OECD director: Norway can do better

More people are struggling financially in Norway. In many other European countries, the trend is similar. But for one group, the development is more dramatic in Norway than in other countries.

A total of 151,000 people in Norway are now in the 'in dire straits' category, according to figures from the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration NAV. This group has become three times larger than before the pandemic.

Just over one in five has sought financial help from NAV.

17 per cent of these have visited places that distribute free food.

Large numbers

“These are large numbers,” Labour and Welfare Director Hans Christian Holte said when he opened the NAV conference last week.

NAV has collected new figures from the country's 12 largest municipalities. These show that the number of social assistance recipients has increased by 16 per cent in the last year.

Among the new recipients, most are Ukrainian refugees. But more families with children and young people are also receiving social assistance.

In another report presented at the NAV conference, researchers from the Fafo Institute for Labour and Social Research show that more groups in society need assistance from food banks.

Over half of those who receive free food from food banks have children.

Researchers believe that a new type of poverty is emerging in Norway. You can read about it here.

Something has changed

Most viewed

No content

In the mid-1980s, the greatest risk of poverty in Norway was for people over the age of 75.

This has now changed dramatically.

In 2021, figures showed that the risk of poverty in the youngest age group in Norway, those between 18 and 25 years, has increased significantly.

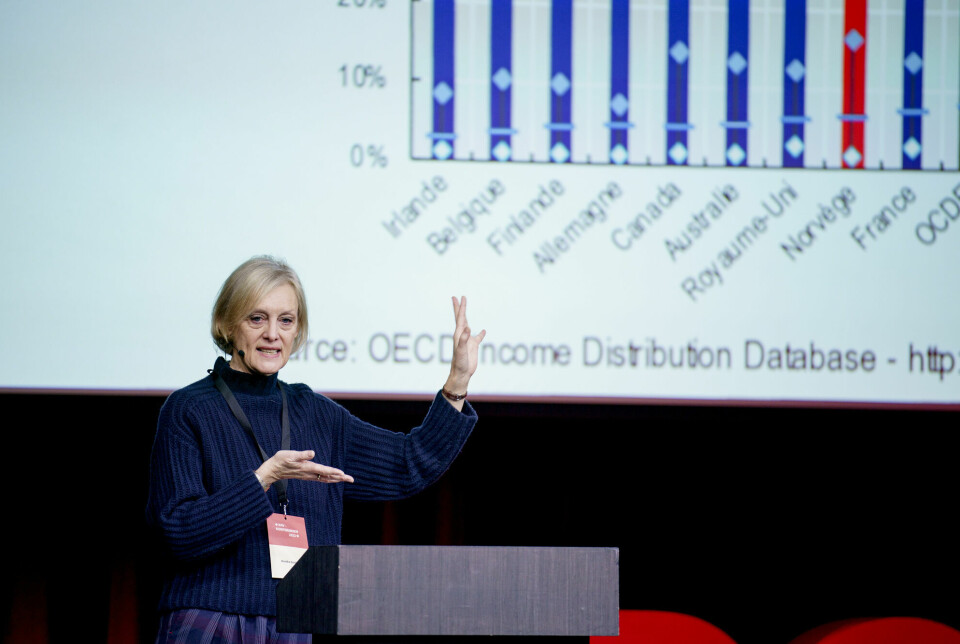

This was reported by Monika Queisser, head of the social policy department at the OECD, at the conference.

“This has happened throughout the OECD,” she reported. “But the development is much more dramatic in Norway than in other countries.”

What happens with an increasingly elderly population?

The greatest success in Norwegian social policy over the last 40 years has been the significant reduction of poverty among the oldest in society.

This is probably due to a combination of a good pension policy and the fact that more women are working in Norway, Queisser believes.

But in the years ahead, there will be many more older people. Major demographic changes are happening in the population.

“How will you continue this great success and still have good pensions, without placing too much of a burden on the young?” the OECD director asks.

Can eliminate poverty entirely

Getting more people into work is perhaps the most important way to reduce poverty, Queisser asserts.

Figures show that if no one in a household works, the risk poverty is much higher. It is also higher if only one person in a multi-person household works. If two people in the household work, the risk disappears almost completely.

Ensuring that two adults in each household are employed, a step that benefits both gender equality and integration, is crucial for poverty prevention, Queisser said.

Norway is still doing well

Despite more people struggling financially, Norway ranks well among both EU countries and OECD countries in terms of poverty.

In Norway, barely 6.7 per cent of the population lived on less than half of the median income in the country in 2021. The median income is the income that lies in the middle of the scale of all incomes in a country.

In 2021, the amount was NOK 18,700 (1,710 USD) a month.

The OECD uses this as a measure of relative poverty, meaning poverty in relation to the majority of the population in a country.

Can do better

“Norway is doing well compared to other countries. But you can do better,” Queisser said.

The average of the population in the EU living in poverty in 2021 was 10.7 per cent. In OECD countries, the average was 11.6 per cent.

Six other countries are doing better than Norway. Iceland has the fewest poor people, with 5 per cent.

The Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France also have fewer poor than Norway.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no