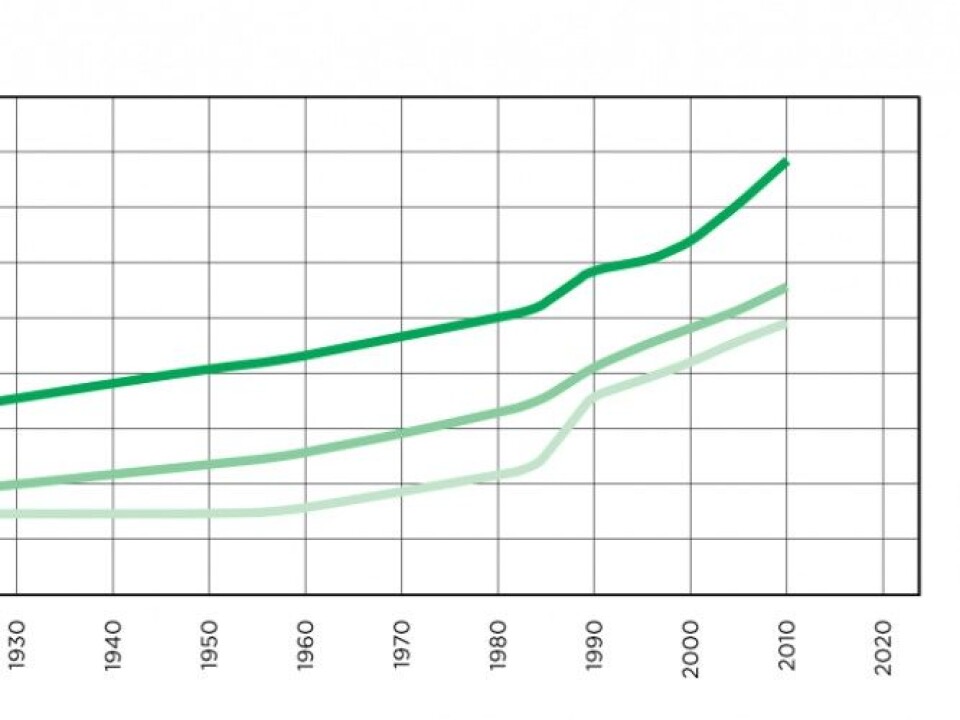

Norwegian woods triple since WW2

Norway now has three times as much forest as it did before World War Two. The volume of growth this year will be the equivalent of nearly 100 sacks of firewood per Norwegian.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

In 1925 the volume of Norway’s forests was 300 million cubic meters of wood.

Today it adds up to 900 million cubic meters.

This year that biomass increased by another 15 million cubic meters. This equates to nearly 100 sacks of firewood for every one of Norway’s five million inhabitants.

Soaring in the graphs

The main reason why the forest has grown so much in the past decades is clear. In the 1960s nearly 100 million Norway spruce trees were planted annually. There was a reforestation campaign going and much of that was done by school children. These trees are now reaching maturity and are in a development phase with plenty of growth.

But the forests are growing much faster than can be explained by seeding and seedling-planting projects by schools and foresters.

Researchers at the Norwegian Forest and Landscape Institute in Ås, a half-hour’s train ride southeast of Oslo, have models and tables showing how the forest actually should have grown. But spruce, pines and birches are not adhering to these trajectories and growing as expected. They are all growing faster.

Forestry experts are not certain why.

What’s the cause?

Like detectives, the researchers have their list of usual suspects: Higher average temperatures, longer growth seasons, more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and more nitrogen deposition from the air. Some also point to a decrease of grazing by domesticated and wild animals in the forest.

“The answer is probably a combination of these factors. What we can’t answer is the relative contribution of these individual factors and the interplay among them,” says Rasmus Astrup at the institute in Ås.

“We are now conducting a lot of research on this. But providing a good answer is far from easy.”

Not surprisingly, Astrup and his colleagues think our warming climate has a major role. In a cold country like Norway, temperature is a strong factor with regard to growth.

Fear of dying forests

Just a few decades ago, scientists were issuing warnings about a prospective death of forests.

Mounting acid precipitation was the culprit of that scenario. There were also fears that the wood products industry was taking an unsustainably big bite.

This fear was not ungrounded. In 1916 the forest ranger Agnar Barth wrote an article in the forestry journal Tidsskrift for skogbruket. The headline was: “Norway’s forests making huge strides towards oblivion”.

Barth stated: “All the forestry experts in our country have long since ascertained that forest growth is nowhere close to compensating for the annual felling of trees.”

Up until the 1950s this was true, and loggers were actually chopping trees down as fast as ― if not faster ― than the forests could replenish the biomass.

What followed then was more modern and effective forestry.

Paradoxically, since those days the forestry industry has not been able to cut more than half this growth in the forest.

Researcher Rasmus Astrup says that now and in the next decades the forest that was planted from 1950 to 1970 is becoming commercially mature. This is explains much of why the forest is growing so prolifically now and will continue to do so a few decades.

Gaining 15 million m3

The annual growth of Norwegian forests (25 million m3), minus annual cutting (10 million m3), gives the net growth of Norwegian forests of about 15 m3 of wood per year.

When we write that this is the equivalent of nearly 100 sacks of wood per Norwegian, we are calculating with the standard 40-litre sacks or nets of firewood for sale which contain about 25 to 30 percent air.

Monitoring the forest

Norway’s forests have been meticulously monitored since the 1920s by the Land Resource Surveys.

The volume of the forest can be divided into three groups of trees: Spruce (44 percent), pine (31 percent), deciduous [leafy] trees (25 percent). Current development is heading toward fewer spruce and more deciduous trees.

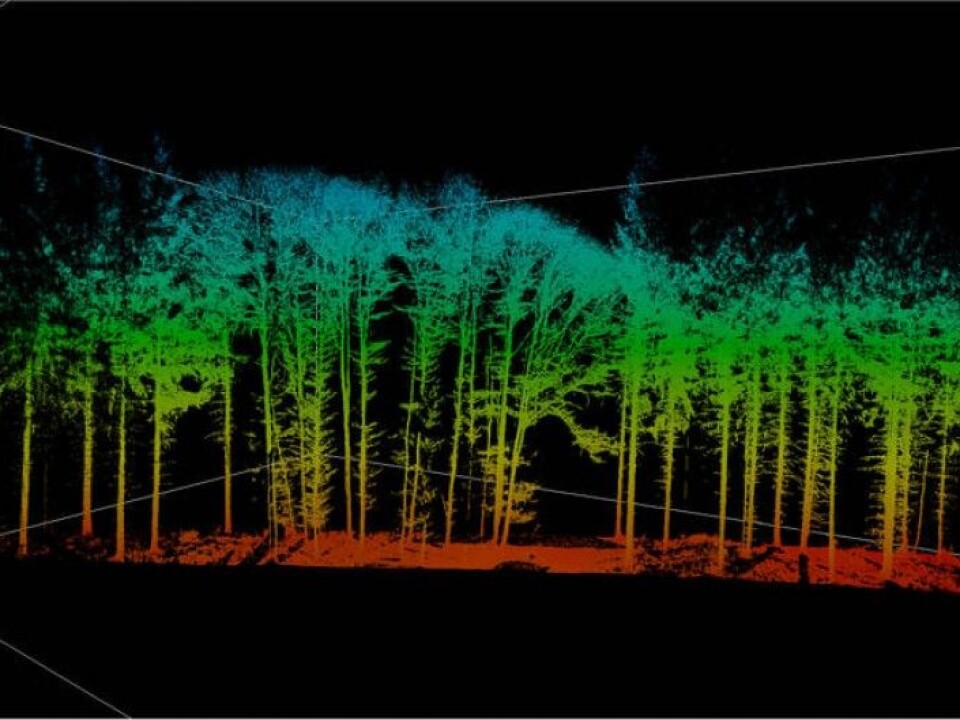

Of course the forest researchers are not measuring every tree in the forest.

What they do is to keep track of 22,000 stands of trees, each of which covers 250 square meters of forest floor, about as much as the floor space in a large house. These have been placed in representative spots all over the country and each are visited at five-year intervals.

German forests gaining too

Researchers in Germany have kept tabs on 600,000 trees for over 140 years.

European beech trees now grow 77 percent faster than they did in 1960. Norway spruces down on the Continent grow 32 percent faster, according to researchers at Technische Universität München (TUM).

The German scientists have found that trees are growing through their various stages in the same way as before, but just a whole lot faster.

However, when scientists try to “see the forests for the trees”, they find that the woods are not expanding at the same rate as the individual trees.

This is because each tree now takes up more space. German scientists say that compared to 1960 there are now 20 percent fewer trees in the Central European forests. But total volume of biomass has increased.

Despite these gains, the Central European forest has not put on volume nearly as much as Norwegian woods.

When scientists at TUM are asked for reasons why the forests are gaining mass, they stress first that the growth season has become longer because of the warmer and wetter climate. But these scientists in Munich add that increased concentrations of carbon dioxide and more nitrogen deposition from the air are also contributing factors.

----------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling