Volcanoes in Norway: Oslo was an inferno 300 million years ago

Researchers see traces of dramatic volcanic eruptions in Norway.

There’s unrest beneath the surface on the Reykjanes Peninsula in Iceland, and residents have prepared for a possible new volcanic eruption.

Norway doesn’t have to fear volcanic eruptions that could hit cities. But researchers do find traces of violent forces when they look into the country's geological history.

In Norway's capital Oslo, there were supervolcanoes that covered large areas with ash and lava. In the sea off Norway, there was volcanism that may be responsible for an extreme climate change in the past.

“Norway is also a volcanic country. It's just that the vast majority of volcanoes are below sea level,” Reidar Müller says.

In his new book, Norge. Landet vårt gjennom tre milliarder år (Norway. Our country over three billion years), Müller writes about events that have shaped our landscape, told through 60 locations in Norway.

He tells the reader about the remnants of a huge desert in Brumunddal, about Norway's oldest traces of life in Alta, and about discoveries of mammoth teeth in Gudbrandsdalen.

In the book, Müller also writes about volcanoes. Volcanism has left its mark on the country, and it is still going on today – underwater.

Volcanoes under water

The northern part of the underground mountain range of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is found in the sea between Norway and Greenland.

This is where the tectonic plate carrying Europe is drifting away from North America.

“The flight between Oslo and New York gets two centimetres longer every year,” geologist and author Müller says.

Part of the Mid-Atlantic ridge lies within Norwegian territory. Active volcanism is taking place here, Müller explains.

On average, there is one volcanic eruption in Norwegian deep-sea areas every year, and a new seabed is then formed, according to a previous sciencenorway.no article.

West of Jan Mayen, there are submarine volcanoes just a few dozen metres below the surface of the sea. New land could actually be forming here.

The next eruption there could possibly create a new Norwegian island in the Atlantic Ocean.

Norway's only active volcano

Jan Mayen is where Norway's only active volcano on land is located. Beerenberg is almost 2,300 metres high and the volcano has a diameter of approximately 20 kilometres.

Researchers thought Beerenberg was dead until a surprise eruption in 1970.

Lava flowed out on the northeast side. The volcanic eruption made the island four square kilometres larger. Some of it was later eroded away by the sea, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia (link in Norwegian). The volcano erupted again in 1985.

Two further areas on Spitsbergen in Svalbard have hot springs: Jotunkildene and Trollkildene.

They have probably been there since a nearby volcano was active between 100,000 and 250,000 years ago.

Warm water on the seabed

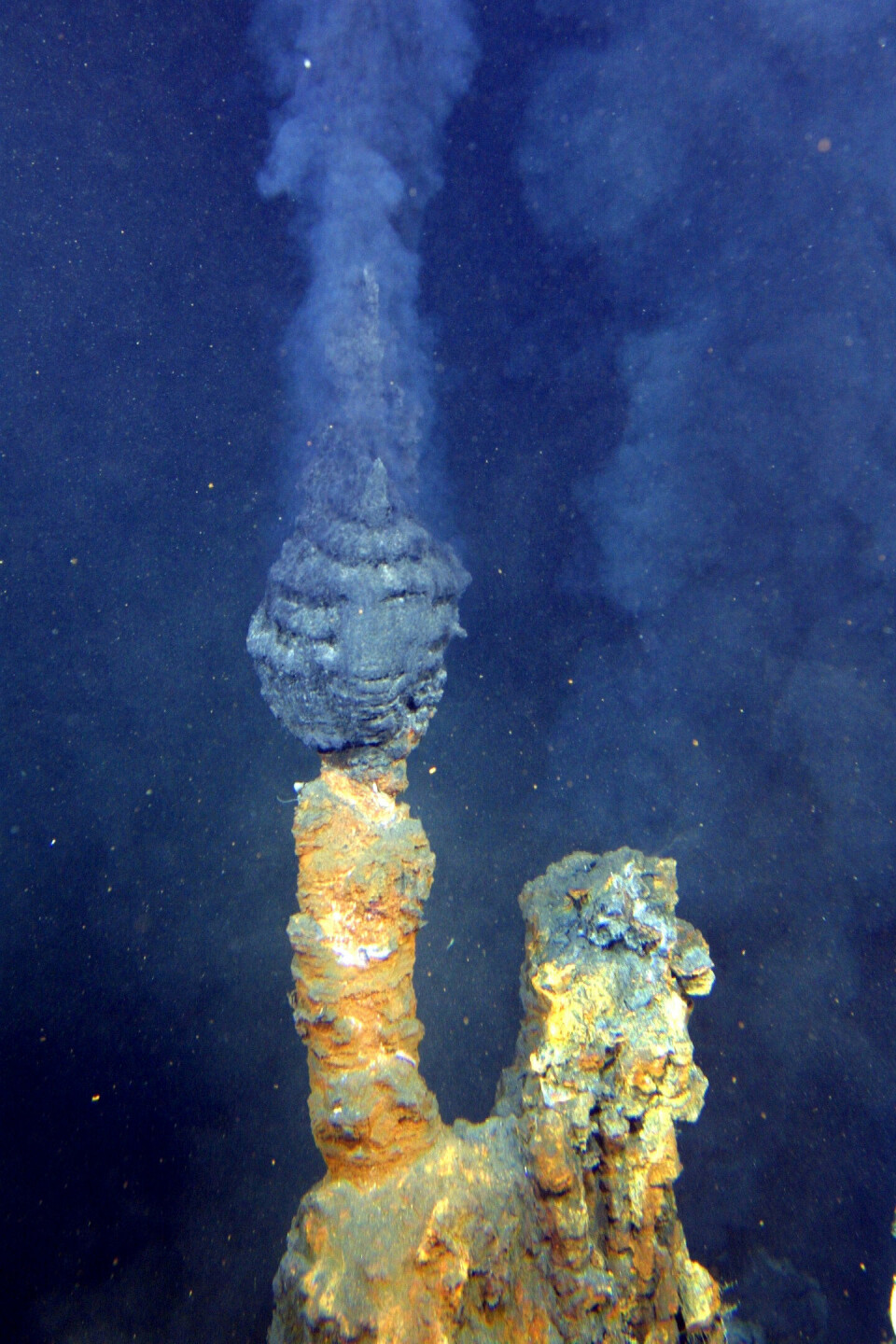

Along the mid-ocean ridge in the Norwegian area, there are also what are known as hydrothermal vents.

In volcanic areas, where it's warm under the seabed, water is drawn down into the crust in some places. The water dissolves metals and comes back out of chimney-like structures on the seabed, looking like black smoke.

Metal-rich deposits are formed in these areas. There is also a very special kind of life found here. You can read more about it here.

There is now a discussion about whether Norway should open up for mineral extraction on the seabed, including at hydrothermal vents that are no longer active.

The metals in several of the mines found on land in Norway also come from hot springs on the seabed, Müller explains. They originate from a sea that no longer exists.

Metals from an ancient sea

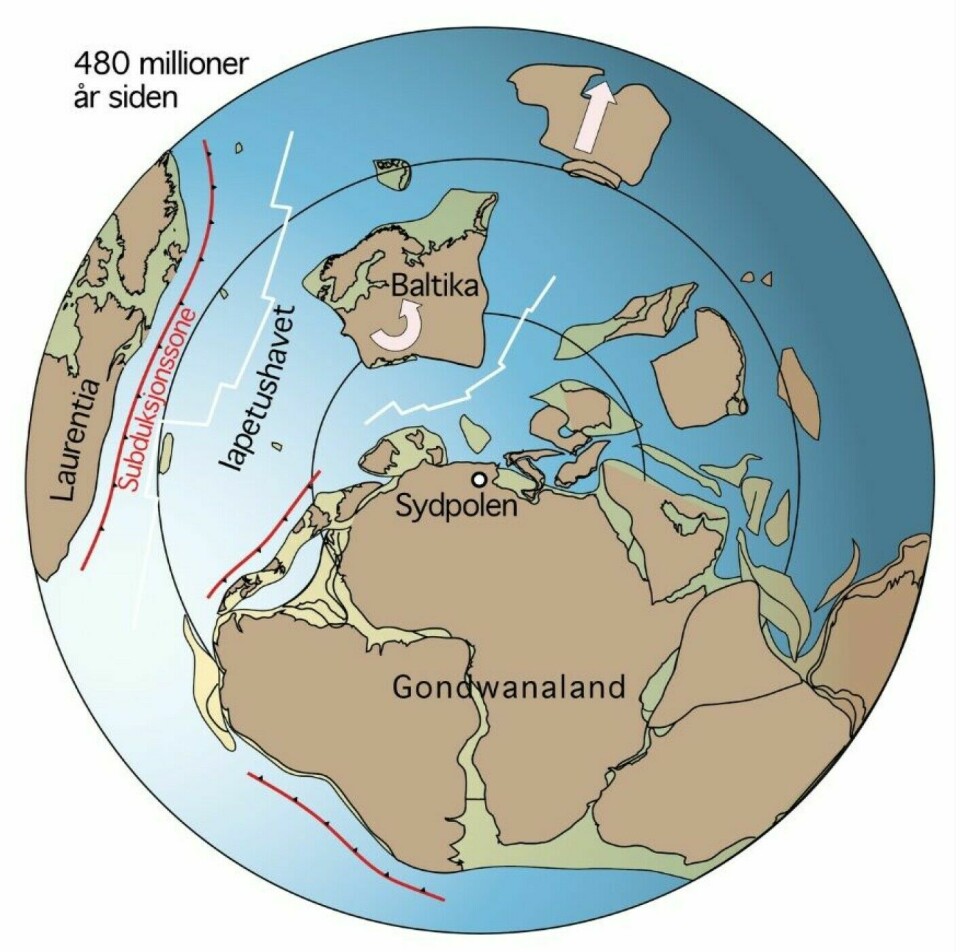

“Some 490 million years ago, we could have travelled across an ocean that once lay where the Atlantic Ocean is today. It was called the Iapetus Ocean,” Müller says.

