A long-forgotten fossil from 1952 has now been identified as belonging to a prehistoric sea monster

The skeleton belonged to a long-necked sea monster from the dinosaur era.

In 1952, Danish geologist Johannes Troelsen went on an expedition. He was tasked with mapping the geology of the desolate and icy landscape on Ellesmere Island in Canada.

In all his reporting, he briefly mentioned having found some large fossil bones. But not much more was done with them.

Troelsen was not actively searching for fossils.

“He wasn’t out looking for them, and it wasn’t his expertise,” says Lene Liebe Delsett. She is a researcher at the Norwegian Center for Paleontology at the Natural History Museum in Oslo.

From the field diary, it can be seen that geologist Johannes Troelsen walked alone over quite long distances on the vast island while mapping the geology, Delsett explains.

She describes Ellesmere Island as very sparsely populated, cold, and inhospitable.

"We don't know the exact point where he found the fossil, but he wrote down how far it was from a weather station," she says.

Retrieved and stored away again

Delsett and her colleagues have tried to trace the history of the fossil further.

The bones were sent to the Natural History Museum Denmark in Copenhagen, where they remained. They were stored in various boxes and crates, forgotten, and damaged by water leakage.

"They were partially prepared at one point. Some of the bones were sorted and labelled," says Delsett.

But the work was never completed. Not until now.

Together with colleagues from the UK, she has examined the skeleton found over 70 years ago. They can now share the story of what was discovered and what happened to the bones.

Exciting to open the old boxes

The fossils belonged to a very large animal, so the skeleton was divided into several boxes stored in different locations at the museum. It has been a puzzle, says Delsett.

In 2011, the unthinkable happened: The museum was hit by a flood.

"Things were moved quickly. Some water damage occurred, and some fossils lost their labels," she says.

Delsett recounts it was exciting to open the old boxes.

"There's always the risk of disappointment. But we weren't in this case," she says.

Some boxes had not been opened since the 1960s. When they opened them, the researchers could confirm that the discovery was special. They found large, fossilised bones from both the arms and legs.

"That's quite rare," says Delsett.

The bones belonged to an apex predator

The bones have now been described, and the results published in a scientific journal. Researchers have also gained more insight into the vast areas where this large predator lived.

The bones belong to a plesiosaur that lived in the Early Cretaceous period, about 140 million years ago.

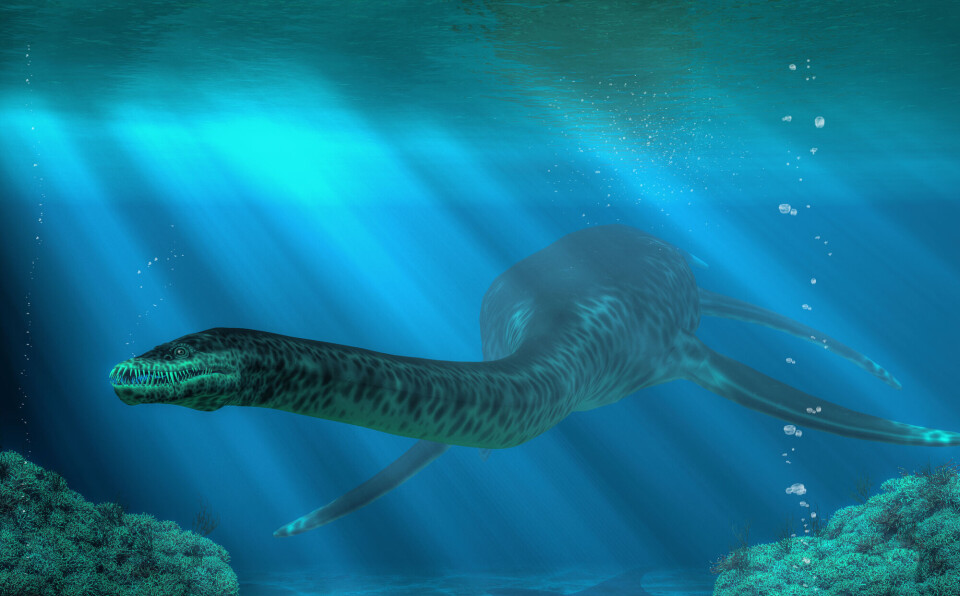

Plesiosaurs were large, long-necked reptiles that lived in the sea. They somewhat resembled depictions of the Loch Ness Monster, according to Delsett.

It was previously known that the bones belonged to a plesiosaur. More precisely, Delsett and her colleagues have determined that it belongs to the genus Colymbosaurus.

The plesiosaur was likely just over three metres long. It had a long neck.

"They have a very special shape that isn't found in any other animals," says Delsett.

Same type has been found in Svalbard and the UK

The arms and legs are about the same size. Researchers are still debating how they actually swam with their strange shape and why they have such long necks.

“Some think the long neck was an adaptation to sneak its head into a school of fish, for example,” says Delsett. She is not entirely convinced.

Researchers believe plesiosaurs had relatively high body temperatures, similar to dinosaurs, she explains. This fits well with their discovery far north, where it was colder in the past as well.

“The interesting thing is that this genus has been found in both Svalbard and the UK. This means the same group existed over a larger area than previously thought," she says.

This is not the only discovery they have made.

Large predators existed in the ecosystem

One of the researchers involved in the study is Simon Schneider, a palaeontologist from the UK. Schneider became aware of the fossil discovery when he read reports from people who have conducted fieldwork on Ellesmere Island.

Schneider has researched clams and the dinosaur-era ecosystem in what is now the Canadian Arctic.

“One question they’ve pondered is whether the ecosystem was rich or poor and how it functioned,” says Lene Liebe Delsett.

Researchers have also discussed how the different marine areas in the Arctic were connected at the time.

In the Sverdrup Basin, where Ellesmere Island is located today, very few fossils from the period around 140 million years ago have been found. Only small invertebrates like clams have been discovered.

The plesiosaur shows that large predators existed there too.

Important to preserve collections

There are probably many treasures in other natural history museums that have not yet been described due to a lack of time and funding, Delsett says.

Aubrey Jane Roberts is a university lecturer at the Natural History Museum in Oslo and an expert on plesiosaurs.

She has not participated in the new study but has read it. She says the study is an example of how valuable it is to preserve fossils and material for future research.

"This is a very nice article that shows how historical collections can gain new relevance in modern times," says Roberts.

It is worth noting that the specimen was almost lost due to relocation and flooding, she says.

"This highlights the importance of proper preservation and documentation of scientific collections. Fortunately, it was rediscovered, and now it provides new insights into the history of plesiosaurs, especially in the Arctic regions," she says.

Survived a time period shift

Roberts agrees with Delsett and the other researchers that the specimen belongs to the genus Colymbosaurus, one of the largest long-necked plesiosaurs from the Late Jurassic (around 150 million years ago).

"What makes this find particularly exciting is that the specimen is younger than previously known Colymbosaurus finds," she says.

The Ellesmere specimen dates from the Early Cretaceous (approximately 140-135 million years ago).

"This clearly shows that this genus survived the transition between the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods – a time when many other long-necked plesiosaurs disappeared," says Roberts.

"Why this particular genus survived remains unclear. Perhaps it’s simply because fossils from other species have yet to be discovered," she says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Delsett et al. Boreal waterways: An Early Cretaceous plesiosaur from Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canadian Arctic and its palaeobiogeography, Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 2024. DOI: 10.4202/app.01148.2024

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.