walk further to scavenge for food so they have a larger habitat.

The density of chimps on the savannah must be less than in the rainforest because of the relative scarcity of food and water. The size of the area that Adriana and her team studied is about 80 square kilometres.

“We estimate that around 50 times as many chimpanzees live in the rainforest as on the savannahs,” says Hernandez-Aguilar.

With fewer animals in a much larger area, it’s a more formidable challenge nearing and observing them with traditional methods.

Social calls

Further analyses of the material gathered by the researchers in Ugalla will provide better understanding of the meaning of the chimps’ various calls.

“For instance we know that they have a special yell when they’ve killed a monkey and are signalling to the other chimps that food is available,” says Hernandez-Aguilar, and she gives an imitation of the call.

For the untrained ear it sounds just like the call you would normally make if you were acting the role of an ape, with an undulating and escalating screech.

“Analyses of these animals’ calls is more interesting on the savannah than in the rainforest because of the greater distances between them. So this form of communication comprises a bigger part of their daily life,” explains the scientist.

The results of the analysis of the chimp calls will be complete in about two years.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling