Troubled waters text for help

Fish and other freshwater organisms can be devastated by runoffs from construction work. Such environmental threats can be curbed by probes that notify mobile phones when something has gone wrong.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Consider a construction project where earthmovers and heavy machinery are in action hours a day. Turf and trees which have held the soil for centuries have been removed. Workers have completed their shifts and vacated the site.

It starts to rain, first gently, but it’s followed by a downpour. Trickles of water running through the construction area merge into streams. The torrent intensifies and the stream shifts course, bypassing ditches and containment ponds that were dug to tackle such run-offs.

The stream continues to swell and triggers a landslide in a newly dug slope. The ooze runs into the nearby river and into a protected lake further down in the valley where salmon are spawning. The sediments continue to flow in for hours if nothing is done.

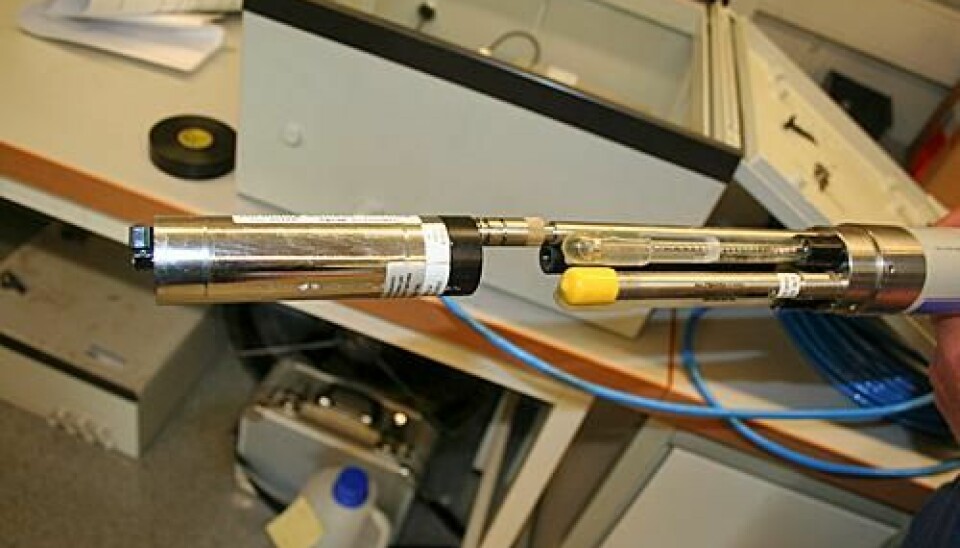

But this river is equipped with a small device – a probe – which continually monitors water conditions streaming past it. It reacts to the change in water quality and broadcasts an alarm in the form of a text message. The message notifies people who can do something to halt the pollution.

Cellphone network

Online monitoring allows for 24/7 control of streams, groundwater and lakes. The results are transmitted via the mobile phone network to online databases.

“This is a tool that's being used more and more in environmental monitoring,” says researcher Roger Roseth, of the Norwegian Institute for Agricultural and Environmental Research (Bioforsk).

Roseth is also responsible for a number of remote-controlled monitoring stations around the southern parts of Norway.

The sensors are based on proven technology. They provide basic data about temperatures, water levels and other factors that can be used to calculate particle content, salts, pH values and chemical pollutants.

The probes are linked to a log unit which supervises the measurements. It stores the data and automatically notifies via mobile phone when predetermined limits are exceeded.

A text message is then sent to alert the management of a construction project, which can rush to the site and find out what’s wrong.

Can happen fast

When new roads, high-voltage power lines or railway tracks are being constructed, the focus is especially on the mudding of nearby streams, rivers and lakes.

“Construction work can be an unpredictable process,” says Roseth.

The pollution problem can crop up suddenly. So it’s no use in sampling for water quality in a nearby stream once a week. If anything were to be found at all, it could be too late to avert the problem.

This is the great advantage of probes that work day and night. They can be transferred from place to place as the construction moves down the line, and can be adapted to specific local needs.

