Who pooped – 250 million years ago?

Researchers on Svalbard found thousands of poo-shaped lumps in the mountains. Were they really faeces? And if so, could they show us what the prehistoric animals had eaten?

Vanja Simonsen pulls out a drawer at the Natural History Museum in Oslo.

It contains boxes upon boxes of small stones. At first glance, they resemble gravel and small pebbles.

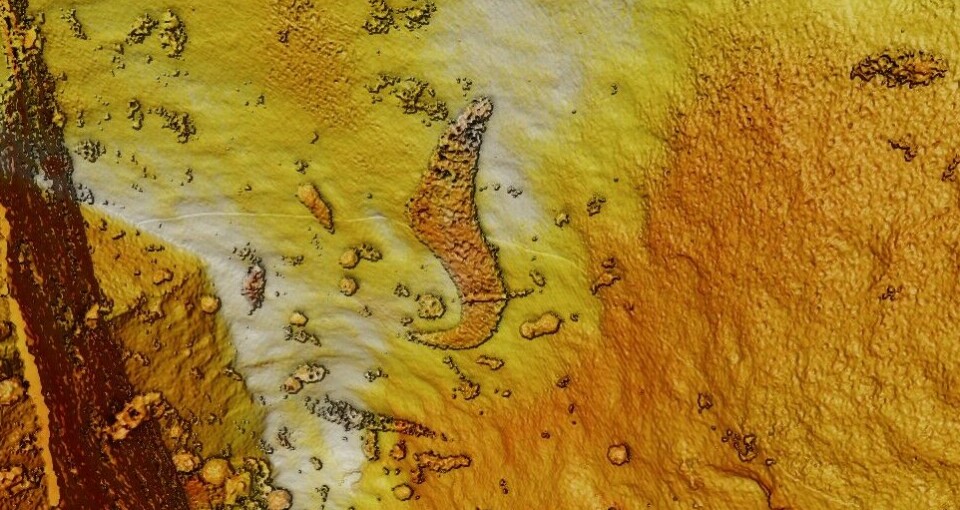

But the stones are actually a kind of bycatch, collected as part of the excavations on Marmierfjellet on Svalbard in 2015 and 2016.

The researchers primarily focused on skeletons of marine animals, such as ichthyosaurs, fish, sharks, and archosaurs.

However, some of the stones that appeared in the same excavating layers were a bit too intriguing to leave behind.

Coprolites

The stones are small and dark, with smooth, almost polished surfaces. Some are just fragments, like curved flakes or round discs. But others are whole, oblong sausage shapes that taper at the ends.

Anyone can see that they resemble droppings.

But are they really?

Most viewed

“We were a little unsure at first if they could be phosphate nodules. But then we loaded a few of them into the CT scanner. That's when we saw that these are definitely coprolites – fossilised poop,” says Simonsen.

The stones were full of bone fragments.

They turned out to reveal entirely new details about prehistoric life on Svalbard.