The Iapetus Ocean opened between the tectonic plates of North America and Norway.

Volcanism occurred here just like today. Hot springs on the seabed pumped out warm water and formed metal-rich mineral deposits.

“The metals extracted at Røros, Folldal, and Løkken originated from these underwater hot springs. Many of the mining communities are founded on 470 million-year-old volcanism in a sea that no longer exists,” Müller says.

How did these metal deposits end up on land?

The North American and Norwegian plates were on a collision course, causing the Iapetus Ocean to close again.

“When that happened, the old volcanic seabed crust was pushed in across Norway,” he says.

Climate shock in the past

The North Atlantic that lies between Norway and Greenland today also has a similar origin.

“Norway and Greenland began to drift apart around 55 million years ago. At that time, the shortest distance between Norway and Greenland was only 150 kilometres. Today, it’s 1,600 kilometres,” Müller says.

As the plates drifted apart, a new sea opened in the middle. This led to widespread volcanic activity off the coast of Norway.

Underwater volcanism has been blamed for one of the great global climate changes of the past. About 56 million years ago, temperatures rose by five to eight degrees in an already warm world. This global warming period is called the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM).

“Large quantities of greenhouse gases are believed to have been released in connection with the volcanism,” says Müller. “On the Norwegian continental shelf, we find layers of ash and volcanic tunnels that have penetrated the crust. There are dramatic traces of this activity in Norway."

Oslo was hellish

Oslo also bearstraces of intense volcanism.

"Oslo was a hellish place 300 million years ago – a volcanic inferno with fire-spewing fissured in the Earth's crust," Müller writes in his book.

“There was violent volcanic activity in the Oslo area between 310 and 240 million years ago over a period of 70 million years. There were large fissure volcano systems in Oslo, similar to what exists in Iceland today,” Müller tells sciencenorway.no.

A Norwegian forskning.no article describes the ancient magma passages that wind through the bedrock in Oslo and surrounding regions.

One of the fissures runs right through Frogner Park, says Müller. You can see it if you stand by the Monolith.

“There’s a wooded ridge that goes up towards the Monolith. It continues up towards Vindern and into an open field. Hundreds of such cracks exist in the Oslo area," he says.

What you’re seeing are ancient magma channels that were originally deep in the Earth's crust. Over time, a couple of kilometres of stone that lay above have been worn away, allowing the channels of solidified magma to come to the surface.

Oslofjord could have become a sea

Most volcanoes occur where tectonic plates meet. No such plate boundary exists under Norway, so why were there volcanoes in Oslo for 70 million years?

“It was almost as if Norway was about to be split in two,” says Müller.

“There was movement between today’s Vestfold and Østfold. The Earth's crust had thinned, cracked open, and formed a rift where magma could seep up through the cracks in the crust.”

The crust was stretched and became thinner. If this trend had continued, a new sea could have developed where the Oslofjord is today, Müller explains. But the development stopped.

It began with fissure volcanoes, but eventually, large central volcanoes developed. These are volcanoes that have multiple eruptions in the same area.

Some of them exploded, and the explosions were big enough to be called supervolcanoes, according to Müller. There were 15-20 large volcanoes around Oslo, including the Hurdal Volcano and Bærum Volcano. The largest was probably the Øyangen Volcano.

The volcanic period has left its mark on the landscape today.

“Volcanic rocks are hard. They’re a bit like the knots in a worn floor – they stand out a bit in the landscape,” he says.

All around Oslo we can find knolls and plateaus with durable volcanic rocks that protrude. They were once formed in passages and chambers of underground magma.

No risk of volcanic eruption

Other areas in Norway also have traces of ancient volcanism, including the Fen Complex in Telemark.

Rocks here originate from a volcano that was active 580 million years ago. The lava was of a rare type containing carbonatite.

The volcanic mountain has been worn away, making the supply pipe to the volcano accessible for study, Müller writes in the book.

The Fen Complex has deposits of some rare earth metals and thorium, which might be interesting to extract in the future.

Is there a chance of a volcanic eruption in Norway now?

“No, there's no risk of that,” says Müller. “Not on the mainland anyway.”

However, it's not impossible that there could be a minor earthquake in Oslo, rooted in the old rift. But it won't be a disaster scenario like in the 2018 movie The Quake.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no