They can be supplemented with a device that automatically samples water, for instance on a daily basis for a week. All the researchers need to do is to fetch the water bottles and bring them back to the lab, Roseth says.

He assures us that he and his colleagues are not afraid of losing their jobs because of automation:

“The technology simply enables us to do our work better.”

Vulnerable river mussels

The Norwegian Public Roads Administration is one of the users of this kind of environmental supervision in its construction projects. Last year a new section of Highway 7 was opened up in Ringerike Municipality, between two towns in East Norway.

Planners were particularly concerned about a jeopardised species of freshwater mussels. The road had to cut a new swath along the north bank of the Sogna River.

Sogna contains one of the Norwegian stocks of a river mussel, a rare and threatened species which Norway is responsible for protecting through international agreements.

The new route would cut right through ridges and valleys that slope down to the river. This ravine landscape is composed of clays, so siltation of the river was a real threat.

County environmental authorities warned against the risk this posed for river life and called for a monitoring programme. Highway authorities were also alert and concerned about the risk.

Monitored before and after

“In the planning stage we were worried about the danger of polluting Sogna,” says Project Manager Tore Gomo of the Norwegian Public Roads Administration.

The first step involved various initiatives to prevent run-offs during the construction work. These were carried out in collaboration with the road construction contractor. Bioforsk also placed two probes in the Sogna to gauge conditions in the river prior to the roadwork.

Gomo explains that this was to ensure that nothing abnormal occurred later on. It was likewise an opportunity to set the standards so they wouldn’t be blamed for changes that hadn’t occurred.

Using measurements before, during and after construction work, they could document whether the river had been impacted.

To date, it seems that life is normal for the river mussels in this part of the Sogna. These molluscs grow very slowly, however, so it’s still too early to summarise the results.

“We’ve received some notifications of heavy muddying. But it will take several years before we know what the final results were,” says Åsmund Tysse, a consultant at the environmental department of the County Governor at Buskerud.

He praises the road authorities for their efforts in connection with construction work.

The Romerike Tunnel

In the 1990s the Romerike Tunnel, a railway tunnel between Oslo and Lillestrøm, became a textbook example of how badly things can go during major transportation construction developments.

The water in several lakes and ponds in a forest on the east side of Oslo drained completely because of leaks through underlying rock strata to the tunnel hundreds of metres below. To make matters worse, toxins from the industrial sealant Rhoca Gill used on the tunnel walls leaked out.

The Romerike Tunnel was opened in 1999 as part of the high-speed train line to Oslo’s main airport, Gardermoen.

“The Gardermoen Line inspired developers, particularly the Norwegian National Rail Administration, to start investigating groundwater in connection with tunnel construction and operations,” says Bioforsk's Sigurd Roseth.

Bioforsk is monitoring groundwater in connection with a new tunnel, for the double track being built between Oslo and the town of Ski in Akershus County.

The probes used there are programmed to send an alert when the water table drops.

Tunnel work often represents a bigger environmental risk than other construction because of the use of potential chemical pollutants in addition to the displacement of soil and rock particles.

Tunnels usually have their own purification facilities for water used or impacted by the construction machinery, and probes come in handy to monitor the efficiency of such cleansing technology.

New opportunities

The Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA) is another agency that supervises freshwater in connection with larger construction projects.

In Oslo, NIVA is involved in monitoring the Akerselva river in connection with a major municipal sewage project. At Minnesund in Akershus County, the quality of water in Lake Mjøsa is being monitored, as a new railway and a E-6 Highway route are being constructed.

“The technology offers a host of new opportunities. Now it’s easier for us to obtain real-time solutions,” says Research Manager John Rune Selvik at NIVA.

Selvik shares Roseth's impression that environmental authorities are now more prone to demand environmental monitoring. The same can be said for private and public builders who have grown more concerned about keeping a close watch for potential effluents and discharges from their projects.

He says there’s been an awareness of the problem for a long time but this awareness has really started to increase recently – at least among major players like the Norwegian Public Roads Administration.

In addition to Bioforsk and NIVA, several consultancies carry out such environmental monitoring.

---------------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling