Privatised rental market inflates costs

Renting a flat in Oslo’s privatised real estate market is more expensive than in Stockholm and Copenhagen, where costs and rents are regulated. The two different Scandinavian systems each have their advantages and drawbacks.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The Nordic countries are fairly well known for their social democratic welfare states. But these countries differ considerably in one major area of the economy: the real estate rentals market.

Norway and its capital Oslo have a nearly exclusively privatised and deregulated rentals market, while Swedish and Danish state and municipal authorities keep a tight rein on their markets by regulating prices and access.

A large share of rental flats in the other Nordic capital cities are publically owned. These represent a housing option for people with average or low incomes who cannot, or do not, wish to buy a flat to take advantage of the rise in real estate values – when they come – or risk taking a loss when bubbles burst.

It’s not easy to say whether regulation or a deregulated market is the most suited for stimulating construction or reducing social inequality.

One thing is certain, however. Price regulations keep rental prices down.

Less public housing available, higher prices

The capital city regions of Denmark, Sweden and Norway are comparable in size. They all have about a half million residents in the central city and about a million in nearby suburbs and towns.

The average monthly rent for a common family flat – a rent regulated, publically owned apartment – with a floor space of 78 m² in Copenhagen in 2012 was € 890. Statistics Sweden estimates the average rental price of a flat in Stockholm in 2012 at SEK € 694, but doesn’t mention the size.

Comparable figures from a rental market survey covering Oslo, and its neighbouring municipality Bærum, put the price for such a flat in the third quarter of 2012 at € 1,223.

The Danish and Swedish public flats represent more than 20 percent of the countries’ total housing units. In Norway, public or social housing is reserved for the demonstrably needy and represents only four percent of the total housing mass.

Regulations better for renters

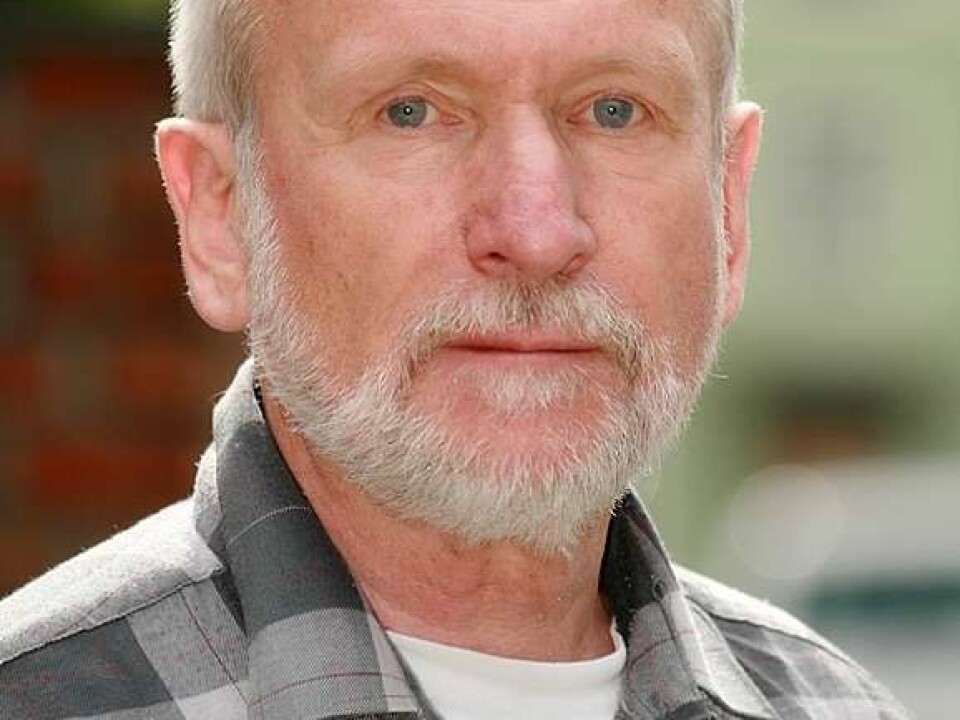

“People seeking housing in Stockholm and Copenhagen’s rental markets are better protected and the market is more controlled. This is the general difference among these rental markets,” says Erling Annaniassen, a researcher at Norwegian Social Research (NOVA).

Annaniassen authored a chapter on Norway in a book comparing the Nordic housing policies.

“For a tenant it’s best to be in a market that is more regulated than Norway’s. He or she is less vulnerable to overpricing and real estate sharks. In Norway it’s an advantage to own your own residence. This has formed the basis for the entire system and consequently it’s less favourable to rent,” says Annaniassen.

About a fifth of Norwegian residences are leased.

“The great majority of people in Norway with little means, apart from the few who qualify for municipal housing, currently live in privately owned rentals. This market determines prices, and can lead to overpricing, especially in Oslo, which has a housing shortage,” asserts Annaniassen.

Danish policies keep prices down

Rikke Skovgaard Nielsen is a researcher at the Danish Building Research Institute at Aalborg University. She stresses that Denmark’s rental policy definitely has an impact on price levels.

“In Denmark the private rental market is linked to pricing in the municipal public system. So when you rent from a private owner the prices depend on the rents in the general sector for a comparable home,” she says.

“This keeps prices down because the public rental rates are calculated from the costs of construction and maintenance of the building. If you have pay too dearly to private owners, you can complain to a rental appeals board and get the rate lowered. This has been done successfully in several cases the past few years.”

Hard to link privatisation with construction

Prices are just one aspect of the housing market. Another is construction. All the major Nordic cities have housing shortages. Can deregulation of the market encourage entrepreneurs build more housing? Or, contrarily, would a stronger public grip on the market stimulate more construction activity?

The answer, according to a Swedish research report from 2009 comparing housing policies in Amsterdam, Helsinki, Copenhagen and Oslo, is ambiguous:

“The same problems crop up in the different alternatives, and for that reason it’s hard to propose any single solution to the housing problems,” Anders Lindbom, professor of political science at Uppsala University, writes in the report.

He says that construction of new housing in Oslo was at a record-high in the early 2000s. Upwards of 4,000 new housing units were built in 2005. But those interviewed for the study were more likely to attribute this boom to a lag from the 1990s, when construction was really slow, rather than to stimulation from the private market.

The rental market in Helsinki was deregulated in 2005, but Lindbom found no indications of this changing the pace of housing construction one way or another.

Lindbom's interview subjects, who were public and private decision-makers at several levels, claimed that lower costs linked to streamlined building techniques and a reduction in bureaucratic paperwork were the key factors for decisions whether to build.

No waiting list problems in Norway

It’s easier to find cheaper housing in Stockholm and Copenhagen than in Oslo because in the first two market prices are regulated.

On the other hand, it’s harder for a Dane who has saved the downpayment to move to a flat in the more attractive areas. There are waiting lists for those who have money, just like for anyone else.

These queues spawn other prospective problems that are found less frequently in the free Norwegian market:

“The units are financially available, but there’s so much demand that it can be hard to procure a private home. This can be a disadvantage for those who are socially vulnerable. When private owners have so many prospective tenants to choose amongst, immigrants or others who are not well off can be rejected,” says Rikke Skovgaard Nielsen.

“Some private flats never come onto the market. Instead they are leased through networks. This makes accessibility for vulnerable groups even more difficult.”

However, she adds that access to public housing, aside from central Copenhagen, is ample. As a result, very few immigrants in Denmark actually try to enter the private rental market.

Sweden becoming more like Norway

Does the regulation of the rental market segregate the poor or immigrants in particular city districts? Or on the contrary, is it deregulation that leads to wider socio-economic and ethnic gaps?

Susanne Søholt of the Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research (NIBR) has studied ethnic divisions in the housing market. She thinks the Danish system has advantages that Norway could learn from.

The public rental system has universal allocation rules. This means that ethnicity or income are less likely to influence the chance of finding a place to live.

“Our investigations show that immigrants experience being on an equal footing with Danes. They can get a home and have an opportunity to move to larger units or to other neighbourhoods if necessary,” says Søholt.

“This is the way it has been in Sweden and Finland too. But the times seem to be changing. In Sweden there is pressure to sell public holdings, so municipal housing becomes privately owned. This, combined with an influx of residents to Stockholm, makes it harder to get municipal flats and harder to trade up for something better.”

Same problem for minorities in several systems

A study that Søholt published with Lena Magnusson Turner of NOVA and Hans Skifter Andersen of the Danish Building Research Institute shows that all these systems are beleaguered with problems relating to social class.

They write in the Journal of Housing Policy that immigrants are more often cramped for living space and are economically poorer than the rest of the population in Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Norway.

Crowding is worst in Norway and least evident in Denmark.

The problem is linked to different causes. Norway has a general shortage of rental flats – units are often small and prices are very high for all types of dwellings.

In Denmark, rental and price controls impact the private rental market and limit opportunities for immigrants. The municipal rental market provides better opportunities but forces immigrants to live in specific areas where the housing is found.

No stigma attached to Swedish municipal housing

Social geographer Lena Magnusson Turner was formerly affiliated with Uppsala University in Sweden. She studied the real estate market there and says Sweden differs drastically from Norway.

“Norwegians generally anticipate constantly rising prices, it’s a given assumption, whereas Swedes and Danes know prices are apt to rise and fall. Sometimes prices plummet and there are still a lot of Swedish families who are deep in debt because of the last collapse,” says Turner.

She says lots of Swedes prefer to rent.

“This is particularly true for people in a dynamic phase of their lives, up to the age of about 35. They are often students, maybe cohabitating for a while and unsure about where they will be getting jobs. That makes buying property a risky venture,” says the researcher.

Turner stresses that the Swedish rental market is not free of dilemmas. Social disparities exist and in some districts poverty and social exclusion squelch opportunities – despite rental market regulations.

“But generally speaking, the Swedish public rental policy is truly beneficial. Living in a municipal apartment in Norway is a social stigma. You are an outsider or a loser. It’s not like that in Sweden. Renting in a municipal flat is totally okay,” says Turner.

----------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling