Public helps scientists scout species

Public involvement in recording observations is growing increasingly popular round the world. Members of the general public in Norway have to date made an impressive 10.7 million registrations.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Volunteers up and down the length of Norway post 5,000 fresh nature observations per day on the website artsobservasjoner.no. There are currently 8,500 people who help keep tabs on the country’s wealth of plant and animal species.

This enormous amount of data on Norwegian nature is used by government officials as well as researchers.

Third largest in the world

Thanks to artsobservasjoner.no little Norway has become the third most active country in the world with this type of data on biodiversity, out-performed only by Sweden’s Artportalen and the American eBird.

Norwegian nature enthusiasts have thus become part of the international phenomenon known as citizen science.

Ivar Myklebust, the director of the Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre (Artsdatabanken), says such public involvement in recording observations is growing increasingly popular round the world.

“This is becoming more common and better recognised globally, especially in astronomy and biology.”

Quality control in reverse

Nils Valland, a senior advisor at Artsdatabanken says the Norwegian and Swedish species databases are special because all observations are made accessible immediately on the internet.

This is contrary to traditional ways of collecting scientific data, where observations are assiduously quality-controlled prior to publication. The Swedish and Norwegian version used by these websites involves implementing quality control afterwards.

Many are involved in that process too. As soon as a picture or an observation is registered on the website, it can be commented by anyone who has logged on.

Artsdatabanken views the scheme as a recipe for success in helping amateur information find the quickest path to those who have use for the knowledge.

Sources of knowledge which used to be hard to tap, or entirely closed, are now open to anyone who is interested.

Nils Valland says that many of those who report their observations have higher educations. They are often teachers or bureaucrats in the public sector. But many of these observers have no formal education in biology. They are self-taught or they might have some link to professional circles where practical instruction is given in determining species.

“They are called amateurs, but when it comes to some categories such as birds, they can be fully on a par with ornithologists in identifying species,” reveals Valland.

Justice

All reports to artsobservasjoner.no are made openly by full name. These contributors own the right to their own observations.

Nils Valland thinks the quality of this data is generally good. In addition to the efficient sort of self-justice represented by commentators on the web, a number of professional experts from biology organisations ensure quality controls of findings of red-listed species.

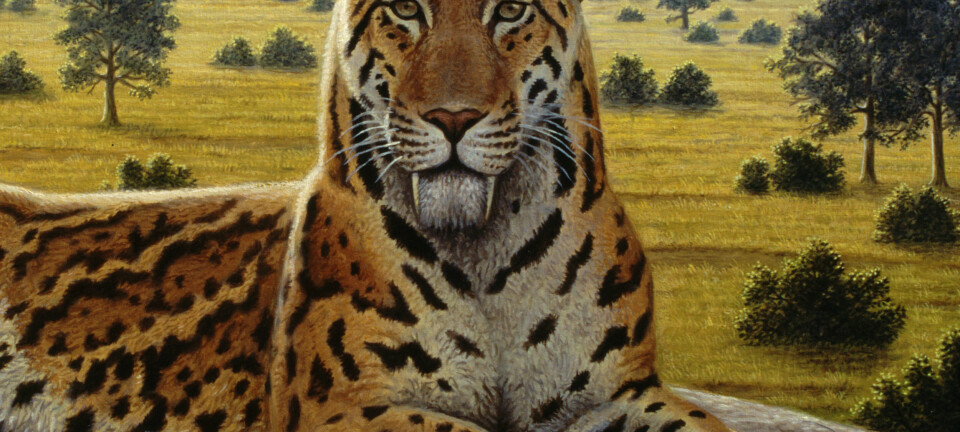

Norway currently has 4,500 species that are red-listed. About 2,500 are considered to be severely in danger of extinction.

Artsobservasjoner.no is run by Artsdatabanken in collaboration with an umbrella organisation called the Norwegian Biodiversity Network (SABIMA).

------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling