Chance discovery provided fantastic images of ancient lizard fossils

Researcher Victoria Engelschiøn was simply searching for bivalvia fossils in ancient rocks from Svalbard when something completely unexpected appeared in the images.

On Edgeøya, east of Spitsbergen, ancient life has been completely flattened.

It is common for fossils of lizards and dinosaurs to be compressed when preserved under layers upon layers of rock.

However, these fossils take the process to the extreme.

“They are so flat! Some of them measure only a few millimeteres,” says Victoria S. Engelschiøn from the Norwegian Center for Paleontology at the Natural History Museum in Oslo.

The area on Edgeøya contains heaps of fossils, including those of ichthyosaurs – a type of predatory reptile that ruled the seas for over 150 million years, while dinosaurs walked the land areas. The rocks that now lie on land were once the seabed of a shallow bay.

But the fossils scattered here can be difficult to examine because they are so tightly packed.

Indeed, the shape of the bones is crucial for learning more about the creature that once lived, but it can be almost impossible to extract these fossils from the rock without damaging them.

That is why Engelschiøn's discovery is so valuable.

Searching for bivalvia

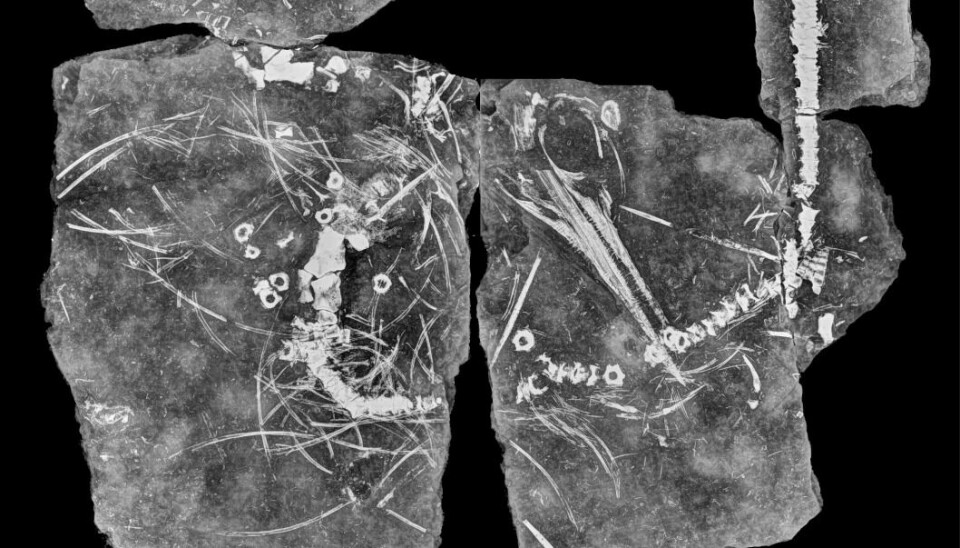

Engelschiøn simply placed a piece of old seabed into a CT scanner, which takes three-dimensional X-ray images.

“I actually did it to look for bivalvia that lived in the mud,” she says.

But when the researcher obtained the CT images, something else caught her attention:

Lizard bones, which stood out in incredible contrast to the surrounding rock.

These were just random bones lying in the rock. What was interesting, however, was how remarkably clear they appeared in the X-ray images.

Could this also apply to other fossils from the area?

Lizard skull

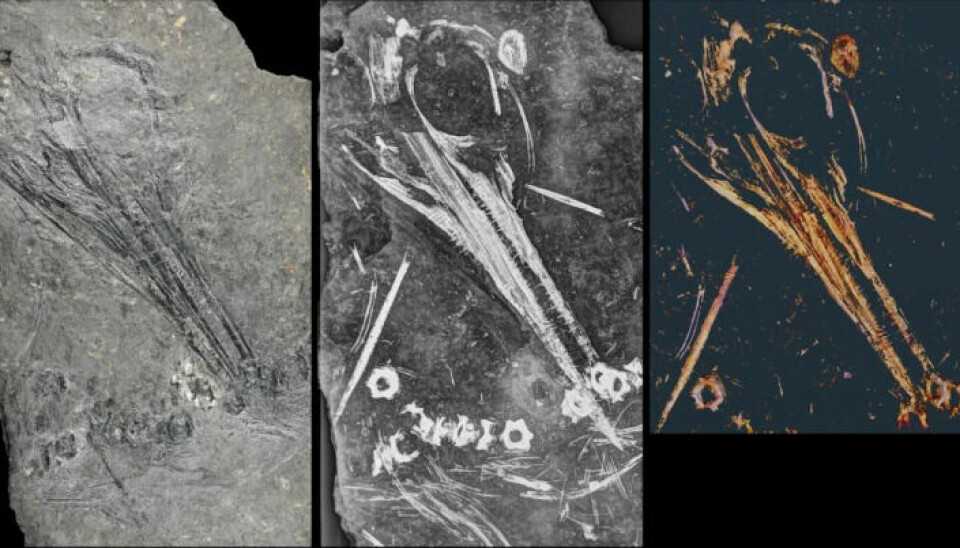

Using X-ray imaging to study fossils is still quite new, and no one had previously attempted this technique on Svalbard’s lizards from this area, according to Engelschiøn.

“My colleague, Aubrey Roberts, came up with a suggestion: What about putting an entire lizard in the CT scanner?” she says.

As intended, it was done.

The researchers selected a well-preserved fossil of an ichthyosaur that lived in the area around 240 million years ago.

Ichthyosaurs were enormous, but this fossil had already been divided into smaller parts. This was necessary because the researchers had to carry the pieces on their backs out of the excavation area.

However, the parts were too large to fit into the CT scanner at the Natural History Museum.

“But the Museum of Cultural History has an X-ray machine large enough to capture images of the pieces, and we were able to borrow it,” Engelschiøn says.

Exceptional contrasts

The results, presented today in the scientific journal PLOS One, lived up to expectations.

Bones, teeth, and skull emerged from the rock in clear contrast. But why were they so remarkably distinct?

Further investigations showed that the bone tissue that once existed in the bones had been completely replaced by the mineral barite, a mineral consisting of barium and sulphur. The researchers do not know exactly why this happened.

Perhaps volcanic activity caused hot fluids to rise up through the layers of rock and dissolve the bones, while barium and sulphur in the fluid crystallised into barite in the resulting cavities?

Regardless of the cause, barite is the explanation for the excellent images.

This mineral shows up very well on X-rays. Barite – and the substance barium – are known to create high contrasts in X-ray images.

“Barium is actually used in the contrast fluid given to patients undergoing CT scans of the body,” Engelschiøn says.

Discovered species for the first time on Svalbard

Just as CT images provide doctors with useful images of the inside of the body, X-ray images of the Svalbard fossil have provided researchers with new knowledge about ichthyosaurs.

Although this fossil had already been treated with special techniques to enhance the visibility of the bones, previously unseen details emerged.

“For example, we could see the roots of the teeth, which is important for determining the species,” Engelschiøn says.

This made it possible to determine that the fossil is likely of the species Phalarodon atavus.

This species has previously been found in China and Germany, but this is the first discovery on Svalbard. This could provide new insights into how these animals lived.

Moved extensively along the coast

“At that time, the land masses of the world were united in the supercontinent Pangea,” Engelschiøn says.

The areas that today lie on Svalbard were a shallow sea bay in northern Pangea, while present-day China and Germany were much farther south, near the equator.

“This means that this species moved along the coast. They were clearly capable of swimming long distances,” she says.

For now, we can only speculate on what the animals did in different ocean areas, whether they migrated back and forth between regions or had more settled habitats in different places.

The next step is to examine more of the ichthyosaurs from Svalbard and ichthyosaurs from other parts of the world, Engelschiøn says.

By comparing them, researchers may be able to learn even more about how ichthyosaurs lived and spread throughout the world.

“Perhaps this can provide us with more details in the broader story of ichthyosaurs,” she says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Engelschiøn et al. Exceptional X-Ray contrast: radiography imaging of a Middle Triassic myxosaurid from Svalbard, PLOS ONE, May 2023. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285939