Remains of new animals found

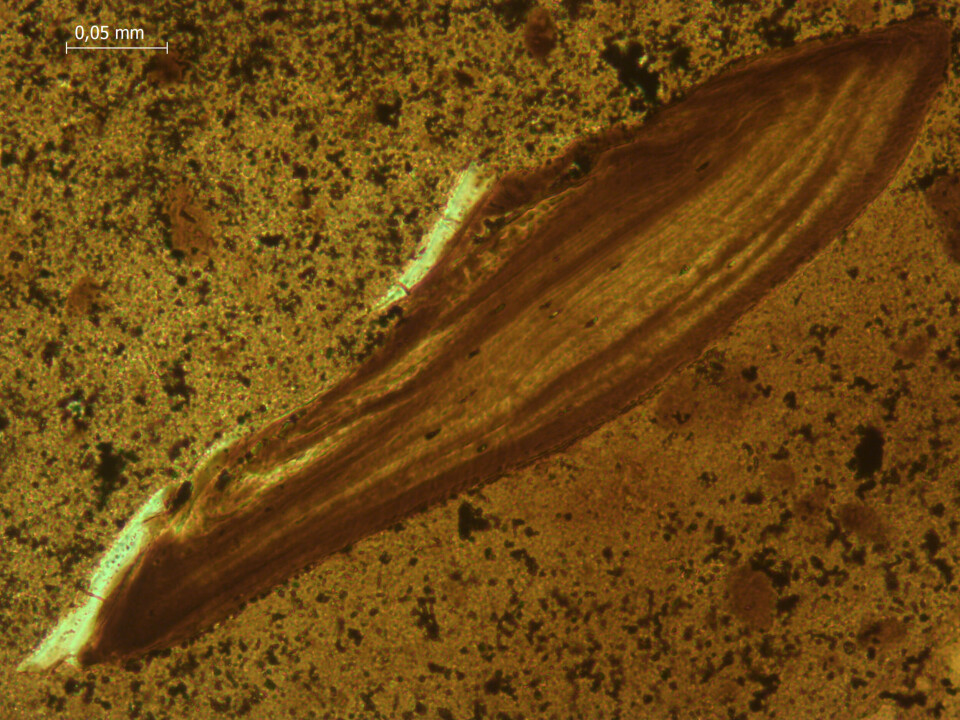

Simonsen carried out her master's specifically on these coprolites. She selected 26 coprolites to run through the CT scanner at the Natural History Museum. The images enabled her to identify some of the bone fragments in the fossilised faeces.

“I found bone remains from ichthyosaurs and fish. Whole fish scales and a shark tooth also showed up,” she says.

But perhaps even more exciting was the discovery of shells and tentacle hooks from molluscs and needle-like spicules from sea sponges.

No other such mollusc finds have been made in this excavation layer on Svalbard.

“They’ve only been preserved in the coprolites,” says Simonsen.

The faeces are truly small time capsules that contain previously unknown information.

Poop preserves

The molluscs that lived 250 million years ago were small and decomposed easily, says Simonsen.

The tiny, hard parts of the animals, like squid hooks and sponge spicules, were likely quickly scattered and destroyed.

But inside the faeces, they were more protected. Some of the faeces sank quickly and were buried in the clay seafloor that was there at the time. The conditions there were good for preservation.

“Chemical processes also occur in such faeces that make it more likely to become fossilised and preserved,” says Simonsen.

Who pooped?

The material from the drawer at the museum shows that some creatures ate fish, sharks, ichthyosaurs, and molluscs 250 million years ago.

The question is who that might have been.

“That’s been one of my tasks – trying to figure out who pooped,” says Simonsen. “It’s been a big puzzle.”

She explains that the entire project started with going through large amounts of coprolites and sorting them by shape. The shapes can give an indication of who once produced the droppings.

“There are certain characteristics you can look for,” she says.

For example, previous research has determined that coprolites from sharks are spiral-shaped at one end. We also know that modern crocodiles can have deep grooves and ridges in their faeces.

These external features can be combined with the contents revealed in CT images. It makes sense that ichthyosaurs would eat molluscs, for example.

Images reveal eating habits

The images from the CT scanner and the thin, polished slices of the coprolites showed that the faeces were at least as different on the inside as on the outside.

Some were full of rather large bone fragments, while others contained almost no bones at all. This tells us something about the animal that pooped – not just what they ate, but how.

“The coprolites that we believe originate from ichthyosaurs have rather large and whole bone fragments,” says Simonsen.

This could indicate that the icthyosaurs swallowed large chunks of their prey.

Different digestion

Many sharp bone fragments indicate a digestive system where food passes through quickly.

“Coprolites from fish, for example, are packed with bone remains,” says Simonsen.

When the poop contains fewer and more rounded pieces, the digestive system is likely better at breaking down and utilising the nutrients in the food. In some cases, there is almost no bone left, which may indicate an animal with a very efficient digestive system.

“This is what we see in living crocodiles, for example. They digest bones and everything, and you find almost nothing intact in what they excrete,” she says.

Writing an article

Simonsen is now working on a scientific article about her findings in the Svalbard coprolites, together with supervisors Aubrey Roberts and Jørn Hurum at the Natural History Museum. Hurum led the expeditions on Svalbard and initiated the study to examine the faeces-like stones more closely. But even he is surprised by how much Simonsen has discovered.

“In order to find anything, first of all there has to be something there, and secondly, you need to have good X-ray contrast between the bone and rest of the poop,” says Hurum.

It turned out that both were present in this case.

“We hadn’t done any systematic studies on coprolites before. And then we bring on a student who manages to find a whole world in there!” says Hurum.

He believes the researchers have only had a mere glimpse into a hitherto unexplored goldmine of information about the past.

“There are very few people in the world doing research on this, but I think this field could become huge. And that’s pretty cool,” says the professor.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.