This article is produced and financed by University of Oslo - read more

Researcher has followed conversations on anti-Islamic online forums

In many countries, the current political opinions of different groups firmly oppose each other. A new study of two Norwegian Facebook forums shows how group discussions on social media may be pushing the boundaries.

Katrine Fangen has followed the discussions in two Facebook groups that were open when she studied them in 2017, but which have subsequently closed over the past couple of years. The participants in both groups are very negative towards Islam and Muslims.

The study was recently published in a special issue on ‘Gender and the Far Right’ in the journal called Politics, Religion & Ideology.

“In social media discussion groups, people often discuss things with like-minded people. Participants meet little opposition, which means that they might push the boundaries of what is perceived as being permissible to say”, says Fangen.

She is a professor at the Department of Sociology and Human Geography, University of Oslo (UiO), and is also affiliated with the C-REX Centre for Research on Extremism (UiO).

Dangerous by nature

According to Fangen, little research has been conducted on Facebook discussion groups where participants are strongly opposed to Muslim immigration and the presence of Islam in society. Typical characteristics found in the two Facebook groups she describes are:

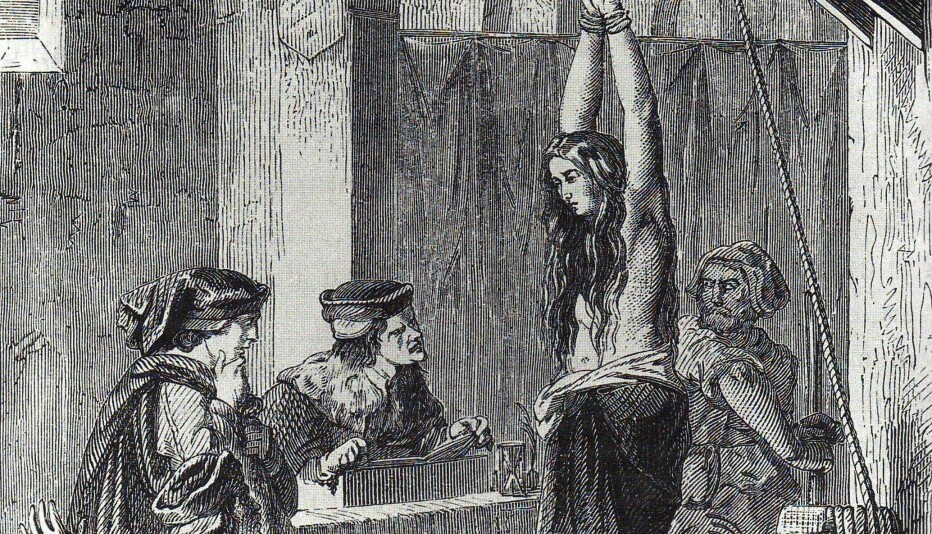

- Muslim men are often seen as being dangerous by nature.

- Norwegian, non-Muslim girls must be protected.

- Muslim women are portrayed as being oppressed, but it is expressed that they have chosen it themselves.

- Muslim women who hold positions of political power are seen as representatives of a ‘stealth jihad’.

When Muslim female politicians are the focus of discussion, the fact that they publicly support secular values does not seem to help.

“Many of those who comment in the groups express that secular Muslims are simply hiding their intentions. Therefore, they may be seen as equally threatening as more conservative Muslims”, says Fangen.

Opposition in multiple communities

Attitude surveys, some of which have been done by the Directorate of Integration and Diversity and the Norwegian Centre for Holocaust and Minority Studies, show that opposition to Muslim immigration, and also to a certain extent to Muslims as such, not only occurs in explicitly anti-Islamic communities. It is also found in broader sections of the population.

According to Fangen, a number of internationally renowned feminists have fronted criticism and opposition to patriarchal attitudes within Islam and advocated that Muslim women must be saved from oppression.

“In the Facebook groups that I have written about, this is not the case. Instead, it is argued that the women have chosen oppression voluntarily and deserve nothing else”.

Humour and emojis

The extremism researcher says that part of the rhetoric in the groups alternates between ridicule, dehumanisation and indirect threats. According to Fangen, it also bears the hallmarks of an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mindset.

“In one case, images of bruised and battered white women are displayed. In the discussion below the image, the group members take for granted that Muslim men have harmed the women, but no link is posted confirming this”, she says.

In other cases, individual public figures are referred to in negative terms. These figures might include Muslims who hold positions of political power or representatives from the majority population who hold liberal views on immigration.

“Despite the fact that the rhetoric can be seen as harassment, the seriousness is camouflaged by the widespread use of emojis and a humorous tone. As a result, this can make it rather unclear whether people actually mean what they write”, says Fangen.

Ideas are spread more quickly

The September 11 terrorist attack on the United States in 2001 and later cases of Islamist terror, as well as the refugee crisis and the rise of ISIS in Syria, have contributed to a growing stigmatisation of Muslims and a stronger ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mindset. According to Fangen Islam has to a greater extent also been associated with threats and danger.

Over the past 20 years, social media have also contributed to the development of discussion forums where the use of emojis and emotionally charged discussions reinforce xenophobic attitudes.

The fact that it has become easier to freely express oneself is, according to some theorists, positive. According to Fangen, the so-called pressure cooker hypothesis suggests that people are able to vent their frustrations before it ‘boils over’.

“This hypothesis provides a good description of the anger that many of the participants in the Facebook groups seem to harbour. In a forum, they are able to get support from others who experience things the same way.”

Echo chambers

The researcher explains that other theorists have pointed to the danger of echo chambers. This is where people express their opinions to like-minded people without meeting opposition. After a while, the language used to discuss various objects of hate gradually becomes more intimidating. In such cases, discussion groups can reinforce negative and generalising attitudes toward Muslims, according to Fangen.

“We must accept a broad arena of free speech. It is important in a democracy. However, personal harassment and threats cross a line, which is also regulated by law”.

Therefore, Fangen believes that social media moderators have a huge responsibility. In a project she is currently part of, they also interview individual moderators about what they consider their role to be.

“If a person from outside the group makes counter-arguments, he or she is easily rebuked. However, when a moderator sets a limit on for where the line is crossed, such as racism or harassment being unacceptable, the group members will have to comply with it”, says Fangen.

She explains that research exists on the effect of moderator intervention, but there is still not enough knowledge regarding this field. Moderation that is too strict may cause members to move on to more uncensored sites, such as 4chan, 8chan or Telegram.

A more conservative far right

The Norwegian Progress Party has made it clear that it wants gender equality. However, in certain other European countries, right-wing populist parties are defending more conservative family politics, supporting the idea that women should be housewives.

Fangen elaborates on this in the article ‘Gender and Family Politics on the German Far Right" (co-written with Lisanne Lichtenberg), which will soon be published in the journal Patterns of Prejudice.

“We are now seeing an emerging right-wing populist political trend in certain European countries, arguing that gender equality has gone too far and that more conservative family politics are needed”, she says.

She highlights Poland’s ruling national conservative and right-wing populist party called ‘Law and Justice’ as an example. The party recently tightened regulations regarding Polish abortion legislation.

New prime minister

In the study on the two Norwegian Facebook groups, Fangen has not seen any tendencies in defence of conservative family politics.

“On the contrary, many of the members want a new female prime minister, only one with a more explicit and critical attitude towards immigration compared to the current one. There is also an implicit acceptance of gender equality as a common good we must protect”, she says.

However, some tendencies run counter to such a mindset of equality, she points out. For example, Muslim women are referred to in derogatory terms, and Norwegian, non-Muslim girls are referred to as victims who are unable to look after themselves.

References:

Katrine Fangen et al, Politics, Religion & Ideology. Special Issue on Gender and the Far Right, 2020.

Katrine Fangen and Lisanne Lichtenberg: Gender and family politics on the German Far Right. Patterns of Prejudice. (forthcoming)

——

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no